Russia’s grave mistake of getting bogged down in sectarian mess

Russia’s foreign policy in the Middle East in recent decades was based on a harmonious approach that helped maintain good ties with all the players in the region without getting involved in political and sectarian wrangles.Russia’s involvement in Syria made this balance very difficult to maintain, since the Syrian conflict showed the sectarian and geopolitical fault lines of the regional powers.A main reason for the skewed balance now is Iran’s interference in Iraq and its multidimensional support for the Damascus regime, also given through groupings such as Hezbollah or other Shiite militias originating from Afghanistan and Pakistan.

Russia’s foreign policy in the Middle East in recent decades was based on a harmonious approach that helped maintain good ties with all the players in the region without getting involved in political and sectarian wrangles.Russia’s involvement in Syria made this balance very difficult to maintain, since the Syrian conflict showed the sectarian and geopolitical fault lines of the regional powers.A main reason for the skewed balance now is Iran’s interference in Iraq and its multidimensional support for the Damascus regime, also given through groupings such as Hezbollah or other Shiite militias originating from Afghanistan and Pakistan.

The Iranian involvement becomes more alarming as the conflict progresses. Tehran’s involvement in Syria and Iraq is clearly not limited to the “noble” causes of fighting terrorists, helping Syrian minorities or supporting and defending the “democratically elected president” against “terrorists.”Iran has always had far-reaching plans, primarily to counter major Sunni countries in the Gulf, chiefly Saudi Arabia, and change the regional balance of power.Iran is also pursuing its goal of exporting the revolution, which means, according to Hamid Reza Moghaddam Far, Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) deputy commander of cultural affairs, “not sending advocates and preachers to other countries, but rather exporting the ideology.”This dubious export will go well beyond the Mediterranean.This ideology is brought in Iraq and Syria by gangs like Afghan Fatemiyoun Division, a Shiite militia fighting in Syria on the side of Assad regime.According to Tasnim News Agency, this division will stay involved in Syria for as long as Islam, read, in this case, Iran’s geopolitical ambitions, does not know borders; it “will always stand by Khomeini’s divine goals.”Iran is using Shiite Muslims as an instrument in its dirty game of expanding its influence and destabilizing Sunni neighbors.Saudi Arabia and its regional allies do not have any illusions about the troubles the Iranian expansion will bring them.Thus, by tragic coincidence, Syria has become a battlefield of rising sectarian regional tensions.The attempts to ease this sectarian conflict and careful messages of peace and detente coming from the western side of the Gulf are unheard, muffled by a roar of accusations coming from the Gulf’s eastern side.

It is not that Russia cannot cope with having Iran as a rival, particularly taking into account the latter’s difficulties on the global stage. By aligning with Tehran, Moscow seems to be on the wrong side of history.

Maria Dubovikova

Despite declarations of a balanced policy that keeps it friendly with everyone and does not allow it to build alliances, Russia is actually failing to maintain this policy in Syria, even despite its will, because it is being squeezed between the players there. The success of the Astana talks and the relative success of the new Geneva round only strengthened the Iranian position, especially after Iran was recently recognized as a guarantor of the cease-fire in Syria, leaving out GCC countries. True, the GCC countries were invited to take part in talks, but Saudi Arabia cannot accept the role of spectator and the other GCC countries will not get involved without this key Gulf power. UN Syria envoy Staffan de Mistura has been urging all foreign players in Syria to not turn the Syrian sides into pawns of their own game. Deputy Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s visit to Washington signals the re-emergence of Saudi-US partnership. Moreover, it seems that in Syria, the two major players will try to overplay the until now successful trio. But is this a reasonable step? Due to certain circumstances, Russia appears to be on the same side with Iran in the Syrian game, even though it tries to stay relatively “impartial.” There is significant cooperation between Russia and Iran in many areas, boosted after Russia’s spat with Europe. Then, after all, Iran is a neighbor. It is also a dangerous rival and an absolutely unreliable friend. And between the two, Russia is choosing “an unreliable friend.” Yet it is not that Russia could not cope with having Iran as a rival, particularly taking into account the latter’s difficulties on the global stage.

Russia seems to be on the wrong side of history in this case, but it has few choices under the current shaky circumstances. The success of Astana and Geneva talks is greatly dependent on the relative friendship between Moscow and Tehran. And for Russia, it is a matter of honor to have the Syrian conflict solved through a political process. What should be clearly understood about the Russia-Iran cooperation is that there is no illusions about Iran in Moscow. Iran wishes to cooperate with the West more than with anybody else. Cooperation with Russia is not based on common values and long-term interests. There is a full pack of difficult to resolve issues between them. Iran poses an imminent threat to Russia’s interests. In Iran, there is a high level of discontent with Russia, especially its policy in Syria (that seems insufficient in Tehran’s eyes) and in all its policy toward Iran (which seems to Tehran not friendly enough: The nuclear plant is not build as fast as it was promised, the delivery of the notorious S-300s had been postponed for a long time, etc.) Currently, Russia’s answer to the question asked by Saudi Arabia — “Are you with us or with Iran?” — seems to be “with Iran.”

And expecting such an answer, the GCC is reinforcing the US presence and alliance in the region to counter Iran’s and its allies’ imminent threat. For Russia, as always, cooperation with Iran does not exclude an in-depth partnership with GCC, but Russia is interested in cooperating with the Gulf. With some GCC countries, like Qatar and Bahrain, relations are progressing well, while with other, they seem stuck or hostile, adding to the climate of mistrust. Russia is clearly making a grave mistake by getting bogged down deep in the sectarian mess and losing its impartial status, but it can hardly avoid it. But certain countries are making an even bigger mistake by expecting to overplay the existing trio, as deepening the geopolitical misunderstanding over Syria will plunge the region in an endless mess that costs dearly the civil population and the global stability. A great role Saudi Arabia could play, as a leading and powerful GCC state, would be to not urge the US to oppose the Russia-Turkey tandem, with an adjunct Iran, but to make Russia, Turkey and the US work together on resolving serious issues in Syria and Iraq, as well as to fight terrorism and minimize Iranian influence and role by actively taking part in all activities itself. That would be a worthy gambit, hardly expected, but benefiting the whole world.

Syria: An immeasurable, multidimensional tragedy

Syria’s humanitarian catastrophe is worsening daily despite the cease-fire and somewhat successful direct negotiations in Astana and Geneva. There is still fighting in some areas, making it difficult for humanitarian organizations such as the Red Cross and Red Crescent to reach civilians in those areas.

Syria’s humanitarian catastrophe is worsening daily despite the cease-fire and somewhat successful direct negotiations in Astana and Geneva. There is still fighting in some areas, making it difficult for humanitarian organizations such as the Red Cross and Red Crescent to reach civilians in those areas.

The government in most cases is unable to restore normality in “liberated” areas, or provide people there with basic needs such as electricity and water. Syrian officials are even unhappy at the burden of those areas now being completely their responsibility, with no one else to blame. Damascus’ resources are dwindling, its allies’ help is insufficient, and humanitarian aid provided by NGOs is limited compared to the scale of the tragedy.

