Les destins professionnels des lauréats des écoles supérieures soviétiques dans les pays du Maghreb

Les destins professionnels des lauréats des écoles supérieures soviétiques

Les destins professionnels des lauréats des écoles supérieures soviétiques

dans les pays du Maghreb[i]

Nikolay Soukhov

La situation socio-politique intérieure et les incitations au départ du Maroc

Après l'accession à l'indépendance, le Maroc - comme d'autres pays africains dans les années 1950-1960 - s'est trouvé face à la tâche de devoir former des jeunes dans les secteurs les plus divers de l'économie nationale. Tâche très difficile dans un pays où il n'y avait pas d'école supérieure nationale (la première université - à Rabat - a été créée en 1957, mais n'a ouvert officiellement qu'en 1959). Parmi les principales raisons qui poussaient les jeunes marocains à partir faire leurs études supérieures en Union soviétique durant les premières années de l'indépendance, figurait l'impossibilité de le faire dans leur pays.[ii]

Pierre Vermeren, chercheur français en histoire contemporaine du Maroc, remarque que, vers le milieu des années 60, les classes moyennes urbaines s'inquiètent face à un enseignement supérieur qu’elles jugent incapable d'assurer une promotion sociale pour tous (Vermeren, 2006 : p. 48). Le Maroc compte à cette période moins d'une dizaine de milliers d'étudiants. L'Union générale des étudiants marocains (d'obédience istiqlâlienne), l'Union nationale des étudiants et le Syndicat indépendant des étudiants (proche de l'UNFP) s'associent pour manifester contre la doctrine Benhima, accusée de briser le processus d'arabisation, et aussi contre la discrimination à leur égard par rapport aux spécialistes formés en France.

Les étudiants protestent aussi contre les conditions matérielles, jugées médiocres, de leurs études. Les grèves des années 70, qui ont démarré en janvier à la faculté de médecine, ont pour mot d'ordre « l'allègement des programmes » et une « révision du système d'attribution des bourses ». Ces grèves sont de plus en plus fréquentes au sein des lycées et des universités du Maroc. Elles fédèrent autour d'elles les organisations syndicales des étudiants et des professeurs, qui se solidarisent avec les étudiants. Les autorités hésitent sur la marche à suivre ; elles démantèlent en octobre 1970 l'ENS de Rabat, haut lieu de la contestation.

Les événements de mai 1968 en France surviennent dans un contexte marocain survolté. Pour les étudiants musulmans s'ajoute la défense du mouvement national palestinien, devenue essentielle après l’humiliante défaite arabe de juin 1967. Le tiers-mondisme et l'anti-impérialisme de Boumediene en Algérie voisine renforcent cet état d’esprit.

La génération estudiantine des années 1967 à 1973 se caractérise par son opposition radicale au pouvoir. Elle se retourne d'abord contre les appareils politiques nationalistes, jugés impuissants face au pouvoir personnel du roi. Plus ouverte socialement que la génération précédente grâce à la politique scolaire mise en place après l’indépendance, cette nouvelle génération a vu émerger en son sein des éléments révolutionnaires. Des factions et différents mouvements ont été fondés ; «23 mai» et «Ilal amam» (en avant), par exemple, formaient le front des étudiants marxistes-léninistes. En 1970 est créé le Mouvement marxiste-léniniste marocain, qui représente l'avant-garde des masses populaires sur la voie de la révolution. La prise de contrôle de l'UNEM est pour eux la première étape. Mais la répression s'abat sur le mouvement étudiant dès juin 1971, provoquant son passage à la clandestinité (Vermeren, 2006 : p. 50).

La situation socio-politique décrite ci-dessus constitue la deuxième raison importante - politique - qui poussait les étudiants marocains à partir faire leurs études dans les écoles supérieures soviétiques. Ainsi la crise de l’enseignement national marocain, d'une part, et la situation politique intérieure de la fin des années 60 et 70 d'autre part, motivaient ce choix.

Pour illustrer ce postulat, il suffit de regarder la liste des organisations marocaines bénéficiaires des bourses accordées par le gouvernement soviétique :

- La Jeunesse du Parti du Progrès et du Socialisme (P.P.S.), ancien PCM

- La Jeunesse du Parti de l'Istiqlal (P.I.)

- La Jeunesse du Parti de l'Union Socialiste des Forces Populaires (U.S.F.P.)

- L'Union Marocaine du Travail (U.M.T.)

- L'Union Générale des Travailleurs Marocains (U.G.T.M.).

