Russia's balancing act in North Africa

Last week, Russian Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev went to North Africa on official visits to Algeria and Morocco — two days in each country. In Algeria, Medvedev was privileged to meet with President Abdelaziz Bouteflika, prompting the pan-African weekly news magazine Jeune Afrique to remark acidly that French President Emmanuel Macron and German Chancellor Angela Merkel are still on the waiting list to see Bouteflika.

Last week, Russian Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev went to North Africa on official visits to Algeria and Morocco — two days in each country. In Algeria, Medvedev was privileged to meet with President Abdelaziz Bouteflika, prompting the pan-African weekly news magazine Jeune Afrique to remark acidly that French President Emmanuel Macron and German Chancellor Angela Merkel are still on the waiting list to see Bouteflika.

In Morocco, Medvedev was conferred an honorary doctorate from Mohammed V University. Speaking of prospects for the bilateral relationship between Russia and Morocco, Medvedev quoted the movie "Casablanca," saying, “I think this is the beginning of a beautiful friendship.”

He added, “The friendship between Russia and Morocco began long ago, and there is every reason to believe that it will only grow stronger and develop for the benefit of the peoples of both countries."

Should the Medvedev tour be seen as a manifestation of Russia’s new strategy? Its approach until recently barely extended over to the Arab world's “Far West." Is it a symptom of some internal changes within the Russian political apparatus, given that Medvedev has been largely preoccupied with domestic affairs, whereas foreign policy and especially the Middle East were very much in the domain of Russian President Vladimir Putin?

Neither of those scenarios appears to be the case.

Medvedev's visit didn’t come out of the blue. A Russian diplomat with knowledge of the visit's details told Al-Monitor both Algeria and Morocco had been put on the prime minister’s travel schedule at least six months ago, with intense preparations across several ministries ever since.

He has long been engaged in Algeria. In 2001, Russia and Algeria signed an agreement on a strategic partnership. For the next 16 years, economics and — to a larger extent — military-technical cooperation have come to dominate the bilateral agenda. By 2016, the annual trade turnover between the two countries, according to Medvedev, amounted to $4 billion — the lion’s share of which came from Russian weaponry. More than 90% of Algerian arms are exported from Russia. Algeria's annual exports to Russia are limited to several hundred million dollars.

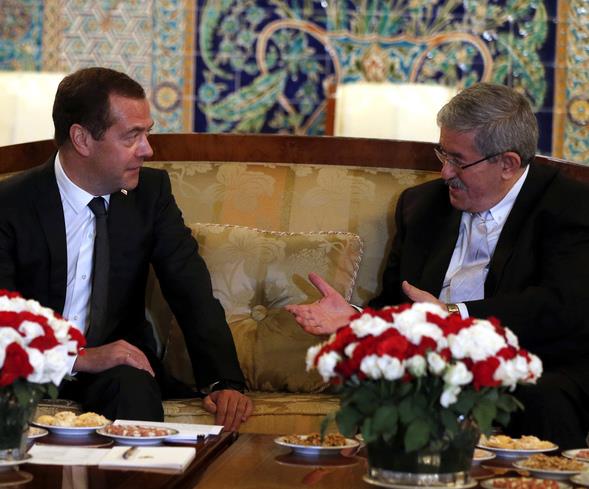

In an interesting diplomatic twist, this trip marked a reunion of sorts between Medvedev and an old confrere. In 2010, when Medvedev was Russia's president, he met with Ahmed Ouyahia, who was in his third term as Algeria's prime minister. Just two months ago, Ouyahia was unexpectedly tapped to return to the position, enabling him to resume working with Medvedev.

Among the dozen documents signed during Medvedev's recent visit, the most notable included those on oil, gas and nuclear power development. Some sources reported the two parties might have discussed Algeria's potential purchase of Russian S-400 missile systems, and Su-32 and Su-34 fighter bombers, as well as the potential for Russian companies to manufacture trucks and bulldozers in Algeria.

As is often the case with senior Russian officials’ tours to the region, Medvedev’s trip to Algeria was combined with his visit to Morocco. Not only does the strategy make sense for logistical reasons, it's also designed not to offend either neighbor.

As with Algeria, Medvedev’s economic dealings with Morocco heavily dominated the agenda. Although the Russian-Moroccan trade turnover of $2.5 billion is much lower than that between Russia and Algeria, it has a different structure and is on a constant rise. With Algeria, the prevalent component is military-technical cooperation, but Russia’s trade with Morocco centers on agriculture, with a number of small- and medium-sized businesses being important players, which nurtures deeper bilateral ties. Also, trade relations between Russia and Morocco seem much more balanced than those between Russia and Algeria.

In Morocco, Medvedev signed a dozen accords, mainly in agriculture, but the parties also reportedly reached key agreements for Russia to supply liquefied natural gas (LNG) to Morocco. Last month, Russian Energy Minister Alexander Novak was also in Morocco, where he said that the construction of an LNG regasification terminal was underway and that the two states discussed gas deliveries by the Russian companies Gazprom and Novatek.

What can be called the “pedantic parallelism” that Moscow pursues in constructing relations with Algeria and Morocco likely indicates Russia’s unwillingness to dive into complex regional games in the Maghreb, and its aspiration to limit, by and large, its relations to an economic agenda.