Humanitarian organizations have limited access to areas controlled by radicals and extremist groups, not least because of the high security risks. NGOs have no access to areas controlled by Daesh, in which about 1.5 million Syrians are concentrated. The humanitarian catastrophe in Syria will deteriorate further following the operation to liberate Raqqa, as such operations have always resulted in extremely high civilian fatalities, injuries and displacement.

The humanitarian disaster is not limited to physical suffering, famine, illness or malnutrition. It has an enormous psychological impact that is practically impossible to evaluate. December saw the evacuation of east Aleppo, which lay in ruins, its people emaciated. What shocked Red Cross representatives taking part in the evacuation was that no children were crying — a sign of their internal pain at the hope, loved ones, life, home and country they have lost.

Even if the ground war ends today and true peace prevails, the war will remain in hearts and memories. Most Syrians returning home will have to restart their lives from scratch.

Maria Dubovikova

Psychological trauma is not as striking at first glance as physical wounds, but they become striking with time. Their consequences can be severe and disastrous for the whole country in the long run. Experts say rebuilding Syria will cost some $100 billion. But the human cost is immeasurable. Material things are more easily repaired than a social fabric.

Even if the ground war ends today and true peace prevails, the war will remain in hearts and memories. It will remain in its physiological consequences. Most Syrians returning home will have to restart their lives from scratch.

Many Syrians have lost contact with their relatives and have no knowledge of the whereabouts of their loved ones. People are detained by the government without prosecution, but the rebels are no saints either. People are disappearing, perishing in mass executions by Daesh, and dying in shelling and airstrikes. Many are yet to perish. These millions of personal tragedies are forming a national and global catastrophe.

There is also the near-complete destruction of infrastructure, including hospitals and schools, depriving people of basic social needs. Education may not seem so important at first glance, but the future of Syria lies in the hands of youths who are critically damaged by the conflict, and hence easily manipulated by extremist recruiters. With NGOs’ focus understandably on helping people survive, this issue is not being addressed.

Ignoring the psychological and social aspects of the humanitarian catastrophe could cost Syrian society and the whole world dearly. But there is hope because of the inherent traits of the Syrian people: Kindness, open-heartedness, generosity and hospitality. Despite their suffering and losses, they are demonstrating unprecedented resilience and love.

They help each other regardless of their political views, and are ready to share with their neighbors their last piece of bread, an example of generosity and unity amid this devastating war. Thus there is no civil war between civilians.

It is a fight for power, to realize the geopolitical ambitions of certain forces and people on both sides of the frontline, as well as their sponsors. Hopefully, Syrians’ natural warmth will be the key binding element of reconciliation and civil society, overcoming the politics that have brought nothing but war and hatred.

Initially published by Arab News: http://www.arabnews.com/node/1070051

Stop war. You are all Syrians. (by Maria Dubovikova)

Stop war. You are all Syrians. (by Maria Dubovikova)

Building a better tomorrow for the Middle East

Prominent experts and high-level officials from Russia and all around the world have been trying to find the answer to the question: “The Middle East: When will tomorrow come?”

Prominent experts and high-level officials from Russia and all around the world have been trying to find the answer to the question: “The Middle East: When will tomorrow come?”

Russia’s annual Valdai Discussion Club — a prominent, marathon-like two-day dialogue on the Middle East — has just finished. The meeting, held in Moscow, united top officials and experts from Russia and all over the world, with vivid discussions on the burning issues involving the Middle East.

The Valdai format has once again proved to be an open platform for the free sharing of ideas, views and concerns. And what is more important is that it has proved that Iranians and Saudis, Palestinians and Israelis, and Turks and Kurds can be present in one hall, despite different religious beliefs, political views and affiliations. It shows they are able to talk, listen to each other, speak, peacefully argue, find common ground — and even joke and laugh.

The key topics on the table were Syria and Iraq, Yemen and Libya, the Arab-Israeli conflict, Iran and its place in regional affairs, and separately the issue of the Saudi-Iranian confrontation. They are the key issues that are forming the general regional environment and which have a serious impact on the global agenda and stability.

All these topics were approached from both regional and global perspectives, thus involving global players from the US, Russia, EU and even India and China.

The dialogue revealed several major characteristics of the current historical momentum.

First of all, we are living in a critical moment in history, with the emergence of a new world, the true nature of which is still not clear. Russia’s role in regional affairs is evolving, and is being re-evaluated with more constructive analysis, understanding and sane criticism, instead of a reaction of panic and fear.

Raghida Dergham — the founder and executive chairman of the Beirut Institute, columnist and New York bureau chief at Al-Hayat, and whose columns appear in Arab News — talked about the importance of Russia-US cooperation for the region. She also raised Iran’s role and ambitions in the region, notably in Syria.

Under the pressure of severe challenges the region is facing, there are signs of an attempt to put aside existing differences and make steps toward cooperation, facing up to the threats, and building the future the region hopes for.

At least that is what was clearly heard in the speeches of Amr Moussa, former secretary-general of the Arab League, Nabil Fahmy, former Egyptian foreign minister, and Ebtesam Al-Ketbi, founder and president of the Emirates Policy Center.

Fahmy has assumed that the majority of the regional challenges cannot be faced without the participation of the global players. But he cautioned that this participation and assistance should be constructive, not deepening the schisms with geopolitical games.

A reconciliation in a region facing major threats could be led by Egypt, traditionally taking the cornerstone role of stabilizing player, despite the severe internal crisis it is still going though following the shock of two revolutions in three years.

This call for regional reconciliation and cooperation is coming primarily from societies that are tired of confrontation and conflict.

Even the guests from Iran pointed out that there is a strong growing middle class in Iran, which is looking forward to modernization and a reconsideration of the policies toward the region and global players. Thus Iranian speakers gave hope for a change of Iranian policies in the foreseeable future. People are looking for peace, not for confrontation.

The last panel in the conference was entitled “The Future of the Middle East: In search of a common dream.” Politically the dreams of the governments are dividing, not uniting the sides. And from this perspective future prospects are quite gloomy, as long as the aspiration for dominance and power that prevails in politics continues, leading to more wars and confrontation. The dream of one government often eliminates the dream of another.

John Bell, director of the Middle East and Mediterranean Program at the Toledo International Center for Peace in Madrid, said we appear to be in a situation where there are a lot of dreams, but an absence of positive reality; some governments are manipulating Middle Eastern societies. But these same societies, political manipulation aside, are united by the same dreams of peace and prosperity.

This brings a crucial need for the emergence of civil societies that are able to form and determine the policies of governments. And the key to this lies in education, including training to resist propaganda and manipulation and teach critical thinking.

Thus, it is only through the perspective of such societies that the Middle East has a chance to pursue the common dream of peace. Governments stay and governments go. It is time to build bridges between the people.

Article published in Arab News

http://www.arabnews.com/node/1061826

Geneva IV: Paving the path to peace

There is no longer unhealthy interest and agitation around the Geneva talks. Speculation and media manipulation have significantly decreased, enabling negotiators to concentrate more on negotiations than on popping cameras. No one expects a breakthrough from Geneva IV, but then it depends what is considered a breakthrough.

There is no longer unhealthy interest and agitation around the Geneva talks. Speculation and media manipulation have significantly decreased, enabling negotiators to concentrate more on negotiations than on popping cameras. No one expects a breakthrough from Geneva IV, but then it depends what is considered a breakthrough.