Lors des entretiens, les lauréats de ces générations ont reconnu qu'ils avaient des problèmes avec la police marocaine, suite à leur participation aux émeutes étudiantes. Le départ vers un pays inaccessible aux services secrets marocains (l'exemple de la disparition de l'opposant Mehdi Ben Barqa en juin 1966 à Paris était dans tous les esprits), équivalait dans certains cas, à de la survie.[iii] Les militants des groupes radicaux d'étudiants, qui réussissent à cette époque-là à partir étudier en l'URSS, s’y sont attardés, en attendant la fin de « l'époque de plomb », pour longtemps, parfois pour toute leur vie.[iv]

Puis, dans les années de relative stabilisation de la situation politique intérieure au Maroc, comme l'état de l'enseignement était resté complexe, le flux régulier d'étudiants vers l'URSS et les autres pays du bloc socialiste s’est prolongé.

Puis, dans les années de relative stabilisation de la situation politique intérieure au Maroc, comme l'état de l'enseignement était resté complexe, le flux régulier d'étudiants vers l'URSS et les autres pays du bloc socialiste s’est prolongé.

* * *

Les étudiants tunisiens partaient pour des études en URSS dans le cadre de la politique de l'État tunisien de formation des cadres nationaux. Ils étaient particulièrement motivés par le problème du développement insuffisant du système national de formation, commun aux pays en voie de développement de l'époque des « réveils de l'Afrique ».

L'absence de motivations sociales et politique - caractéristiques du Maroc - a probablement engendré un plus petit nombre de lauréats des écoles supérieures soviétiques en Tunisie.[v]

La situation était différente en Algérie, où le gouvernement algérien envoyait des étudiants en Union soviétique, en fonction des priorités de sa politique intérieure et étrangère. L'État avait besoin de médecins, d'ingénieurs et de militaires. Cette circonstance a déterminé le taux de spécialistes civils et militaires formés pour l'Algérie pendant la période soviétique : près de 4000 civils et plus que 8000 militaires.

Relations économiques et politiques entre le Maroc et l’URSS.

En même temps, l'Union soviétique était devenue de plus en plus attirante pour les Marocains. C'est au printemps 1958 qu'ont commencé les échanges commerciaux intensifs entre l'URSS et le Maroc. En échange du pétrole soviétique, d'équipement industriel et de bois, le Maroc livrait des oranges, des conserves de poisson, de la laine, de l'écorce de chêne-liège. L'établissement officiel de relations diplomatiques s'est concrétisé par l'échange d'ambassadeurs le 1er octobre 1958. Les visites du Président du Soviet Suprême de l'URSS, Léonid Brejnev (février 1961) et du Premier vice-président du Conseil des ministres de l'URSS, Anastas Mikoyan, (janvier 1962) au Maroc ont favorisé le renforcement des relations entre les deux pays.

Dans le domaine de la politique étrangère, le Maroc a proclamé le principe de « non-alignement vers les blocs ». Les Marocains ont entrepris de lutter pour la liquidation des bases étrangères militaires, soutenues dans l'arène internationale par l'URSS.

Après l'indépendance, le Maroc a commencé - tentant de trouver un équilibre entre l'Ouest et l'Est - à acheter de l'armement aux pays des deux blocs militaires et politiques existant alors. Les dirigeants soviétiques ont tâché d'utiliser cette opportunité pour la promotion de leur armement et pour le renforcement de la coopération bilatérale avec le Maroc. Des chasseurs à réaction soviétiques furent livrés aux forces aériennes du Maroc en février 1961. Mais la coopération militaro-technique se révéla brève. Après la fin de la guerre d'Algérie, il y eut des discussions entre le Maroc et l'Algérie au sujet de la souveraineté sur certains territoires frontaliers. En octobre 1963, « la guerre des sables » débuta. L'URSS prit le parti de l'Algérie dans ce petit conflit qui eut une influence négative sur le développement des relations soviéto-marocaines.

Une nouvelle étape des relations entre l'URSS et le Maroc débuta au milieu des années 60. L'idée du soutien au « triangle » - France, États-Unis, URSS - selon le projet du roi Hassan II, devait garantir au Maroc une bonne place parmi les pays en voie de développement. Assurément, ce « triangle » n'était pas équilatéral, si l'on considère l'attraction du Maroc pour les pays de l'Ouest. Cependant, le roi ne pouvait pas ignorer le rôle croissant de l'Union soviétique dans la politique et l'économie mondiale, il se rendit donc à Moscou en octobre 1966. Les négociations avec les dirigeants de l'État soviétique donnèrent des résultats féconds dans le domaine du commerce, des relations économiques et culturelles, ainsi que dans la coopération scientifique et technique. Les relations commerciales se développent activement, l'URSS construit une importante série de projets énergétiques et industriels au Maroc. En 1970, le volume des échanges de marchandises entre les deux pays a été multiplié par six par rapport à 1960. Le premier ministre du Maroc, Ahmed Osman, visite Moscou en mars 1978 et signe un accord stratégique sur la coopération économique et commerciale.