Another indicator of Russia’s balancing act in the region is Moscow’s neutrality on the Western Sahara issue. Delegations of the Algerian-backed Polisario Front — the Sahrawi people of Western Sahara's movement for independence from Morocco — visit Moscow every spring, hosted by the Russian Foreign Ministry and the Federation Council (Russia’s Senate). Russian officials have always been careful not to make any anti-Moroccan statements. Algeria has accommodated Western Sahara refugees in camps for decades.

The “parallelism,” however, should not be misconstrued. Russia is perceived differently in Algeria and Morocco and occupies a different place on each one's list of foreign policy priorities.

For Algeria, Moscow has always been an important partner. From 1954-1962, the Soviet Union actively supported the country’s national liberation movement and the National Liberation Front, a socialist political party. Soviet universities educated future leaders of the Algerian military and a large part of the national intelligentsia. And when the Soviet Union began allowing cybernetics into its own academic curriculum, Algerians were among the first lecturers the Soviet leadership invited.

Today, the Museum of Modern Art of Algiers hosts a collection of both Soviet and Algerian artists who used to live in Russia. The “special relationship” between the two countries survived the downturns of the 1980s — against the backdrop of the crisis of socialism — and the economically rough 1990s. Moreover, the very nature of Algerian statehood makes its leadership refrain from an excessive rapprochement with Europe and keep an emphasis on its independence from its former parent state, France.

It’s a totally different case with Morocco. Its traditional association and cooperation with the EU, as well as the political familiarity between the Moroccan and Saudi monarchies, are all natural constraints to a more intimate alignment with Russia.

This background implies that no matter how skillful Russia is in its parallelism diplomacy, should Moscow have to increase its political involvement in the region it will need to further diversify its contacts with both countries. In Algeria's case, Russia is likely to actively develop humanitarian ties, to boost existing military-political interaction. With Morocco, Russia would have to place more emphasis on promoting economic ties to compensate for the lack of vibrant joint political formats.

That, however, is a matter for the future. So far, Medvedev's visits have demonstrated that Moscow is not forging a new Russian strategy in North Africa, but rather is naturally seeking to capitalize on its success in Syria and position itself as a main security supplier to the region.

Article published in Al Monitor: http://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2017/10/russia-medvedev-visit-algeria-morocco-diplomacy.html

Photo credit: Sputnik/Dmitry Astakhov

Russia keeping a close eye on Algeria

The news about establishing safe zones in Syria, the leadership reshuffle in Palestine’s Hamas and the Abu Dhabi meeting of two Libyan leaders, Khalifa Hifter and Fayez al-Sarraj, stole the limelight from the Algerian parliamentary elections held May 4, making them seem a more or less mundane event unworthy of much media scrutiny.

The news about establishing safe zones in Syria, the leadership reshuffle in Palestine’s Hamas and the Abu Dhabi meeting of two Libyan leaders, Khalifa Hifter and Fayez al-Sarraj, stole the limelight from the Algerian parliamentary elections held May 4, making them seem a more or less mundane event unworthy of much media scrutiny.

True, one can confidently say on seeing the unchanged post-election landscape two weeks later that there was hardly anything sensational about the campaign. Algerian President Abdelaziz Bouteflika’s National Liberation Front (FLN) and the National Rally for Democracy (RND), the two major parties in the presidential coalition, retained their majority; moderate Islamists’ share of seats remained almost intact, and other traditional competitors predictably lagged far behind.

Still, Moscow keeps Algerian developments on its radar screen — especially in light of what is happening in neighboring countries.

For Russia, Algeria has been a vital Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region partner for technical-military cooperation dating back to the 1960s, when the Soviets helped Algeria equip its newly created army. Algeria has been a major Russian market for wheat and metal, while Russian energy companies have been developing Algeria’s hydrocarbon mining and building pipelines since at least the mid-2000s.

So Algeria’s election held interest for Moscow and revealed some trends.

One of these trends was the low turnout, which was just above 37% (unless overseas constituencies are included, then the figure was 38.25%). The Algerian government’s attempts to galvanize voters into casting ballots did not bear much fruit, even when Prime Minister Abdelmalek Sellal promoted the election as he toured the country.

Citizens’ disillusionment with the country’s economic situation has simmered for years. In 2007, as many as 14.4% (965,064) of the ballots were disqualified, with the figure increasing to 18.2% (1.7 million) in 2012.

Earlier this year, falling oil and gas prices triggered an economic crisis, driving people to the streets in protest. The economy could have produced a disastrous result at the polls. But Robert Parks, a seasoned expert on Algeria, was right when he claimed Algeria has not yet faced a crisis of the presidential regime. A decline in electoral participation has been characteristic of recent regional campaigns as well as national ones.

However, the number of disqualified ballots this year — more than 2 million (24.47%) — can be interpreted as a sign of some crisis, even if it is not in full swing yet. Some people feel sidelined and excluded from participation and abstain from voting. Some people go through the process of voting but intentionally deface or otherwise invalidate their own ballots, demonstrating mistrust of the current government and the opposition alike.

Many Russian experts on the MENA region believe the decision of all the major parties to join the race — which distinguishes the 2017 electoral campaign from the one in 2012 — reveals the parties’ complete integration into the highly consolidated political elite and desire to work within the constitutional framework.

To Russians, the problems the Algerian elections brought to light are reminiscent of the difficulties Russian society experienced during the September elections. Deputies of the State Duma, Russia’s lower legislative house, enjoyed the support of all the parties, which went almost unnoticed by ordinary citizens. Voter turnout was 13% lower than in 2011.