It is significant that for the first time in almost six years of bloody and devastating war, the government and inclusive opposition are ready for direct talks. Even though UN envoy Staffan de Mistura says he sees little common ground between the sides, the fact that they have matured to the point of overcoming mutual hatred and talking directly is promising.

Another positive sign is that thanks to the efforts of many players — including Russia, Turkey and Saudi Arabia — the opposition has reached the fourth round of talks more united than ever, and able to articulate its positions and demands without stalling each time due to internecine debates and disputes. Despite having little common ground, the sides seem keener on ending the war, concentrating on a political transition and fighting extremists.

Even Turkey, which had staunchly supported the opposition forces from the start of the conflict, has softened its position on the Syrian regime, admitting it is no longer realistic to insist on a solution that excludes President Bashar Assad. The fact that tough preconditions from the opposition side have disappeared from their political statements is also an important and promising sign. Removing a military solution to the conflict is a true breakthrough.

Much was done to make these achievements possible by Turkey and Russia after their own reconciliation. The Astana format, which served to back up the Geneva process, harmonized negotiations and enabled the possibility of direct talks.

The main problem is the ground forces that are not interested in a settlement of the conflict. These radicals and extremists are profiting from it. Jabhat Fateh Al-Sham, formerly Al-Nusra Front, is a major headache. Its infiltration of opposition ranks hampered Russia-US talks on the separation of radical groups and moderate opposition in east Aleppo. This paralysis led to rebel defeat in east Aleppo, which was a game changer in the conflict, at a high cost in human lives that could have been avoided.

Peace in Syria is not in the interests of extremist groups. For Daesh and other terrorists, the longer the conflict, the easier it is to radicalize and recruit. These groups could not survive in peacetime.

At the Munich Security Conference, De Mistura outlined the challenges the political process is facing, and provocations from parties that are playing spoiler. Players such as Russia and Turkey, which stand out as guarantors of the peace process, are working to elaborate mechanisms to minimize the impact of provocations and maintain the cease-fire, which is indispensable for any political process.

It is high time for Syrians to come up with a political settlement to end the violence, chemical attacks, atrocities and suffering. It is high time for the international community to join forces to help them do so.

Geneva IV will not result in breakthroughs that will immediately lead to a political process, but it could pave the way for such agreements. The political maturity of both sides gives hope for further involvement of civil society in negotiations, which will facilitate talks and an indispensable political transition.

International players should stop playing geopolitical games on the bones of innocent Syrians. The longer a political settlement is questioned by negotiating sides, and the longer the Assad regime listens more to Tehran than to Moscow, the stronger terrorist cells will become, and the harder it will be for the international community to fight them. The future of Syria and the world is at stake.

However, the start of a political process is no guarantee of peace. The devil is in the details, and disputes over many issues can lead to the continuation of the conflict in different forms. But no matter the risks and challenges, it is time for all Syrians to work together and remember that they are one nation, and that the key to peace lies only in their hands.

Article published in Arab News:

http://www.arabnews.com/node/1059851

Мир своими силами: как страны Ближнего Востока учатся вести переговоры

Женевские переговоры о судьбе Сирии начинаются в условиях, когда ближневосточная политика, возможно впервые за целый век, становится собственно ближневосточной, определяемой прежде всего региональными государствами

Женевские переговоры о судьбе Сирии начинаются в условиях, когда ближневосточная политика, возможно впервые за целый век, становится собственно ближневосточной, определяемой прежде всего региональными государствами

В конце 2016 года многие прогнозировали замедление политических процессов на Ближнем Востоке из-за смены администрации США. Предполагалось, что все игроки будут находиться в ожидании новых назначений в Вашингтоне и выработки Белым домом новых подходов к ключевым конфликтам в регионе, прежде всего к сирийскому. Прогнозы не оправдались: 2017 год на Ближнем Востоке начался довольно интенсивно.

Переговоры в Астане

Москва в период временного американского отстранения активизировала свои действия в регионе: Владимир Путин инициировал переговоры в Астане. Итоги переговоров вызывают разные оценки. Пессимисты считают их провальными, потому что по итогам первого раунда оппозиция отказалась подписывать итоговое коммюнике, а проект новой Конституции Сирийской Республики, предложенный Россией, вернее сам факт его предложения, вызвал серьезную критику со всех сторон. Оптимисты полагают, что успехом можно считать то, что новый формат переговоров состоялся, а проект Конституции, предложенный Россией, был предназначен вовсе не для того, чтобы навязывать сирийцам представления о государственном устройстве их страны, а чтобы стимулировать политический диалог.

После второго раунда переговоров в Астане, несмотря на всю скромность его результатов, можно утверждать, что точка зрения пессимистов скорее ошибочная. В нынешних условиях апробация новых форматов важна сама по себе, но более существенно то, что ключевыми игроками ближневосточного политического процесса все чаще становятся региональные акторы. Это не только Турция и Иран, но и Саудовская Аравия, которая, хотя и не участвует в переговорах в Астане, ведет диалог по другим трекам.

Акторы и медиаторы

Растущую роль региональных игроков мы можем наблюдать и на других направлениях, прежде всего на ливийском. В середине февраля была предпринята попытка провести переговоры в Каире между главой ливийского правительства национального единства Файезом ас-Сараджем и командующим ливийской национальной армией Халифой Хафтаром. Попытка закончилась провалом, но характерно, что инициативу по ливийскому урегулированию все больше проявляют именно региональные игроки — прежде всего Египет, но также Алжир и Тунис.

Мы видим очень интересный процесс: изначально возросшая де-факто, сегодня роль региональных игроков институциализируется через разнообразные дипломатические инициативы. Случилось так, что временное снижение активности США позитивно сказалось на увеличении свободы действия региональных акторов.

Любопытно, что Россия в этих условиях также демонстрирует новые подходы к ближневосточным политическим процессам. Они основаны на той идее, что глобальные игроки, такие как Россия и США, должны прежде всего играть роль медиаторов региональных политических процессов. В этом контексте показательна межпалестинская встреча, прошедшая в Москве в январе. Россия не принимала участия в этом диалоге, лишь предоставила площадку, а научный руководитель Института востоковедения РАН Виталий Наумкин выступил модератором переговоров. Итогом встречи стало коммюнике, которое подписали десяток палестинских политических партий и организаций.

Подобные мероприятия говорят о постепенном изменении характера ближневосточной политики, которая, возможно, впервые за сто лет становится собственно ближневосточной, минимально определяемой позициями внерегиональных игроков.

Линии недоверия

Основные региональные акторы, среди которых Турция, Иран, Саудовская Аравия, Израиль и Египет, зачастую не нуждаются во внешней поддержке: они ведут диалог друг с другом во множестве разных форматов и на разных уровнях. Однако общему разговору часто мешает колоссальное недоверие, царящее в регионе, подпитывающее три ключевых раскола: ирано-саудовский (иногда трактуемый как суннито-шиитский), ирано-израильский (также арабо-израильский, но он играет меньшую роль) и турецко-египетский (основанный на разных отношениях элит к политическому исламу, в частности к организации «Братья-мусульмане»).