Dans les années 60-70, l'Union soviétique apporte également l'investissement nécessaire au développement de la production d'énergie et de l'industrie minière du Maroc. La centrale thermique «Jerrada», le complexe hydro-énergétique « El Mansour El Dhahabi », 200 km de lignes à haute tension pour les transmissions électriques, la centrale hydroélectrique «Moulay Youssef» sont construits grâce à l'aide de l'URSS/Russie. Symbole de la féconde coopération bilatérale, l'ensemble hydro-énergétique « El Ouahda » - un des plus grands chantiers du monde arabe et de l'Afrique (30 % de l'énergie électrique produite au Maroc) - est construit par une compagnie soviétique/russe.

Pendant « la guerre pour la libération » et plus tard dans les années 60-70, une image positive de l'Union soviétique se dessine ; pour de nombreux Marocains, l'URSS est associée à la lutte contre le colonialisme et l'impérialisme, au soutien de la lutte du peuple arabe de la Palestine. L'idée de base, enracinée dans la conscience de n'importe quel Marocain indépendamment de sa position sociale, de son niveau de formation et de ses préférences politiques, est la suivante : « la Russie n'était jamais et ne sera pas l'ennemi pour le monde arabe » (Soukhov, 2009).

Grâce à l'aide soviétique au développement et à la suite de la coopération politique, économique et technique avec l'Algérie et, dans une moindre mesure, la Tunisie, l'image positive de l'URSS se renforce dans ces pays et accroît, par conséquent, l'attrait pour les études dans les universités soviétiques.

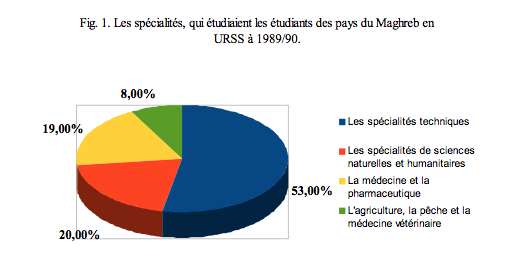

Le choix de la profession

Le choix de la profession future de l'étudiant maghrébin était défini en premier lieu par les besoins en telle ou telle spécialité de l'économie de son pays natal. Ici, nous observons une situation assez semblable pour les trois pays. Les écoles supérieures médicales, agraires, économiques, philologiques et de génie étaient les plus populaires parmi les étudiants des pays du Maghreb. Les spécialités les plus populaires sont la médecine, la pharmacie et la stomatologie, et elles sont réclamées traditionnellement par les étudiants maghrébins, particulièrement par les jeunes filles.

Cet état de fait était induit par l'instabilité politique internationale et intérieure, les conditions naturelles de la région qui manquaient de spécialistes en médecine : les conflits locaux et régionaux, les tremblements de terre, les inondations, les épidémies, avec comme corollaire une énorme partie de la population ayant besoin d'assistance médicale. De plus, on constatait un reflux considérable de ces pays - particulièrement touchés par les crises - des médecins-pratiquants, y compris ceux travaillant dans les hôpitaux, les polycliniques et dans d'autres institutions médicales. Jusqu'à aujourd'hui, la gynécologie, l'oncologie et la cardiologie, activement développées à l'ouest et dans le bloc socialiste, ne sont pas encore très avancées dans les pays de la région.

Parmi les spécialités du génie les plus demandées figurent : la géologie et la reconnaissance des gisements des minéraux, la construction des ponts et des chemins de fer, le génie civil et industriel, les industries technologiques, la production d'énergie et aussi l'architecture. Dans les pays arabes, des programmes précisément élaborés de formation des cadres (tellement importants pour le développement économique moderne) manquent dans les années 60 et 70. Mais en Union soviétique les étudiants algériens, par exemple, acquièrent des connaissances théoriques et des habitudes pratiques pour un travail ultérieur dans les secteurs pétrolier et gazier de l'économie nationale.

L'agriculture représente traditionnellement le segment le plus important de l'économie des pays du Maghreb. Une grande partie de la population travaille dans ce secteur, dont les revenus constituent une part considérable du Produit intérieur brut, bien qu'au total la région ne soit pas riche en sols fertiles, ni en ressources d'eau. La demande en spécialistes-agronomes et en vétérinaires dans ces pays était également presque entièrement satisfaite par l'enseignement supérieur soviétique.

On peut aussi mentionner le journalisme et la philologie parmi les spécialités assez demandées. Les médias servent de principal canal de diffusion des connaissances - à l'exclusion de tout autre. D'autre part, dans les pays arabes le taux de médias par rapport à la population – la quantité de journaux, de chaînes de radio et de télévision pour 1000 personnes – était beaucoup plus faible que le taux moyen dans le monde à la période examinée.