Both cases prove that the political establishment has completely divorced itself from the concerns of ordinary people, with the latter unable to find effective representation and disillusioned with all political ideologies.

France and the United States have witnessed similar situations. France’s recent presidential runoff saw a fourfold increase in blank and spoiled ballots over the first round. US President Donald Trump’s electoral success was widely interpreted as a rebellion against political elitists.

Thus, the developments can be referred to as part of a global trend. In fact, nobody knows what most of the world’s population wants. Nor do people have a clear vision of their own aspirations. Consequently, the Algerian parliament represents the interests of the estimated 6.4 million people who actually voted, out of more than 41 million citizens. Central governments face a clear credibility gap all across the world.

Waning support for the FLN and the RND’s growing popularity deserve special attention. As Russian pundits believe, this trend testifies to the strength of former Prime Minister Ahmed Ouyahia, one of the RND’s founders and the party’s current leader. Ouyahia is considered one of the most likely candidates for the presidency, backed by his considerable government experience and credibility among most establishment forces, his moderate but pro-national stance and a fluent command of Tamazight (which was recognized last year as an official language of the country).

At the same time, Algeria’s political system allows little scope for accurate predictions. Regardless of further developments and Ouyahia’s role, it is evident that any government in power will have to press ahead with some unpopular reforms, which, in their turn, will require confidence-building measures among the people. Making progress in foreign policy issues would help with that greatly, especially regarding Western Sahara, the Algerian-Moroccan relationship and Libyan issues.

Algeria shelters an estimated 165,000 Sahrawi refugees, the indigenous people of Western Sahara — a disputed territory claimed by Morocco.

Morocco left the African Union more than three decades ago when the union recognized Western Sahara’s independence. Morocco recently rejoined the AU, which Algeria takes as a sign that Morocco also will acknowledge Western Sahara — but more likely it will only mean Morocco will have a louder voice on the continent and will perhaps gain better cooperation from other countries. The Moroccan royal family’s strong international positions leave little room for fence-mending on Algeria’s terms.

Therefore, working on the Libyan issues looks to be the most logical play.

In this context, the May meeting of representatives of Libya’s neighboring countries — which brought together the foreign ministers of Algeria, Tunisia and Egypt — comes into sharp focus, as does a subsequent security-related conversation among Sarraj, Sellal and Abdelkader Messahel, Algeria’s minister for Maghreb, African and Arab affairs.

Nevertheless, when Algeria’s activity is appreciated by Tripoli, it raises the ire of the rival government in Tobruk, which backs the “renegade general” Hifter. This situation is illustrated by the House of Representatives meeting during Messahel’s recent trip to southern Libya, where he was met with howls of outrage.

The response seems to have been conditional upon the differences between regional stakeholders — pro-Qatar Algeria and largely pro-Saudi Egypt — as well as the split state of affairs in Libya. Russia, backed by its partners and maintaining close relations with Hifter’s Libyan National Army and Algeria, could help soften Tobruk’s and Algeria’s stances toward each other, which would benefit all the North African countries.

Initially published by Al Monitor: http://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2017/05/russia-monitor-algeria-north-africa-economy.html#ixzz4hiGfE5NE

ISIS takes its fight to Russia’s backyard

More and more terrorist groups swear allegiance to the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) and the international attempts to bring down ISIS seem in vain.

More and more terrorist groups swear allegiance to the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) and the international attempts to bring down ISIS seem in vain.

The strongest extremist organization gains the terrain, both on the ground of Syria and Iraq and in the minds of people far from the Syrian and Iraqi borders. ISIS challenges the Security Services all over the world, as the way it spreads is extremely difficult to be cut and controlled.

ISIS spreads primarily through the Internet, using it as a sophisticated instrument of propaganda, recruiting and expanding, along with personal contacts of its recruiters. Spreading over the net, they create cells as metastases, far from the Syrian and Iraqi borders – in Nigeria, in Libya, in Yemen, in Afghanistan, in Algeria, in Tunisia and others. The list is already long and is becoming longer.

The alarming message has come from a Russian senior security official after a session of the SCO’s regional anti-terror body, saying that some warlords of the prohibited Emirate of Caucasus have pledged their allegiance to ISIS. This trend challenges not only Russia, over 1700 citizens of which have joined ISIS, and who fight in Syria and Iraq (this figure is an estimate, the real numbers could be higher still), but for the whole Caucasus region and the neighbouring countries.

To read the whole article: http://english.alarabiya.net/en/views/news/middle-east/2015/04/14/ISIS-takes-its-fight-to-Russia-s-backyard.html

The MidEast World: best of 2014

IMESClub presents you the 40-pages-length issue of "The MidEast Journal" – collection of the 2014 brilliant pieces of our eminent members.

IMESClub presents you the 40-pages-length issue of "The MidEast Journal" – collection of the 2014 brilliant pieces of our eminent members.

The issue besides other pieces includes:

❖The IMESClub interview of the year: Interview with Bakhtiar Amin, Chairman of the Board of Directors of the Foundation for Future, Former Human Rights Minister of Iraq. The interview was devoted to the Iraq, its fate, on the US role and etc.

❖Brilliant dossier on Russia-Algeria relations by Mansouria Mokhefi, Special Advisor on the Maghreb and the Middle East at Ifri, Research Associate at ECFR.

❖Another one interesting dossier on Russia-Iran relations by Lana Ravandi-Fadai

The issue is available in PDF in one click.