Эти линии раскола сказываются и на сирийском конфликте, в котором на локальное противостояние налагается региональное, прежде всего между Саудовской Аравией и Ираном, и в котором каждая из сторон поддерживает определенных сирийских игроков. На это противостояние в качестве третьего уровня налагается глобальное противостояние между Россией и Западом, особенно заметное на последнем этапе деятельности администрации Барака Обамы. Линии взаимного недоверия проходят при этом как горизонтально, так и вертикально, скажем между Саудовской Аравией и сирийской оппозицией, Саудовской Аравией и США и так далее. Ситуация усложняется тем, что локальные игроки, понимая мотивацию и логику действий глобальных игроков, пытаются манипулировать своими патронами. Это делает ограниченной возможность урегулирования конфликта.

Чего ждать от Женевы

Тем не менее новые тенденции — растущая роль региональных держав и принятие внешними игроками роли медиаторов вселяют надежду. Появились данные, что к процессу в Астане хотят присоединиться новые, ранее не задействованные сирийские группировки, что сделает диалог более инклюзивным и создает больше возможностей для поддержания режима прекращения огня. Если такой режим будет поддерживаться и если турецко-ирано-российский мониторинг этого режима покажет свою эффективность, то он может лечь в основу политического процесса, который будет запущен в Женеве 23 февраля.

Этот процесс предполагает обсуждение трех основных вещей — проблемы управления Сирией, подготовки новой Конституции и проведения выборов. Прежде всего в Женеве станут ясны основные сложности конституционного проекта, который должен быть разработан и принят участниками переговоров с учетом сложностей, связанных с характером государственности и административно-территориальным устройством Сирии. Больших прорывов от женевских переговоров ожидать нельзя, но сами по себе они указывают на тенденцию к преодолению недоверия и налаживанию политического диалога.

Опубликовано изначально на РБК:

http://www.rbc.ru/opinions/politics/22/02/2017/58ad6fa89a79474ad0bc4070

Why Moscow now sees value in Syrian local councils

The major political slogan of the Bolshevik Party leading up to the 1917 Great October Socialist Revolution and the uprising itself, “All Power to the Soviets!” is now relevant to Syria.

The major political slogan of the Bolshevik Party leading up to the 1917 Great October Socialist Revolution and the uprising itself, “All Power to the Soviets!” is now relevant to Syria.

Russia has come to realize that some opponents of the Syrian regime are actually moderates rather than terrorists and that a move to empower local governments could help resolve the conflict.

The long-lasting civil war in Syria killed centralized government stone dead and caused a de facto territorial fragmentation. Although international players are currently voicing “commitment to Syria’s sovereignty, unity and territorial integrity,” it also is a fact that alternative forms of civic self-government, namely local councils, have held sway in rebel-controlled districts for some time now.

According to Al-Monitor’s sources close to the National Coalition for Syrian Revolution and Opposition Forces, the country’s local councils numbered 404 after the fall of eastern Aleppo to the forces of President Bashar al-Assad. Self-government is in the offing in Turkey’s buffer zone in northern Aleppo. Thus, one can argue that the self-organizing revolutionary movement suggested by Syrian activist Omar Aziz at the onset of the uprising in 2011 has materialized.

Until recently, the Kremlin refused to acknowledge the civil war in Syria, portraying the conflict only as Damascus’ fight against “terrorists.” Such a policy prevented Russian officials from objectively assessing local councils’ performance. Moreover, the issue is a real blind spot among many Russian politicians and pundits.

Indeed, on Nov. 8, Russian Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Maria Zakharova labeled councils in eastern Aleppo “self-proclaimed authorities” doing “what their external sponsors or backers told them” and playing into the hands of “the most radical illegal armed groups.” Russian Defense Ministry spokesman Maj. Gen. Igor Konashenkov said Dec. 13 that what eastern Aleppo had experienced was “indiscriminate terror,” rather than an opposition movement and local councils. Though Russia described self-government in formerly rebel-held areas of eastern Aleppo with broad strokes, one should note that despite “random terror,” Russia’s Defense Ministry was able to evacuate virtually all besieged fighters and their families to Idlib. At the same time, it is clear that notorious jihadists should have been detained and vetted.

However, the recapture of eastern Aleppo and the Defense Ministry's subsequent recognition of Syria’s moderate opposition appear to have reset Moscow’s attitude toward both rebels and “local power brokers.” In the end, Article 15 regarding the separation of power between local councils and central government was incorporated into Syria’s much-talked-about draft constitution produced by Russian experts and presented to the armed opposition at negotiations last month in Astana, Kazakhstan.

On one hand, such a step signals Moscow’s willingness to make concessions and to consent to Syria’s division into zones of influence within its existing boundaries. On the other hand, the move once again signifies the Kremlin’s inconsistency — characterized by the pretense of stability, the absence of a long-term Syria strategy and the influence of domestic policies on foreign ones.

Moscow’s analysts are united in stating that the draft constitution, including such controversial points as Kurdish autonomy and a seven-year presidential term, is merely an attempt to promote dialogue between all the parties concerned. Yet it is evident that a focus on “legalization” of local councils and their integration into the political conflict settlement represents an appropriate way to do that.

“Wholesale reforms” require much time and effort. The time vacuum and lack of visible achievements play into the hands of hard-line and terrorist groups. In this respect, supporting local government is the most effective and pragmatic way to restore peace for the locals, to address social needs and to create jobs after a lasting truce.

However, problems also arise. On one hand, the councils are trying to distance themselves from any armed groups. On the other hand, they need the assistance of outer forces. Ma'arrat al-Numan, a city in Idlib province, illustrates successful coordination between the local council, local coordination committees and the Free Syrian Army's Division 13, which is closely affiliated with the local administration. They jointly managed to force Jabhat Fatah al-Sham (formerly Jabhat al-Nusra) to withdraw from the region. Commanders of the armed groups and activists of local councils are quite close and the distinction between them is somewhat symbolic, even though the latter is charged with addressing pressing social issues rather than sustaining control over the areas.

Given this, an important question logically arises: How will Damascus take Moscow’s suggestion to decentralize power? As of now, the reaction is still unclear, as no one has publicly commented on the situation on the ground. However, the pro-government Syrian media tend to be quite skeptical about the performance of local councils. They stress that the councils fail to meet even the basic needs of the population, despite the assistance of nongovernmental organizations and funding provided by the West and the Persian Gulf states.

Meanwhile, the regime has long been playing its own game with local councils. Damascus maintains leverage in opposition-held areas, first and foremost, by demonstrating its sustained, indispensable role in providing essential public services — paying wages to teachers and money to pensioners who have not been reported as involved in opposition. At the same time, the regime has openly opposed any challenge to its monopolized areas such as providing public services and an alternative educational and health care system. Damascus launched deliberate airstrikes in the cities where local councils had been most successful and thereby had posed a substantial challenge to the regime. That was the case, for example, in Ma'arrat al-Numan, Douma and Darayya. However, in some areas, the administration has sought reconciliation with local councils for its own benefit — as it did, for instance, in Quneitra and Daraa provinces.

At the same time, since the emergence of the first local councils five years ago, the opposition has failed to agree on a model of local administration and self-government, or to vest them with political functions. As a result, with the rare exceptions of the Kabbun and Ma'arrat al-Numan assemblies, councils provide only some public services, and they do not have any administrative duties or executive or administrative powers. The idea of holding elections to provincial councils that represent various administrative layers, interact with the United Nations and other bodies and can directly conduct political reform in the long run has not been fully implemented. As of now, only eight councils of the kind have been formed in Syria.