La deuxième spécialité la plus populaire était la philologie. Cette profession offrait notamment aux étudiants étrangers la possibilité d’apprendre le russe et la grande littérature russe, et par la suite, de vivre de l'enseignement, du travail de traducteur ou d'une activité de recherche. Cela concerne particulièrement les lauréats-philologues maghrébins des différentes générations, qui sont des membres respectés de la société et enseignent dans les universités de leur pays.[vi]

Les résultats du traitement des données statistiques indiquent que plus de la moitié des étudiants des pays du Maghreb étudiaient en URSS des spécialités techniques (voir fig. 1).[vii]

Il est important de noter qu'un grand nombre de lauréats marocains des écoles supérieures soviétiques choisissaient une profession en fonction de leurs dispositions personnelles et de leurs passions, ce dont témoignent les réponses aux questions correspondantes du questionnaire diffusé parmi eux par l'auteur.

Le nombre de lauréats marocains des écoles supérieures soviétiques

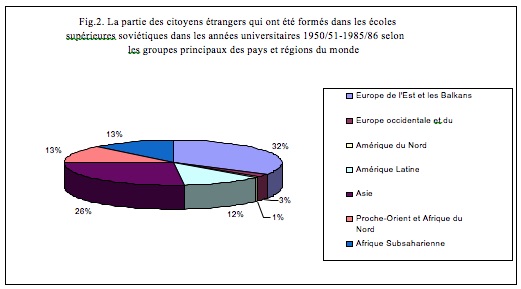

Pendant toute la période examinée (1960-1990), plus de 800 000 personnes se sont formées dans les écoles supérieures soviétiques civiles et militaires, ainsi que dans les écoles spéciales secondaires, les cours divers de préparation, de formation continue, les stages pratiques, etc. Le pic du nombre des étudiants étrangers est atteint en 1989-1990, lorsqu’environ 180 000 citoyens étrangers se forment en URSS (près de 70 % dans les écoles de Russie) dans les différentes filières de formation.

Durant la période soviétique, la plus grande partie des étudiants étrangers étaient originaires des pays socialistes de l'Europe de l'Est (avant tout la RDA, la Bulgarie, la Pologne, la Tchécoslovaquie) et d'Asie (principalement le Vietnam, la Mongolie, la Chine et l'Afghanistan) (voir fig. 2). Puisque les pays d'Afrique du Nord dans les statistiques soviétiques et russes se rapportent toujours aux pays arabes et se confondent avec les données sur le Proche-Orient, nous ne pouvons estimer qu'approximativement la part des étudiants africains dans les écoles supérieures soviétiques à environ 18%.

Malheureusement, il est impossible de faire un compte exact des étudiants des pays du Maghreb ayant reçu un enseignement en Union soviétique, puisque parmi les Algériens, par exemple, prédominaient les cadets militaires et les officiers en formation, dont les données sont tenues secrètes.

Néanmoins, les informations sur les étudiants marocains, puisées dans les informations statistiques du Ministère des Affaires Étrangères et des Ministères de l’enseignement de l'URSS (auquel l'auteur a eu accès dans le cadre de son service), permet d'établir un compte assez exact de leur nombre pour la période de 1956 à 1991. Ainsi, dès l'indépendance du Maroc et jusqu'à la fin de l'existence de l'Union soviétique, plus de 5000 jeunes Marocains ont été formés dans les universités soviétiques.

Ce nombre assez faible de lauréats des écoles supérieures soviétiques - comparé au total des Marocains ayant une instruction supérieure - ne reflète pas le niveau d'importance de ces cadres dans le développement économique du Maroc. Par exemple, au cours d'une conversation avec l'auteur, le gouverneur de la province Rabat-Salé-Zemmour-Zaërs a souligné la haute qualification, la capacité de travail et l'efficacité des lauréats marocains des écoles supérieures soviétiques et russes travaillant dans son administration.[viii]

Les destins professionnels

Pendant plusieurs années l'Union soviétique fut un centre d'attraction pour des millions de gens du monde entier, aspirant à recevoir là-bas une formation, à suivre - comme on disait à l'époque - « l'expérience soviétique avancée » et à l′utiliser pour le bien de leur patrie. En revenant chez eux après leur études à Moscou, Kiev, Minsk, Bakou, Tachkent ou d'autres centres d’enseignement supérieur du pays, les lauréats étrangers ramenaient avec eux plus que la connaissance de la langue et de la culture russes, mais aussi l'amour d'un peuple hospitalier. Bien instruits, ils devenaient des politiques, des hommes d'État, des ingénieurs, des médecins, des acteurs de la science, de la culture et de l'art dans leur pays. De plus, ils gardaient le souvenir de leur jeunesse étudiante, de leurs meilleures années en Union soviétique, et par cela contribuaient au renforcement des liens entre leurs États et le pays qui avait assuré leur formation.

Revenus dans leur pays natal avec un diplôme soviétique, plusieurs lauréats maghrébins ont accédé à des postes de dirigeants haut placés dans les organismes d'État, les ministères, les entreprises publiques et des compagnies privées, ou sont devenus les représentants des États dans d'autres pays, dans des organisations internationales et régionales. Par exemple, l'Association tunisienne des lauréats des universités soviétiques (plus de 450 membres) rassemble des députés, des gouverneurs, des directeurs généraux d'importantes sociétés publiques et privées, des médecins respectés, des collaborateurs de la radio et de la télévision, des professeurs d'université. Plusieurs ingénieurs formés en URSS sont propriétaires de sociétés privées, de bureaux d'études, de construction et d’architecture.