▲(click the pic).

Thinking Over the Arab Spring (Global University Summit-2014 speech)

This April in the framework of Global University Summit 2014 that took place in MGIMO-University in a friendly and effective partnership with MGIMO and the Institute of Oriental Studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences IMESClub held its round-table "Global Efforts to Settle the Situation in the Middle East. Capabilities of the Deauville Partnership".

This April in the framework of Global University Summit 2014 that took place in MGIMO-University in a friendly and effective partnership with MGIMO and the Institute of Oriental Studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences IMESClub held its round-table "Global Efforts to Settle the Situation in the Middle East. Capabilities of the Deauville Partnership".

And today we're publishing the text of the brilliant speech delivered by one of three key speakers of that meeting – Mansouria Mokhefi.

Introduction

Since 2011 and the fall of Arab dictators in Tunisia, Egypt, Libya and Yemen, scholars and policymakers have sought to assess the importance of the popular protests for democratization, political stability, and geo-strategy across the Arab world. Three years later, the hopes that the uprisings would bring freedom and equality while producing stable democracies have largely gone unrealized. The post Arab spring environment, marked by political, economical and social dysfunctions as well as by internal conflicts and regional wars is more fragile, complex, volatile and dangerous than it has ever been.

Not only are an unprecedented number of Arab countries in the midst of one kind or another of large-scale armed conflicts, but new types of armed non-state actors are also waging war with local terrorist groups rising in many parts of the region. The rise of militant forces, as the result of a total failure of governance as well as a consequence of the culmination of decades of Arab resentment towards Western domination, has already shifted regional and international alliances and is about to redraw the map of the Middle East.

When assessing the so-called Arab Spring revolutions, one should not forget that the uprisings overthrew dictators but they did not overturn the prevailing political and social order: the political structures have remained unchanged despite the adopted democratic elections process and, aggravated by economic and social frustrations, and reinforced by local and regional insecurity threats, authoritarian ruling is still the norm.

One can only assess that faltering economies (1) and the rise of violence (2) are defining the new environment in an unprecedented fashion and continue to pose serious security threats (3) that are affecting the regional balance of powers (4).

1. Faltering economies

Economic liberalization taking place in Arab countries over the last three decades has resulted in greater poverty, rising income inequality and alarming rates of youth unemployment. Moreover, the region’s already stagnant economic situation has dramatically worsened in the countries that have weathered the Arab uprisings: new governments not only failed to appreciate the economic roots of the revolutions but have also been incapable of addressing the major problems of rife corruption and rooted cronyism that plague their countries. None of them has put forward the much-needed economic reforms likely to address the popular grievances or reduce the societal pressures, and a viable alternative agenda has yet to be put forward. Thus, the faltering economies, aggravated by rising prices, low wages, widespread labor strikes and a structural unemployment crisis, are still the source of growing frustrations and social unrests. Loss in revenue from oil and a substantial decrease in tourism, as well as lack of foreign investments, have turned sluggish growth to a non-existent one while paralyzing the economies and ruining the countries. The Arab spring revolutions have also revealed and widened large and increasing inequalities. The lack of opportunities for the growing number of youth is a difficult handicap to which none of the concerned countries has a solution. Therefore, post revolution Tunisian governments have been confronted by a sharp economic downturn that has been feeding political tensions and uncertainties, while Egypt is on the path to social disaster with fundamental economic problems that the large Gulf States’ assistance cannot solve. Post Arab Spring leaders are doomed to ultimately confront the same demands - “bread, dignity, and social justice” - that deposed their predecessors.

2. The rise of violence

Arab nationalism, the powerful ideological discourse of the post independence period, has showed its limits and has given way to variants of Islamism resulting in numerous sectarian factions that are fighting each other. The post Arab Spring context has demonstrated how Arab nationalism had in fact been the product and domain of Arab elites and national intelligentsias, whereas Radical Islam and different forms of Salafism have been taking hold among the massive and poor under-classes, highlighting the major division between these societies.

Tensions between radical Islam on the one hand and mainstream moderate Islam on the other have polarized many countries; they have reached alarming levels in Tunisia, culminating in the assassination of two political leaders in 2013, and precipitating the retreat of Ennahda from the government without solving the issue of coexistence between the two streams.

Ravaged by gun violence and political chaos, Libya is in the midst of a civil war. In Yemen, no real political transition has been accomplished while the North Shiite rebellion continues and the US drone war against al-Qaeda has polarized the country in a dangerous fashion.

In Syria, the death toll has reached 200,000, with roughly a quarter of the country's population displaced and despite calls from countries such as Russia, Iran and Algeria to engage in a political solution based on dialogue and reconciliation, Western countries have been opposed and Assad is still in power. Meanwhile, Djihadist radicalization and foreign militarization have aggravated a conflict that has spilled over to Lebanese soil and empowered radical Sunni jihadists like those of the Islamic State of Iraq and Greater Syria (ISIS), an Al-Qaeda offshoot with greater means and ambitions than Bin Laden’s organization.

Tensions over the place and role of the Moslem Brotherhood in Egypt have divided the country, put an end to the democratic transition, and brought back the military dictatorship. Since the military takeover, violence against Egyptian police, security and military forces has sky rocketed.

Confrontations over the Syrian war between Iran and Saudi Arabia, each backing a different side, along with their ongoing competition for the Moslem leadership, have aggravated the Shia -Sunni sectarian tensions and continue to feed violent divisions throughout the region.