Local councils can possibly initiate cooperation with the regime and with the Russian officers at the Center for National Reconciliation, based at the Khmeimim military base. Some sources on the ground told Al-Monitor that there are Christians in the groups who cooperate directly with the councils and among activists. After some “indoctrination,” it may prove valuable to have local councils recognized by the regime as civil structures.

Remarkably, Syrian Kurdistan’s positive experience with local councils may well be studied and used across Syria. The Kurdish Democratic Society Movement headed by the nationalist Democratic Union Party is of particular interest to those who want to establish fully autonomous, civil-military self-government structures; consider the Manbij Military Council, for example. To streamline the work of local councils and understand their role in the transition to peace, it is important to make good use of the experience being gained during the civil war.

Initially published by Al Monitor: http://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2017/02/russia-syria-value-local-councils-shift-damascus.html#ixzz4ZLdLvOqR

Moving towards Geneva: Giving peace a chance

Syria is moving to the fourth round of the Geneva talks. Two days of inclusive talks in Riyadh, bringing to the negotiation table the expanded Syrian opposition, including the Astana delegation and the Syrian Higher Negotiations Committee, finished yesterday.

Syria is moving to the fourth round of the Geneva talks. Two days of inclusive talks in Riyadh, bringing to the negotiation table the expanded Syrian opposition, including the Astana delegation and the Syrian Higher Negotiations Committee, finished yesterday.

The opposition was harmonizing its positions on the threshold of the new Astana round, setting the priorities for Geneva Talks and discussing the outcomes of the previous Astana meeting.

The Astana meeting did not replace the format, but became a supplementary in-strument, a back-up tool for the Geneva negotiations. Astana permitted the realiza-tion of ceasefire, and the first round of talks resulted in the elaboration of trilateral monitoring mechanisms of the ceasefire regime in Syria, guaranteed by Turkey, Russia and Iran.

On February 15-16, the Kazakh Foreign Ministry will host another round of talks, welcoming delegations from the Syrian government and the rebel side, along with the UN Special envoy for Syria, Staffan de Mistoura, and the delegations of three guarantors.

Jordanian and the US delegations are also invited to take part in Astana II.

Resolving problems

The Astana format is set to solve the problems preventing the Geneva format from being a success, by instituting the communication process and resolving ground is-sues, mostly related to the military sphere, and paving the way for political resolu-tion and the long-awaited and inevitable transitional process.

The Geneva talks are set to be held on February 20. A lot has changed since the previous round. The third round practically did not leave hope for a political solu-tion. The Opposition, both moderate and otherwise, was so much fragmented, that it could not come to any agreement even within its own ranks. The International community was supporting separate opposition groups, thus somehow fragmenting them even more and politicizing the whole negotiation process, putting it in the framework of global geopolitical rivalries.

The major changes in the global sphere, the focus of the US on presidential elections first and then on the cataclysms in face of Trump’s administration, with the West watching the goings on in Washington, together with changes on the ground in Syria have significantly changed the situation and prospects of the negotiations.

The foreign states have cut their financial support to the rebel groups, and there are practically no more voices calling to topple the Syrian regime by force.

As was stated by prominent Syrian dissident Louay Hussein, “the armed conflict for the state is over”, and the majority in the opposition are going back towards a political struggle. Even though Hussein’s conclusions are premature, his words have a grain of truth.

The Syrian opposition has become more united and amenable. However, the Islamist fractions, that have formed a new alliance recently, are reportedly going to launch new attacks on the government’s positions. But most likely from the general perspective, such a decision is counterproductive primarily for themselves.

Maria Dubovikova

The Syrian opposition has become more united and amenable. However, the Islamist fractions, that have formed a new alliance recently, are reportedly going to launch new attacks on the government’s positions. But most likely from the general perspective, such a decision is counterproductive primarily for themselves. Such attempts to disrupt negotiation and political process do not correspond to the expectations of the majority of the rebels and opposition forces. They alienate themselves from the political process, lose credibility, drifting to the terrorist Islamist formations in the company of which they have all chances to end up their fight. But this will hardly inflict significant damage to the negotiation process.

Assad’s stubbornness

Russia in Syria: domestic drivers and regional implications

Over the past year, Russia has become an increasingly pivotal player in the Syrian war and, by extension, in the broader Middle East. Amidst the noise Russia’s impact in Syria has caused, the underlying drivers of its strategy – domestic, security and ideological – remain too often ignored. As a result, Russian decisions regarding Syria often seemed unpredictable and irrational to observers. However, Hanna Notte argues in her guest contribution, published by KAS and Maison du Futur, Russia’s strategy and fundamental interests in Syria have been remarkably consistent over the past six years.

Over the past year, Russia has become an increasingly pivotal player in the Syrian war and, by extension, in the broader Middle East. Amidst the noise Russia’s impact in Syria has caused, the underlying drivers of its strategy – domestic, security and ideological – remain too often ignored. As a result, Russian decisions regarding Syria often seemed unpredictable and irrational to observers. However, Hanna Notte argues in her guest contribution, published by KAS and Maison du Futur, Russia’s strategy and fundamental interests in Syria have been remarkably consistent over the past six years.

To download a paper you can clicking the cover.

Research by our member Hanna Notte was made for Konrad Adenauer Center.

Russia and the GCC within the regional power constellation after the Iran nuclear deal (Russian perspective)

Russia's relationship with the Persian Gulf and the independent Arab monarchies, which have formed in the region over the past century, is proving complex and malleable. It ebbs and flows, characterized by significant political differences, which are related to various aspects of regional and global politics and are ultimately also a function of internal political transformations, both within Russia itself and the states of the region.

Russia's relationship with the Persian Gulf and the independent Arab monarchies, which have formed in the region over the past century, is proving complex and malleable. It ebbs and flows, characterized by significant political differences, which are related to various aspects of regional and global politics and are ultimately also a function of internal political transformations, both within Russia itself and the states of the region.

However, it should be pointed out that – all disagreements and heated discussions about the Syrian crisis and the Iranian nuclear deal notwithstanding – Russia and the GCC have never been such close partners, as they are during this current complicated and painful turn in Middle Eastern history, in that they share a wide range of common interests and understand each others' concerns. There is a mutual impact between, on the one hand, prolonged regional destabilization, multiple sources and theatres of violence and the loss of governability in the region, and the internal processes within the GCC member states, on the other. The GCC, a political-military alliance with great financial and economic potential, has - in Russia's view - transformed into a real power centre, exercising leverage on the overall situation not just within the region.

Everything is relative, so the mutual appeal between Russia and the Persian Gulf is best understood in its historical context. Let us take, for instance, the longstanding relationship between Russia and Saudi Arabia, which plays a leading role in the GCC:

The Soviet Union was one of the first states to recognize, and establish diplomatic relations with, the Saudi Kingdom in 1932. The Soviets viewed the momentum towards integration on the Arabian peninsula as a progressive development, especially against the backdrop of the colonial policies of Western powers, which had competed to divide the spoils of the Arab world amongst each other. The Saudis never forgot that Moscow, in those difficult initial years of the Kingdom's development, provided Riyadh with oil products, especially gasoline. This interesting historical fact must appear amusing and paradoxical today.