Au Maroc, les lauréats des écoles supérieures soviétiques travaillent principalement dans la fonction publique et dans tous les secteurs de l'économie nationale : l'architecture et la construction, la géodésie et la cartographie, l'agriculture et la pêche, la science et l’enseignement, la santé publique et la production d'énergie. L'auteur connaît également des journalistes, des acteurs culturels, des employés des P.T.T., des pharmaciens et des médecins travaillant dans des sociétés privées.

Malgré l'absence d'obstacles dans le reclassement des lauréats dans la période antérieure à 1992, lorsque l’accord entre l’URSS et le Maroc sur la reconnaissance des diplômes soviétiques de l’enseignement supérieur, signé en 1960, a pris fin en 1992, ces diplômés n'ont pas eu les carrières espérées. À la différence de l'Algérie et de la Tunisie, ils n’ont pas réussi à accéder à des postes élevés.[ix] Cela s'explique par les caractéristiques particulières de la société marocaine, où les principes de solidarité de clan et les clivages sociaux rigides sont forts encore aujourd'hui. On a déjà indiqué plus haut que le contingent des étudiants partis pour des études en Union soviétique grâce aux recommandations de partis «gauches» et d'organisations syndicales, comprenait principalement des représentants des classes pauvres n'appartenant pas aux familles influentes, dont les membres occupent des positions dirigeantes dans le gouvernement et l'économie du Maroc même aujourd'hui.

À notre avis, les destins professionnels des médecins et des pharmaciens ayant étudié en URSS qui travaillent en secteur privé sont les plus gratifiants. Une excellente qualification, l'universalité des connaissances et des pratiques professionnelles les distinguent favorablement des lauréats des écoles supérieures françaises. Ces qualités leur ont assuré une reconnaissance certaine auprès des clients, avec pour conséquence un revenu régulier au-dessus de la moyenne.

* * *

Le départ des étudiants marocains pour des études en URSS dépendait d'un ensemble de facteurs extérieurs et intérieurs. Premièrement, l'URSS accordait des autorisations pour des études supérieures dans n'importe quelle spécialité. Deuxièmement, dans les pays du Maghreb après l'indépendance, il y avait une crise du secteur de l’enseignement. Les capacités des infrastructures universitaires existant à cette époque ne correspondaient pas à la demande apparue dans les sociétés maghrébines.

Le renforcement de l'opposition socialiste et communiste au Maroc - qui, dans les années 60, est entrée en confrontation ouverte avec le gouvernement représentant les intérêts de la grande bourgeoisie nationale - et les répressions qui ont suivi ont contraint une partie des militants du mouvement étudiant à quitter le pays et à partir faire des études en URSS.

L'augmentation du nombre de bourses accordées par l'Union soviétique a permis aux partis d'opposition et aux syndicats durant les années 70 - 80 d'envoyer la jeunesse des classes pauvres non privilégiées de la société marocaine étudier en URSS. (Rappelons qu’il existait alors un accord entre le Maroc et l'URSS sur la reconnaissance des diplômes des universités soviétiques).

Malgré un excellent niveau de formation et l'existence d'une base juridique pour le libre reclassement lors du rapatriement, les diplômés marocains des écoles supérieures soviétiques n'ont en majorité pas réussi à accéder à de hautes fonctions dans les administrations publiques et le secteur économique du pays, comme cela a eu lieu dans plusieurs pays d'Afrique subsaharienne. À notre avis, cela tient en premier lieu au fait qu'ils étaient souvent originaires du milieu des artisans, la classe de la petite bourgeoisie urbaine. D’ailleurs, plusieurs d'entre eux ont indiqué dans les questionnaires des problèmes financiers comme raison du choix des études en URSS.

Et il y avait quand même parmi les lauréats des universités soviétiques des représentants de clans influents, où se recrutent les élites marocaines. Cela est vrai en particulier pour la génération des étudiants partis en Union soviétique dans les années 60. Ils ont occupé des postes de haut niveau dans le cadre de leur activité professionnelle. Mais aujourd'hui cette génération est celle des retraités.

Bibliographie

Soukhov, Nikolay, 2009, Note analytique : l'image de la Russie au Maroc, Maroc. Non publié.

Vermeren, Pierre, 2006, Histoire du Maroc depuis l’indépendance, Paris, La Découverte.

[i] L'étude a été réalisée avec le soutien du RGNF. Projet № 13-21-08001 « Étudiants africains en URSS : la mobilité post-universitaire et le développement de la carrière ».