Violence has been on the rise against all minorities: Christians are on the verge of total exclusion from the Middle East. And violence against women has also been recorded everywhere: while the revolutions were expected to bring equality and freedom, not only have women’s rights not been acknowledged but they have deteriorated everywhere, with an unprecedented number of rapes and alarming physical attacks reported in Egypt, Tunisia, and Libya.

3. Destabilization and security threats

The chaotic situation following Moubarak’s fall, the return to a military regime and the subsequent violent crackdown on the Moslem Brotherhood, the most intense since the 1950s, have expanded a cycle of political violence that has increased many security challenges facing Egypt. In addition to the growing domestic instability, the country is facing a growing insurgent activity in the Sinai where terrorist groups such as Ansar Beit al-Maqdis have been regularly attacking Egyptian security forces and threatening gas pipelines. The fight against these groups and their attacks has compelled the Egyptian Army into a new cooperation with Israel, but the attacks unabated.

The conflict in Syria has drawn Djihadists from all over the world. Their actions rare destabilizing the entire region with increasing threats on Jordan and Lebanon, the latter of which has already been drawn (through Hizbollah since the beginning of the uprising) into waging war in Syria. The region’s risks of destabilization are also emphasized by the fact that many countries are facing the specter of partition: Libya, Iraq, Syria, and Yemen.

Fed by extremist violence, poor governance, and social tumult, the Maghreb countries, already in varying states of crisis, are facing rising insecurity challenges as well. Terror activities have been recorded across the region, even in Algeria (attack on In Amenas in January 2013), which has managed to avoid the Arab Spring’s contagious revolutions, and in Tunisia (south of the country), which has never experienced terror attacks from Al-Qaeda. Simply put, since 2011, the chaos that succeeded Gadhafi’s fall, with Libya becoming a sanctuary for Djihadists, has been seriously threatening every neighbor’s security and stability.  The porous borders have facilitated massive circulation of weapons and the uncontrolled movement of Djihadists who have been expanding their territories and broadening their targets. Libya’s uncontrolled borders have become proliferating free-trade zones for the trafficking of weapons into neighboring areas, posing serious threats to all neighbors. This situation has propelled Algeria to increase its control over the region and to intervene beyond the country’s borders, in Malian, Tunisian, and Libyan territories. Moreover, the growing instabilities in and around North Africa, along with the difficulties in controlling trans-border terrorism, have also raised concerns regarding the possibility of the situation in the Western Sahara breeding new terrorism with militant groups operating in the camps. United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon warned about the Sahrawis’ vulnerability in the Polisario-controlled refugee camps in southwest Algeria to recruitment by criminal and terrorist networks.

The porous borders have facilitated massive circulation of weapons and the uncontrolled movement of Djihadists who have been expanding their territories and broadening their targets. Libya’s uncontrolled borders have become proliferating free-trade zones for the trafficking of weapons into neighboring areas, posing serious threats to all neighbors. This situation has propelled Algeria to increase its control over the region and to intervene beyond the country’s borders, in Malian, Tunisian, and Libyan territories. Moreover, the growing instabilities in and around North Africa, along with the difficulties in controlling trans-border terrorism, have also raised concerns regarding the possibility of the situation in the Western Sahara breeding new terrorism with militant groups operating in the camps. United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon warned about the Sahrawis’ vulnerability in the Polisario-controlled refugee camps in southwest Algeria to recruitment by criminal and terrorist networks.

4. New environment, shifting alliances

The new geopolitical landscape born out the Arab Spring is the result of the major events that took place over the past three years and the challenging outcomes that the revolutions have imposed on the region. First, it is important to recall that, due to many different events and developments that took place over the previous decades, the most important and traditional Arab players have seen their voice and influence considerably reduced and even destroyed: Egypt after the peace treaty with Israel and its alignment with the US; Iraq after the US invasion and destruction of the country built by Saddam Hussein; Syria since its international isolation and the Arab spring.

As a result of the Arab uprisings and their consequences, the region has never been so divided. Divisions created and exacerbated by the Egyptian situation and the Syrian war have left an Arab League more divided and useless than ever. The rivalry between Saudi Arabia and Iran has never been so fierce and it has been fueling growing divisions within the Moslem world. Rifts within the GCC, whose members (Saudi Arabia, UAE and Kuwait) have been trying to isolate Qatar, are another aspect of the many divisions that characterize today’s Arab world. Backing Islamists in various countries, Qatar has seen the political vacuums in the Arab Spring states as an opportunity to spread its clout, but the Islamists’ failures in Egypt and Tunisia have toned down the Qataris efforts to become an influential regional player and Qatar’s determination to deploy an independent foreign policy has been reduced and marginalized by Saudi Arabia’ s political strategy and financial influence.

In the Maghreb, Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) and its affiliates, whose activities have spread inside Algeria and in the Sahel region, continue to pose considerable threats. The French intervention in Mali, Operation Serval, in January 2013 was a consequence of these attempts at destabilization and takeover. In addition, the dispute over the Western Sahara continues to simmer, hindering all cooperation between Algeria and Morocco, the two major stable countries in a region that has already experienced the increased expansion of Islamic extremism and Djihadist terrorism.