Later, after the Russian Ambassador was recalled from Riyadh, bilateral relations were frozen for a protracted period. The reason was not any foreign policy disagrement, but rather the internal political repression arising within the Soviet Union, which claimed many respected diplomats as victims.

During the post-World War II period of bipolar confrontation, the Soviet leadership viewed the Gulf region as a sphere of Western preponderance. This view was reflected in Soviet ideology at the time, which divided the Arab world into states characterized by a Socialist orientation and perceived as acting compatible with Soviet foreign policy doctrine, and into the «reactionary» oil monarchies, considered US satellites. This artificial distinction was also fuelled by Nasserist Egypt, which at the time was ambitious to spread Arab nationalism across the region, especially towards the Arabian peninsula with its significant oil resources. Soviet Middle East policy was then undoubtedly driven by apprehensions about Cairo's intentions, and it was occasionally difficult to establish, who was exercising the greater influence on whom.

A reinstatement of relations between Russia and Saudi Arabia at the end of the 1970s – a period when conditions seemed ripe for reconciliation – was complicated by the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, which caused great damage to Moscow's position in the Muslim world. It was not until the 1990s that both countries established diplomatic representations in each other's capitals, though bilateral relations were overshadowed by a whole range of irritants, such as the conflict in Chechnya and events in Kosovo. While the Saudi perspective on these conflicts prioritized the need to protect the Muslim population, the Russian leadership, urging the reestablishment of constitutional legality in Chechnya and refusing to recognize Kosovar independence from Serbia, looked at the situation through the prism of international legal norms, such as the sanctity of territorial integrity and the principle of noninterference in internal affairs.

Russia's internal problems in the 1990s, causing it to reduce its political activity and economic ties in the Middle East, additionally complicated relations with Saudi Arabia, as well as the other GCC states. To many in the world, Russia appeared to have turned its back on the region. This impression was reinforced by the fact that Moscow, against the backdrop of rapidly unfolding democratic changes inside Russia, embarked on an increasingly pro-Western oriented foreign policy course. Hence, the Persian Gulf was not so much looked at from Moscow as a region that ties should be fostered with bilaterally, but its importance was rather assessed within the overall context of Russia's partnership with the US, which was to provide the framework in which to devise a reliable Middle Eastern regional security system[1].

Russia's return to the region from the early 2000s then occurred under very different circumstances. There was a change in the very paradigm of Russian-Arab relations, which became mutually beneficial and evolved in different spheres. Purely pragmatic considerations assumed priority: the support of a stable political dialogue, whatever the disagreements, the strengthening of economic ties, as well as regional security. On this basis, Russia started building relations – rather successfully – not just with traditional partners, but with all Arab Gulf states, which were gaining in political and economic weight at the time.

During the same period, the GCC underwent a process of increasing institutionalisation internally, for instance in the spheres of common defense, coordination of actions on the international stage, coordination of oil policies, as well as economic integration. Given the emergence of this new, more integrated center of power in the Gulf, relations with Russia acquired an additional dimension.

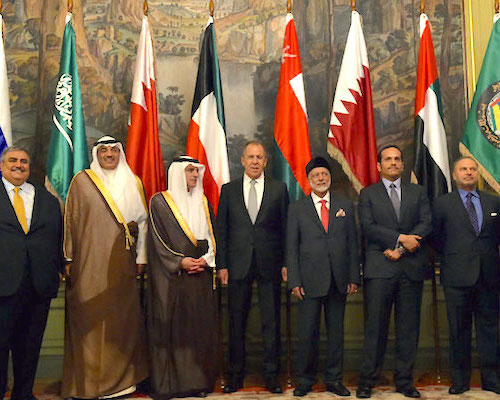

From 2011, a Russian-GCC dialogue started to develop in parallel to the nurturing of bilateral relations; the former was aimed at the convergence and coordination of the participants' positions on regional and global problems of common interest, as well as the development of trade and economic relations. Five rounds of talks between all foreign ministers were held in Abu Dhabi, Riyadh, Kuwait, Moscow, as well as New York on the sidelines of the UN General Assembly. Regional security, especially the fight against international terrorism and a political solution for the conflicts in Syria, Iraq, Libya and Yemen – both intended to stabilize the Middle Eastern situation more broadly – became the central item on the Russia-GCC agenda. In this context, the Gulf participants emphasized, in particular, Iran's regional role and its relations with Russia, since they viewed Tehran as the main threat in the region.

The extent to which questions related to Gulf security are of utmost priority to the Arab states of the region is well understood in Russia. These questions already acquired heightened significance in 1990 during the First Gulf War. At that time, the priority for both the GCC and, by the way, Russia was to neutralize the threat emanating from Iraq. Following the overthrow of Saddam Hussein in 2003, the GCC started to view Iran – a state with substantial military might and wide-ranging possibilties to influence the Gulf states through its support for their Shiite communities – as their main enemy.

As a result of this development, the challenges of Gulf regional security acquired a new, more complex character, especially considering the heavy legacy of relations between these two centers of power in the region, a legacy that has its roots in the emergence and spread of Islam as a world religion.

The destruction of the old state foundations and the social and political upheavals, which afflicted the entire MENA region with the beginning of the «Arab Spring», forced the GCC to adapt to changing circumstances and to seek additional resources, in order to forestall the spillover of destabilization into the Persian Gulf at a time when power relations between major regional players were in flux. Egypt, living through two revolutions and suffering from their disruptive consequences, was temporarily weakened. Syria and Iraq have been torn by internal strife between groups close to either Saudi Arabia or Iran. And Turkey, which claimed the universality of its model of «Islamic democracy», has ceased to be regarded in the Arab world as a role model, given its growing domestic and external problems.

Unlike Jordan and Morocco, which swiftly embarked on a path of political modernization, the Saudi kingdom decided for more gradual development, starting by introducing economic reforms. And this is understandable: Saudi Arabia, as the guardian of the holy sites of Islam, carries a particular responsibility for the maintenance of stability, especially at a time when it found itself, as officials in Riyadh argued, caught between two perils: that of revolution and acts of terrorism, on the one hand, and that of surging Iranian regional ambitions, on the other. It should be noted that, while these worries shared by Saudi Arabia and its Gulf allies were not entirely unfounded, they were in some instances overexaggerated, according to most Western and Russian experts.

It is certainly true that Shiite Iran has enhanced its position in Iraq over recent years, paradoxically enabled by the 2003 American invasion of Iraq, which changed the sectarian balance in positions of power in favour of the Shia, a fact that Iran has used in its favour. Saudi hopes that the Assad regime, close to Iran, would be swiftly overthrown did not materialize. Iran's influence in Lebanon, exercised through the militarily well-equipped Hezbollah movement, also increased. And at the same time, the Shia opposition in Bahrain became more active, as did the Houthis in Yemen, which are considered an outright product of Iran, though this is well known to be a stretch of logic.

Developments North to the Gulf, where a Tehran-Damascus-Hezbollah axis was perceived to form, as well as South, where the Houthis overthrew a legally elected President, were seen by the Arab Gulf states as a real threat to both their security and very existence. A new strategy, comprising a whole range of political, military, financial, economic and propagandist counter-measures, had to be devised. Changes at the top echelons of power in the Saudi kingdom hastened this strategy, which was ultimately intended to contain Iran, into action.