[ii] Interview d'un lauréat de l'université d'État de Moscou (années d'études : 1969-1976), Enquête de l’auteur, Tanger – Moscou, 2013.

[iii] «Beaucoup de mes camarades ont été arrêtés en 1974, et le fait que j’étais en URSS m’a sauvé la vie». Interview d'un lauréat de l'Université de Moscou, Enquête de l’auteur, Tanger – Moscou, 2013.

[iv] Années de plomb : 1975-1990.

[v] Le nombre de lauréats des écoles supérieures soviétiques en Tunisie est estimé à plus de 2500 personnes.

[vi] Les philologues, lauréats des écoles supérieures soviétiques sont, par exemple, membres de l'Association marocaine des professeurs de russe, coopérant activement avec le Centre Culturel Russe pour la vulgarisation du russe et de la culture russe au Maroc.

[vii] Les résultats des calculs de l'auteur sont basés sur les relevés statistiques du Ministère de l’enseignement de l’URSS.

[viii] De la conversation avec Hassan Amrani, le gouverneur de la province Rabat-Salé-Zemmour-Zaers, Rabat, 2009.

[ix] Selon l'auteur, le poste le plus important auquel a accédé un lauréat de l'enseignement supérieur soviétique au Maroc, est celui de directeur du Théâtre National, mais le poste avec le plus de responsabilités est celui de directeur régional de l’Office National d’Électricité.

Russian Women and the Sharia. Drama in Women's Quarters

According to the data of the Department of Consular Service of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation, most women – citizens of the former USSR or the new independent states in the post-Soviet era, who are married to citizens of African countries, are Russian by nationality. As to the places of their settlement on the African continent, Russian women live in 52 states of Africa. About 60 percent of them are the wives of men from North Africa – the main Islamic belt of the African continent.1 This circumstance prompted the author of this article to acquaint the reader with certain specific features of the social and legal practices of the Magrib countries in relation to foreign citizens marrying citizens of North African states.

According to the data of the Department of Consular Service of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation, most women – citizens of the former USSR or the new independent states in the post-Soviet era, who are married to citizens of African countries, are Russian by nationality. As to the places of their settlement on the African continent, Russian women live in 52 states of Africa. About 60 percent of them are the wives of men from North Africa – the main Islamic belt of the African continent.1 This circumstance prompted the author of this article to acquaint the reader with certain specific features of the social and legal practices of the Magrib countries in relation to foreign citizens marrying citizens of North African states.

In this connection we are interested, first and foremost, in the acculturation problem through marriage in modern Islam, particularly, the problem of the adaptation of Russian women in the Islamic world, if not their participation in religious rites then their everyday life in the Moslem medium.

Touching on the socio-cultural aspect of the problem (the legal elements of the Sharia have thoroughly been analyzed by many scholars of the Orient, especially the Arab East2), I shall note that, according to Moslem concepts, woman is not an independent creature, but one living in order to belong to man. Such discrimination (from the European point of view) begins from the very birth of a girl – the fact negative in Islamic perception. Later, it is manifested in a different approach to the upbringing of boys and girls, and also during all periods of woman’s life. The main task of her existence is marriage, the birth and upbringing of children, and her main ideology is unconditional submission to the husband.

In contrast, boys are taught from the very first years to think of and feel their superiority, their future role as masters, continuers of the family, who should not only support women materially, but also act as intermediaries in their relations with the outer world.

One of the most conservative principles of the Moslem social doctrine in its attitude to women is the institution of seclusion. This principle should be strictly observed by the family and the outward attribute of it is the veil, or hidjab. This is a subject of continuing discussions between the supporters of the preservation of traditional Islamic values, on the one hand, and modernists, on the other, as well as between various scholars and public and political figures. The married woman in the Islamic family often becomes a privatized object of private life, deprived of personal contacts with the surrounding world, strictly controlled by man and fully dependent on his will.

Traditional Islamic Model of Marriage and Family Relations

An interesting tendency was observed in Côte d’Ivoire in the mid-1990s, which was manifested in the relations between indigenous black men and young Lebanese women living in the country, which some of the local mass media regarded racist. During the past several decades people from the Middle East have settled in Cote d’Ivoire and neighbouring countries, however, mixed marriages between Lebanese and Africans have been few and far between. And it was not due to racialism. It was because the Oriental traditions were too strong in the consciousness and everyday life of the fathers and brothers of potential brides, who strictly controlled and guarded them, keeping them untouched before marriage. Marriage and sex relations in Cote d’Ivoire, especially in its capital Abidjan, were many and varied. Polygamy, levirate, premarital relations, etc. were rather widespread, and this was why there were cases of fist fights between relatives and the claimant, as well as direct imprisonment of women within the four walls of their family homes.

The private life of a woman, including sex life, in Moslem interpretation is based on such Koran premises as honour, chastity and modesty, which are a must and form the basis of the strict control of society over its members. Let us turn to an interview given by I. Abramova, which illustrates attempts to violate certain premises of the Koran undertaken by Russian wives.