In this new context, it is noteworthy that, after having controlled the dynamics of the region’s politics for most of the 20th century and the first decade of the 21st, the Western world has seen its influence challenged and diminished. The Arab Spring accentuated the relative decline of Western influence throughout the region: after being the absolute arbiters of the political balance in the Arab world, and though they remain the most important players because of the military security they provide, Europe has lost its economic and financial power and the US has lost its moral authority. Following the wars in Iraq et Afghanistan, Western interventionism in the Libyan crisis and the ambiguous and ambivalent policy regarding the Syrian war have facilitated Russia’s prominent return to the region, where, as an unavoidable player in Syria and a crucial partner in Egypt, it has been challenging Western decisions and orientations. In addition to Russia, new players are entering the field, with Arab countries turning towards new partnerships with China, India, Brazil and Turkey. While inter-Arab cooperation remains insignificant and will remain so in such a divided context, the multiplication of new players constitutes another challenge to the traditional Western influence in a region that has not finished with major shifts and repositionings.

Conclusion

While it has been widely reported that the Arab Spring revolutions will bring democratic reforms and advancements, democracy has actually regressed everywhere and the region has experienced the resilience or return of autocratic regimes.

Besides Tunisia, which might be the only country to emerge as a democracy, though still a very fragile one, for everyone else, instead of democratic transitions, a diverse range of political systems is the most likely prospect. All hopes related to the Arab Spring ended in fact with the Syrian conflict and its disastrous consequences on the region. Everywhere, fragility, discord, and a lack of security have caused the multiplication of ungoverned spaces and the proliferation and reorganization of terrorists groups that appear to be more dangerous than Al Qaeda. For Western powers, the Arab Spring also marked the end of a total and exclusive influence. The United States and the EU have always been far more focused on economic cooperation and/or support, and far less on building democratic institutions or defending basic freedoms. Now that they are engaged in different wars aiming at suppressing or reducing the threats posed by Djihadism, they still need to focus on addressing the real issues of the support and financing (by other Sunni states) of the terrorists groups that have spread all over the region.

The United States and the EU are also, despite various other problems, compelled to cooperate with Moscow in the global war against Islamism. However, even though Western powers remain the most important players in the region, the growing disappointment of Arab public opinion toward the West and the persisting resentment about the West’s policies toward the Arab world are still omnipresent.

On another front, the rise of immigration stemming from the Arab Spring countries towards Europe, is not only feeding European public opinion’s growing fatigue, it is also reviving racist discourse and behavior.

Last, but not least, the specter of a Djihadist return to European countries that they left to join the Djihad in Syria or Iraq is a major concern for governments that still don’t know how to deal with this issue.

Analyse de la situation algérienne

Le président Bouteflika est le grand absent de la campagne électorale qui a commencé le 24 mars et s’est achevée le dimanche 13 avril, puisque celle-ci a été confiée par procuration à ses lieutenants, qui ont sillonné le pays pour lui, tenu des meetings à sa place et prononcé des discours en sa faveur sans que lui n’apparaisse jamais. Fatigué, affaibli et diminué par l’accident vasculaire cérébral d’avril 2013 qui a réduit ses facultés de langage et de mobilité, Bouteflika est un fantôme dans cette campagne mais aussi le grand favori du scrutin du 17 avril car peu d’Algériens doutent de la victoire annoncée et programmée de celui qui, à la tête du pays depuis 15 ans, a décidé de briguer un quatrième mandat.

Le président Bouteflika est le grand absent de la campagne électorale qui a commencé le 24 mars et s’est achevée le dimanche 13 avril, puisque celle-ci a été confiée par procuration à ses lieutenants, qui ont sillonné le pays pour lui, tenu des meetings à sa place et prononcé des discours en sa faveur sans que lui n’apparaisse jamais. Fatigué, affaibli et diminué par l’accident vasculaire cérébral d’avril 2013 qui a réduit ses facultés de langage et de mobilité, Bouteflika est un fantôme dans cette campagne mais aussi le grand favori du scrutin du 17 avril car peu d’Algériens doutent de la victoire annoncée et programmée de celui qui, à la tête du pays depuis 15 ans, a décidé de briguer un quatrième mandat.

Faute de proposer un nouveau programme, une vision nouvelle pour le pays, le président s’appuie sur les progrès, les avancées et les réalisations sous ses trois mandats. Quel est donc le bilan de Bouteflika ?

L’empreinte de Bouteflika sur l’histoire de l’Algérie indépendante

Rappelons d’abord que Bouteflika avait déjà marqué l'histoire de son pays quand, après avoir participé à la guerre de libération contre la puissance coloniale française, il était devenu ministre des Affaires étrangères du président Boumediene, un poste qu’il a occupé pendant plus de dix ans durant lesquels l’Algérie a acquis une réputation internationale depuis lors perdue et jamais retrouvée. Poids lourd de l’OPEP, leader du tiers monde, champion d’un nouvel ordre économique international, médiateur de conflits internationaux, l’Algérie portait une voix qui s’entendait et comptait, et le pays éprouve encore une profonde nostalgie pour cette période de gloire symbolisée par Bouteflika.