Given these assessments of developments in the Middle East, which are prevailing among circles in the Gulf, the US' changing regional policy, especially in relation to Iran, and its possible impact on regional relations, has been of particular concern. Should recent US policy be understood as the manifestation of a new regional strategy, aimed at rapprochement with Iran and the creation of a new regional equilibrium, or rather as a tactical feat? Especially Saudi Arabia viewed the toppling of Hosni Mubarak as resulting in the loss of a trusted ally and, even worse, as evidence of the unreliability of American patronage. America's flirtation with the Muslim Brotherhood, ascending to power at the time, caused yet more suspicion, which was then further exacerbated by President Obama's decision to conclude a nuclear deal with Iran. The not unfounded Saudi allegations that the US' policy of supporting Shia authoritarian leaders in Baghdad further allowed Iran to enhance its sphere of influence in Iraq, became an additional irritant in Gulf-US relations. The two sides also differed sharply on how to deal with the conflict in Syria. US policy in Syria was regularly criticsed in the Gulf as weak and inconsistent. As a result of the above-discussed irritants, and for the first time in history, US-Saudi relations were seriously tested, a development which reached its apogee in Riyadh's renouncing of the strategic partnership and heralding a «sharp turn» in its foreign policy[2].

Worries about losing the US as the traditional security guarantor in the region also precipitated the GCC's activisation of political contacts with Russia, including at the senior level. The Saudis figured it wise to assess the extent to which Russia could play a moderating role with respect to Iran, as well as to broaden their foreign policy ties in the international arena, given the new system of flexible and self-regulating balances in the region. Russia, in turn, had already from the early 2000s adopted a balanced foreign policy course intended at the levelling of relations with states of the «Arab bloc», which it viewed as an increasingly influential player and serious partner not just in the region, but also on global political and economic issues.

The Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), signed between Iran and the «P5+1» on July 14, 2015, generated a whole range of commentary and prognoses. Two opposing camps, each assessing the deal in terms of its likely global ramifications for the nuclear non-proliferation regime, as well as its impact on Iran's regional politics, emerged.

The JCPOA's opponents in the US, like those in the region itself (including Saudi Arabia and the other GCC states) are far from convinced that the deal will lower Tehran's nuclear ambitions and moderate its regional strategy. Some even fear a regional nuclear arms race, driven by Iran's apprehensive neighbours[3]. The Gulf States do not hide the fear that the financial resources released to Iran post-sanctions relief will be used by Tehran to support the pro-Iranian forces and movements within the entire so-called «Shia crescent». The JCPOA's supporters, on the other hand, argue that the deal will not lead to a distortion of the region's military balance and that the US remains committed to its security guarantees in the Middle East. They also hold that the deal will strengthen moderate elements in the Iranian leadership, which compete with those who continue to support a harder line, especially on Syria. According to the supporters' logic, an Iran emerging from international isolation will act more responsibly, be ready for compromises, and the other Gulf states, having received guarantees that they will be protected against possible Iranian expansionism, will equally conduct a more restrained foreign policy in the region.

The agreement with Iran did not have any negative impact on Russia's relations with the Gulf countries. There is even reason to argue that – the disagreements regarding Iran and the Syrian crisis notwithstanding – meetings and conversations at the heighest political and diplomatic level became more frequent and assumed a more pragmatic outlook.

President Putin, for instance, met with King Salman in Antalya in November 2015, and with Deputy Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman Al Saud in June 2015 in St. Petersburg, as well as in October of the same year in Sochi. Of course, in view of the complexity and multifaceted nature of the situation prevailing in the region, it was difficult to expect any major breakthroughs. Nonetheless, the two sides agreed on those issues, on which they differ most acutely and agreed to continue the political dialogue and cooperation in the trade and economic sphere. A mutual understanding prevailed that differences, whatever they may be, should not become a pretense for breaking relations. Both sides were cognizant of the fact that their disagreements were outnumbered by their converging interests and approaches on a wide range of issues on the regional and international agenda, including the Middle East peace process, regional security (including in the Persian Gulf), the promotion of a dialogue among civilizations, the fight against terrorism, extremism, piracy and drug trade. Such agreements, if carried out by both sides, would in themselves be a good achievement, if compared with the ups and downs in the history of relations between the two countries.

It is possible that the change in the very style of negotiations – from emotional outbursts to candid, business-like conversations – occurred precisely because both sides recognized their own and their respective partner's important role in averting the materialization of worse-case scenarios in the region. This is especially true after Russia called for a broad antiterrorist coalition and started supporting the Syrian army decisively with airstrikes.

It is also worth pointing out a special relashionships between Russia and the Kingdom of Bahrein which are on the rise in all spheres – political, economic, banking, scientific, cultural etc. The relationships of the kind are based on close personal ties on the highest level between President Putin and His Majesty the King Hamad who had been visiting Russia four times during the last six years.

The Russian side, in the context of bilateral and multilateral (with the GCC) consultations, has been eager to convey to its Arab Gulf partners which regional and global considerations drive its policy in the Middle East. This has concerned, in particular, Moscow's relations with Tehran and its views of Iran's regional role, as well as Russia's perspective on international cooperation in the fight against ISIL and other terrorist organizations, which instrumentalize Islam to hide their political objectives.

It is critical to pause and discuss these issues, which take a central place in the Russian-Arab common agenda, in somewhat greater detail – especially given that mutual mistrust and mistaken interpretations of the respective other's intentions and motivations prevail in both the Gulf countries and Russia. From time to time, distorted ideas about Russian strategy in the region circulate in Gulf political circles.

For instance, before the Moscow meeting between the Russian and GCC foreign ministers in May 2016, the Al Hayat newspaper alleged that Iran assumes «the central place in Moscow's system of regional and international alliances», that «whoever rules Iran, be it radical or moderate mullahs, or even the Revolutionary Guards, Moscow views its bilateral ties with Tehran as of overriding concern, whether the Gulf Arabs like it or not» [4]. It is also no secret that, besides those who support building a constructive relationship with Russia, there are also those in Saudi Arabia who believe that an «either-or» choice – being with the Saudis or with Iran – will be inevitable for Russia[5].

Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov addressed these questions, which appear of particular concern to the Gulf, during yet another round of the Russian-GCC strategic dialogue in Moscow. At the joint press conference with his Saudi counterpart Adel al-Jubeir, Lavrov noted that any country has the right to develop friendly relations with its neighbours and to strive to grow its influence beyond its borders. He also emphasized that this has to be done with full respect for the principles of international law, transparently, legitimately, without pursuing any hidden agendas and without trying to interfere within the internal affairs of sovereign states. The Russian side has also always warned of the dangers associated with portraying disagreements between Iran and the GCC as reflecting a split in the Muslim world. Russia believes it is unacceptable to further provoke the situation exploiting sectarian prisms[6].

The majority of Russian experts view Iran as one of Russia's major southern neighbours, with whom mutually advantageous cooperation on a wide range of bilateral, regional and international questions – including trade, energy and (military) security – is absolutely essential. Not just the Middle East counts here, but the entire Eurasian context. Russia is interested that Iran become a member of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), a political alliance comprising non-Western states, which was founded by China and Russia.