“Relations in the family went from bad to worse. After all, they were educated girls from Moscow used to a different way of life. But they had to stay at home all day long and do household chores. They had no right to work. That is, they had that right, as far as I know, but they had to have their husbands’ permission, which they, naturally, did not give. Such life was not to their liking. Then quarrels, even scandals began. They tried to defend their rights, but were told that there were no rights for them, and that they had to obey the husband and mother-in-law.”

The system of traditional Moslem education and upbringing demands that woman should observe the rules of social behavior, such as lower her eyelids when meeting a man, hide not only the head and body, but also decorations under garment, move noiselessly, not leave home without permission, perform ritual ablutions, and do many more things, according to the Sura “Women” (IV) of the Koran. As to the intimate relations (no matter how varied customs and habits might be in the different social spheres of the Islamic world), according to the Koran and the official position of most societies of this cultural-religious zone, all questions pertaining to sex can only be resolved in marriage. Naturally, the Koran regulates sex relations and forbids adultery and incest. It is indicative that the culture of hidjab does not pacify men sexually. On the contrary, experts emphasize that deprived of the opportunity to see the faces and bodies of women, Moslem men feel greater tension and are more aggressive sexually than men representing cultures which do not have such strict bans concerning women.3

The Magrib expert A. Buhdiba points out that during the past centuries various social sections have evolved their own specific attitude to the traditional Islamic model of the ethics of relations between men and women. True, any society (and the Islamic world is no exception) has a great variety of sex relations. The Magrib tradition denounces this, society closes its eyes to it, but in actual fact, all these questions are surrounded by the wall of public silence. 4

Finally, it should be admitted that young people in the Islamic regions of Africa (as in other cultural-historical zones of the continent, for that matter) break through the bounds of this single and generally accepted model and more insistently orient themselves to other examples of marriage-sex relations, primarily, European ones.

On the other hand, it is precisely the ideas of chastity and honour based on the Koran that continue to shape and influence the outlook of the new generation of Moslems, form the basic element of their upbringing and education, and realize the intricate mutual connection between the socio-cultural innovations and the value-cultural traditions of definite social groups – ethnoses, classes and generations. Our compatriot (her name is Lyuba) notes:

“One Somali man says that my marriage with Said (the first husband of Lyuba. Now she is married again to a Somali) is unhappy because Christianity and Islam are different cultures and cannot be compatible…However, women’s education raises their status and freedom in Somalia, it seems to me. This is why they forgive me much…”

Let us examine the problem in its civil and legal aspect. As is known, the marriage and family codes in African countries are many and varied. On the one hand, they were formed under the influence of the local historical and cultural tradition and the system of common law connected with it, and on the other, they were (and still are) influenced by the European legal standards, thus presenting an intricate (sometimes conflicting) mixture of the common law, the religious marriage and family system, and the modern state legislation.5 The standards of behaviour and morality of people are often determined by a traditional religious-legal system, which continues to play a major role in marriage and family relations, including those with people of other religions. It is especially well-pronounced in the North African region, in the countries with the firm Islamic tradition, where the views on marriage, the family and family life are strictly regimented by the Moslem dogmas, law and ethics contained in the Koran. Besides, most Russian women marrying men from the African countries of the Islamic belt do not know Africa,6 they are completely ignorant about Moslem legal culture, in general, and about the Sharia as the universal code of behavior, both religious and secular, which is especially strict in the system of marriage and family relations and in the questions of succession. We shall dwell on the problem using the example of the Islamic Republic of Mauritania and the Tunisian Republic.

Mixed Marriages and Traditional Religious-Legal System

Although the Sharia in Mauritania became the basis of its legislation comparatively recently (in the early 1980s), its standards regulate practically all spheres of the public, family and private life of the country’s citizens.7 Along with this, the common law (adat)8 plays an important role in the family relations of people in Mauritania. The wedding ceremony of Mauritanian Moslems is not as solemn as Russian women are used to. This is how it is described by one of our respondents, who lived in the city of Nouakchott:

“The ceremony is very modest. Marriage is registered either at home or in a mosque in the presence of close relatives. The written document is not necessary: suffice it to have two male witnesses, or one male and two female witnesses. Their presence at the ceremony is simply formal when the parents of the groom pay engagement money to the father of the bride, and the priest reads certain Suras of the Koran and repeats the terms of the marriage contract three times…If religious marriage is concluded between a Moslem man and a Christian woman, their marriage contract stipulates the minimal engagement money, or there can be no contract at all. Incidentally, when marriage is concluded between a Moslem man and a Moslem woman, witnesses must be Moslem, too. Jews or Christians can be witnesses in exceptional cases, when a Moslem marries a daughter of a ‘ man of Scripture’, that is, Christian or Jewish.”9