Après le décès de Boumediene, Bouteflika disparaît de la scène nationale et entame une traversée du désert (ou était-ce un exil doré ?) qui durera plus de 20 ans avant de réapparaître comme l’homme providentiel au cœur d’un pays ravagé par une guerre civile qui, en 10 ans de violences meurtrières, a fait plus de 100 000 victimes. En 1999, Bouteflika accède à la présidence d’un pays meurtri et profondément traumatisé et son objectif premier est de tenter de ramener le calme, d’encourager le retour à la paix et de réconcilier la nation avec elle-même. Il fait alors adopter par référendum et met en œuvre la « concorde civile », qui prévoit une amnistie partielle des islamistes ayant renoncé à la lutte armée et n'ayant pas de sang sur les mains. En 2005, il fait adopter la « Charte pour la paix et la réconciliation nationale », le cadre qui prévoie des indemnisations pour les familles de disparus et des aides pour celles des terroristes, et en 2006, il fait libérer près de 1 500 islamistes condamnés pour terrorisme, indiquant par là même qu’ils ne représentent plus aucun danger pour la paix et la stabilité du pays.

L’acharnement de Bouteflika à ne pas s’effacer après trois mandats successifs, à s’accrocher au pouvoir malgré son état de santé et à refuser une transition qui permettrait au pays de tourner la page sur cette phase de son histoire ne risque-t-il pas de ternir de manière irrémédiable l’image de l’homme providentiel qui a permis le retour effectif du calme et la reconquête de la paix en Algérie ? Bouteflika ne risque-t-il pas par son obstination de remettre en cause la place que son rôle depuis l’indépendance lui accorde dans l’histoire de son pays ?

Un bilan économique et social contrasté

À l’arrivée de Bouteflika à la tête du pays, celui-ci se libérait à peine de l'emprise du Fonds monétaire international et de la Banque mondiale, qui lui avaient imposé des mesures draconiennes. Mais, depuis le redressement des prix du pétrole en 2000, l'Algérie a engrangé des revenus considérables qui lui ont permis de rembourser sa dette, d’accumuler des réserves de change estimées en 2013 à 200 milliards de dollars et de s’engager dans des projets de construction et d’infrastructures estimés à plus de 500 milliards de dollars.

Grâce à cette manne financière, l’Algérie a réalisé plus d'infrastructures en 10 ans, entre 2003 et 2013, qu'en 40 ans, entre 1962 et 2002, Bouteflika ayant lancé un programme colossal pour chacun des trois mandats : un Plan de soutien à la relance (PSRE) de 6,9 milliards de dollars en 2001, un Plan complémentaire de soutien à la croissance (PCSC) de 155 milliards de dollars pour la période 2005-2009, puis un plan quinquennal 2010-2014 de 286 milliards de dollars, dont 130 milliards pour terminer les travaux du plan précédent. En 15 ans, le pouvoir a considérablement accru les dépenses, dépenses qui ont nourri et développé la corruption politique à tous les niveaux de l’État et de la société, provoquant des scandales qui sont tous remontés à la sphère du pouvoir, très près de l’environnement le plus proche du président.

Impressionnés par les réalisations économiques de leur pays,- l’Algérie dispose du PIB par habitant le plus élevé d’Afrique du Nord - les Algériens ont aussi vu leur PIB par habitant passer 2 500 euros en 1999 à 5 600 dollars en 2013, ils ont vu l’émergence d’une classe moyenne et la constitution d’une classe d’entrepreneurs, les nouveaux patrons de l’Algérie, millionnaires et milliardaires dont le poids politique commence à se faire sentir. Cependant, malgré l’amélioration du quotidien de millions d’Algériens, la pauvreté perdure, le chômage devenu structurel prive d’avenir des milliers de jeunes (on estime à 10 000 le nombre de jeunes qui tentent chaque année de quitter le pays illégalement pour rejoindre l’Europe) et l’agitation sociale est devenue une marque de la vie algérienne, avec des émeutes quasi quotidiennes, sporadiques mais néanmoins récurrentes et révélatrices de la profonde insatisfaction de la population. Si le pouvoir a réussi de manière ponctuelle à « acheter » une certaine paix sociale en procédant aux « saupoudrages » financiers qui ont jusqu’à présent réussi à démobiliser tout mouvement de contestation, il a aussi laissé proliférer les marchés informels qui ont d’abord masqué les taux de chômage (plus de 20% parmi les jeunes), puis ont pris le dessus sur la vie de économique nationale, dont ils dominent une grande partie, estimée selon certains à plus de 50%.

Certes, de très nombreux Algériens restent attachés à Bouteflika, qu’ils considèrent comme le père de la nation, et peu doutent de sa victoire finale ; mais cela ne les empêche pas d’être inquiets devant les redoutables défis que le pays doit relever, défis que la campagne électorale n’a pas abordés, le débat de cette campagne s’étant limité à l’état de santé du président candidat et à quelques promesses de « transition » visant à amender la constitution, soit pour une plus grande ouverture (promesse du candidat Benflis d’inclure dans le débat politique ceux des Islamistes qui en demeurent exclus) soit pour la création d’un poste de vice-président (engagement du clan présidentiel). Les défis auxquels le pays est confronté et que tout gouvernement devra affronter sont restés en suspens : ni les troubles qui agitent régulièrement la Kabylie ni les affrontements qui déchirent le Mzab depuis des mois n’ont été discutés; ni l’épuisement des réserves d’hydrocarbures, ni ses conséquences sur une économie tributaire de ce secteur qui représente 40% du PIB, 70% des recettes fiscales et 97% des recettes d’exportations, n’ont été abordés ; ni le fléau de la corruption, ni les scandales qui lui sont liés et les détournements de sommes colossales n’ont été discutés ; ni la situation politique régionale ni l’insécurité aux frontières sud du pays n’ont été analysées. Cependant, les Algériens savent que malgré des avances remarquables, l’économie nationale reste plombée par des lourdeurs bureaucratiques handicapantes, un chômage structurel et un secteur public tentaculaire, une économie informelle envahissante et une corruption généralisée ; ils savent aussi que dans un tel contexte, les changements nécessaires ne sauraient se limiter aux mesures préconisées par les candidats mais nécessitent un changement du système dans son intégralité et un renouvellement de génération.