Given these considerations, it is not realistic to confront Russia with an «either-or choice»: either Iran or the GCC. And though Russia and Iran have many common interests and their cooperation looks promising, their relationship is not without challenges. Moscow's and Tehran's foreign policy objectives coincide in some areas, but diverge in others, depending on the concrete circumstances. Russia recognizes Iran as a major player in the Middle East, yet like the Arab states does not want Tehran to acquire nuclear weapons. And the Rouhani regime understands perfectly well that Russia cannot build relations with Iran to the detriment of the GCC states' security. In Syria, Russia and Iran form a close military alliance, which however is not tantamount to a common political strategy. While both Moscow and Tehran seek to prevent the victory of Islamist extremists, their long-term goals and visions for a post-Assad Syria differ substantially. Russia is not set on retaining Assad personally, or the Alawite minority, in power, but is principally concerned with the integrity of the Syrian state, albeit a reformed one friendly to Moscow. In the security realm, Russia also closely coordinates its actions with Israel and therefore views Iran's reliance on Hezbollah suspiciously[7]. Iran's most prominent politicians are also far from contemplating the formation of an outright alliance with Russia. As Rouhani stated, «good relations with Russia do not imply Iran's agreement with any of Moscow's actions.» [8]

In general, many Russian and Western experts agree that, regarding Syria, there is Russian-Iranian agreement on the basis of a situational confluence of interests, but that one cannot speak of a full-fledged military alliance between the two powers[9]. Unlike Tehran, Moscows maintains pragmatic contacts with a wide range of political forces inside Lebanon, eager to support national consensus and to prevent a slide of the country into the abyss of violence and religious strife. And regarding Yemen, their positions equally clash. While Tehran unequivocally supports Ali Abduallah Saleh and the Houthis, Russia has adopted a more neutral position on the conflict.

Drawing conclusions, it is critical to emphasize that Moscow does not support any Iranian great power ambitions in the Persian Gulf and categorically avoids interference in the Sunni-Shiite conflict, aware that - in conditions of acute rivalry for spheres of influence in the region - Iran instrumentalizes various Shiite forces in pursuit of its narrow political interests. Relations with Saudi Arabia are without a doubt valuable in themselves for Russia. Therefore, it is important to appreciate, just how difficult a balancing act it is for Moscow to simultaneously develop what it views as an indispensible partnership with the Saudi kingdom, to strengthen friendly ties with the other Gulf monarchies and to deal successfully with its Southern neighbour Iran, with which it shares a centuries-long history. Especially at the current stage, when the regional confrontation has gone too far and, most alarmingly, has become conceived as a clash between the two religious centers of the Muslim world, the Saudi leadership has decided to contain Iran by force.

As the two opposing camps deplete their resources, and the international community feels increasingly tired and powerless to stop the vicious circle of violence, conceptualizing a new regional security order, as proposed by Russia, will become all the more urgent. The Arab states have agreed in principle to such an initiative, but are against Iranian integration into a regional security system until Tehran starts pursuing a policy of good-neighbourliness and non-interference. But without Iran, the Russian project is not viable. Therefore, Russia has signalled its readiness «to use its good relations with both the GCC and Iran, in order to help create the conditions for a concrete conversation on the normalisation of GCC-Iranian ties, which can only occur through direct dialogue.» [10]

However Russian-American relations will develop, the Gulf States need to understand that, in recent years, the balance of power in the Middle East has been changing, alliances have been forming and breaking. The level of unpredictability is growing, new risks are emerging. Today, the US' allies in the region are not necessarily Russia's enemies, in the same way that Moscow's friends are not Washington's foes. All their disagreements about Syria notwithstanding, a further escalation in the Gulf – a region of utmost importance for the world economy and global financial systems – is not in the interest of either power. In the search for what would be a historical reconciliation in the Gulf, the common terrorist threat posed by ISIL and Al Qaeda could be a critical uniting factor. The number of supporters of the «caliphate» in Saudi Arabia and in the South of the Arabian peninsula is far from insignificant. Both also have ambitious plans for economic development and are very interested in creating a favorable external environment for their aspirations.

Dr. Alexander Aksenenok, Ambassador (ret), member of Russian International Affaires Council, senior researcher, Institute for Oriental Studies, Russian Academy of Siencies.

[1] См. Свободная мысль, Россия и Саудовская Аравия: эволюция отношений, Косач Григорий, http://svom.info/entry/608-rossiya-i-saudovskaya-aravia-evoluciya-otnosheni/

[2] см. http://lenta/ru/articles/2013/10/23/unfriended/.

[3] См. РБК, Ричард Хаас, Скрытая угроза: чем опасно ядерное соглашение с Ираном, http://daily.rbc.ru/opinions/politics/16/07/2015

[4] «Москва арабам: Иран наш первый союзник», «Аль-Хаят», 19 февраля 2016 года, http://www.alh

[5] «Аль-Хаят», 26 февраля 2016 года, http://www.alhayat.com/m/opinion/14165741 ayat.com/m/opinion/14041679

[6] Выступление и ответы на вопросы СМИ министра иностранных дел России С.В.Лаврова, http://www/mid/ru/foreign_policy/news/-/asset_publisher/cKNonkJE02Bw/content/id/...

[7] Russia and Iran: Historic Mistrust and Contemporary Partnership, Dmitry Trenin, Carnegie Moscow Center, http://carnegie.ru/2016/08/18/russia-and-Iran-historic-mistrust-and-contemporary-part...

[8] См. Газета RU, 06.03.2016

[9] См. Брак по расчёту. Перспективы российско-иранского регионального сотрудничества, Николай Кожанов, Россия в глобальной политике, №3 май-июнь 2016

[10] Выступление и ответы на вопросы СМИ министра иностранных дел России С.В. Лаврова 15.09.2016, http://www.mid.ru/foreign_policy_/news/-/asset_publisher/cKNonkJE02Bw/content/id/...

سوريا: ما المعادلة بعد مؤتمر أستانة؟

IMESClub MESClub vice-president Nick Soukhov took part in the live dialogue on the France 24 Arabiya on January, 19, 2017: Syria - what the equation after the Astana?

IMESClub MESClub vice-president Nick Soukhov took part in the live dialogue on the France 24 Arabiya on January, 19, 2017: Syria - what the equation after the Astana?

مفاوضات مرتقبة في أستانة بشأن الصراع السوري مقررة يومي الاثنين والثلاثاء القادمين. جولة أخرى من المحادثات السورية السورية لكن هذه المرة كل شيئ اختلف في الميدان السوري كما على الساحة الإقليمية والدولية. مهندسو أستانة مختلفون عن مهندسي جنيف، وشاغلو مقاعد طاولة مفاوضات أستانة مختلفين عن من جلسوا إلى التفاوض في جنيف. الروسي والأتراك سيرعون المفاوضات والأمركيون مدعوون لكن لم يعرف بعد إن كانوا سيحضرون أو من سيرسلون ولا بأي نية سيشاركون. سيكون على الطاولة إيرانيون وسيغيب عنها الخليجيون. فهل سينجح مؤتمر أستانة حيث فشل آخرون ؟