Les relations Algérie-Russie

Bouteflika a permis à l’Algérie de sortir de l’isolement dans lequel la guerre civile l’avait plongée ; dépassant la relation « privilégiée » avec la France et celle traditionnelle avec les pays d’Europe, Bouteflika a entrepris de diversifier les relations diplomatiques et commerciales de l’Algérie en se tournant vers de nouveaux partenaires et en créant de nouveaux liens.

Si l’Algérie n’a pas retrouvé encore la place importante et la voix forte qu’elle avait longtemps eues en Afrique, elle s’est employée à renforcer les relations avec les États-Unis et s’est tournée vers les grandes puissances du XXIe siècle en développant de nouveaux liens avec la Chine, l’Inde, la Corée du Sud, le Brésil et la Russie.

Les relations russo-algériennes se sont nouées pendant les années de la guerre de l'Indépendance (1954–1962) lorsque l’URSS a apporté son appui politique au Front de Libération Nationale (FLN) et son soutien matériel à l’Armée de libération nationale (ALN). La position de l’URSS a été déterminante dans la conclusion de la guerre car elle a poussé les puissances occidentales à faire pression sur la France pour mettre un terme à un conflit en passe de devenir un autre foyer de tensions dans la guerre froide qui divisait le monde.

Son indépendance acquise, l’Algérie s’est alignée sur Moscou et a adopté le modèle de développement socialiste, Moscou apportant une importante contribution à la création d’une base industrielle nationale et garantissant la formation professionnelle des nouveaux cadres algériens, une composante fondamentale de la coopération mise en place entre les deux pays. Si l’Égypte de Nasser était à cette époque le pilier de la politique soviétique au Machrek, l’Algérie était le partenaire le plus important au Maghreb, et la relation privilégiée entre Alger et Moscou a marqué toute la présidence de Boumediene (1965-1978), celui-ci ayant d’ailleurs vécu ses derniers jours à Moscou où, souffrant d’un cancer, il y recevait des soins médicaux.

La disparition de l’URSS d’une part et le conflit entre l’État algérien et les islamistes de l’autre, ont dès le début des années 1990, éloigné les deux pays, chacun préoccupé par des priorités intérieures qui ont, pendant un moment, relégué au second plan leurs relations avec l’extérieur. La renaissance de leurs relations fut entreprise en 2001 avec la visite officielle de Bouteflika en Russie (3-6 avril 2001), qui a donné une nouvelle impulsion aux relations bilatérales, avec notamment la signature de la Déclaration de partenariat stratégique, le premier accord de la sorte signé par la Russie avec un pays arabe ou africain. La visite officielle entreprise par Vladimir Poutine en Algérie le 3 mars 2006 a été marquée par l’annulation de la dette militaire algérienne estimée à 4,7 milliards de dollars et suivie par la signature de nombreux accords de coopération économique.

Les retrouvailles avec l’Algérie ont permis à la Russie, en pleine redéfinition de ses rapports avec le monde arabo-musulman, d’opérer un retour au Maghreb, qui demeure une zone stratégique de la plus haute importance à un moment où Moscou est engagée dans son retour en Méditerranée, et s’inquiète fortement de l’expansion des extrémismes et du terrorisme dans les pays du Sahel. Par ailleurs, la relation avec Alger est confortée par le fait que les deux pays font la même lecture du Printemps arabe, de la Libye à la Syrie, et que Moscou reconnaît le rôle de puissance régionale de son allié algérien, rôle que Moscou contribue à renforcer avec l’étendue de la coopération militaire qui lie les deux pays. En effet, la Russie est le principal fournisseur d’armes de l’Algérie, 91 % des importations d’armes de l’Algérie étant originaires de Russie. En acquérant 11% des armes que la Russie vend à l’étranger, l’Algérie en est son troisième client après l’Inde et la Chine, une place qui fait de l’Algérie un partenaire de choix depuis la réactivation de l’axe politique Moscou-Alger. Outre la coopération militaire, les deux États gaziers ont mis en place une coopération hautement stratégique dans le domaine énergétique – rappelons que Gazprom (125 milliards de mètres cubes) et Sonatrach (61 milliards de mètres cubes) représentent à eux deux 36 % de l’approvisionnement en gaz de l’Union européenne – un autre volet des relations russo-algériennes, et non des moindres.

Ainsi, s’agissant de la politique intérieure, le bilan de Bouteflika s’avère très mitigé et peut légitimement être discuté, mais son bilan en termes de politique étrangère ne fait l’objet d’aucun débat tant tout le monde s’accorde à reconnaître que, sortie de la guerre civile, l’Algérie a retrouvé sa place dans la communauté internationale, s’est engagée dans une diversification de ses partenaires tout à fait rentable et prometteuse, a imposé dans toute la région la Russie comme contrepoids fondamental à l’influence que les puissances occidentales continuent d’exercer dans la région et, portée par la puissance de son armée, s’est imposée elle-même comme la puissance régionale indispensable.

Le 17 avril 2014