As to mixed marriages, they occupy a special place in the Islamic legal system. The Koran and other fundamental Islamic documents concretely determine the conditions permitting marriage with members of other religions. Referring to numerous quotations from the Koran devoted to marriage, directly or indirectly, which divide mankind into the believers and the infidels and define the boundaries between the “pure” and the “impure”, separating Moslems from non-Moslems, the well-known French scholar of Islam, M. Arcoun, notes that already in the early epoch of the Koran, people knew that legitimacy of each marriage was connected with the level of religious “purity.”10 It should be noted that the appearance of bans and permissions in the legal system regulating mixed marriages was, as a rule, connected with concrete historical conditions. In some cases Islam categorically forbids marriages between members of other religions, and in other cases, on the contrary, it supports them. Islam is absolutely intolerant toward concluding marriages between Moslems and heathens (2: 220-221).

The Sharia has a different attitude to marriages between Moslems and persons of Christian and Judaic religions. When concluding marriage with women of these religions, the Moslem should observe the same conditions as in the Moslem marriage. At the same time, Moslem marriage with a Christian or Jewish woman is permissible only if the latter are “women of Scripture.” Marriage of a Moslem woman to a Christian or Jew is out of the question. In our case there are no collisions, because most mixed marriages are between African Moslem men and Russian Christian (or atheist) women. If a Moslem woman dares commit such apostate act, she may be put to prison to enable her “to think of her fallacy.” This happens because (as local experts on the Sharia standards assert) man with his unlimited power and undisputed authority in the family will be able to turn his wife to his faith. Such “religious evolution” of the infidel is approved by Moslem morality which gives her absolution.

For this very reason Islam is absolutely intolerant to marriages between Moslem women and persons of alien faiths. Finally, marriages with atheists are banned altogether. Thus, marriage unions between Mauritanians and Soviet/Russian women concluded in the former USSR or the present Russian Federation have no legal status on the territory of Mauritania (even if they are sealed in full conformity with the Soviet/Russian law), they are not registered officially and are regarded as cohabitation. True, by their national character Mauritanians are distinguished by religious tolerance, this is why public opinion in the country, as a rule, recognizes Russian-Mauritanian mixed marriages de facto.

Quite a few works are devoted to the specific features of Moslem marriage and the family, the history and traditions of the social behaviour of men and women in the world of Islam, the way of life, morality and psychology and the rules of behavior of married woman in Moslem society.11 It should be borne in mind that polygamy in its most widespread form – polygyny – is a most typical feature of Moslem marriage. The Koran allows Moslems to be married to four women (the Koran 4:3). This premise is considered to be the sacred foundation of polygamous Moslem marriage. Although in a modern Mauritanian family (and in a North African family, for that matter) this privilege is not used by all men ( because of the influence of the democratically-minded forces who denounce polygyny among officials , and also due to purely economic reasons, because far from all men can provide the necessary means to several women simultaneously.) At the same time the social doctrine of Islam, which institutionalized the inequality of sexes in Moslem family, laid the foundation for the dependent position of woman with regard to her husband in case of divorce. It is here that male “autocracy” is revealed in its true form.

Divorce “Moslem Style” (Mauritania)

Perhaps, the principal feature of the Sharia divorce is that its initiative comes practically always from the husband. Divorce is considered a unilateral action which is usually started by man. The latter enjoys unrestricted rights in divorce. For instance, he can divorce any of his wives as he pleases at any time without giving any reason. (There have been such cases in the compounds of our compatriots who were married to North African Moslems and lived in African countries permanently.12 The consequences of Moslem divorce for woman are exceptionally hard, both morally and economically. To say nothing of the difficulties she will encounter if she wants to build a new family, especially if she is a foreigner.

The divorce procedure also grants privileges to man. According to a Russian woman who was a party to a divorce, the husband has only to say three times “You’re my wife no more”, and divorce comes into effect. In other words, an oral statement is enough to break up marriage.

There are many nuances in the divorce procedure in the Moslem world, but all of them have a pronounced anti-feminist character. We should also note that Moslem legislation recognizes certain reasons which allow woman to come out with the initiative of divorce. Among them are apostasy, prolonged absence, or certain physical defects concealed before marriage.

In this connection we’d like to turn attention to several interesting aspects which are part of Mauritanian Moslem law and are directly connected with the discussed case of Afro-Russian marriage.

Our compatriots who have registered their marriage with Mauritanians in their native country sometimes use the premise of the Sharia forbidding Moslem to conclude marriage with an atheist in their own interests. In the situation when they themselves wish to divorce the citizen of Mauritania, they declare in court that they concealed their atheistic convictions when concluding marriage, after which the judge immediately pronounces marriage null and void. (But even in this case the children born of this marriage remain with their father and are regarded citizens of Mauritania.) Nevertheless, the Mauritanian still retains a loophole: he may apply to the secular court (Mauritania has double legislation) which may pass a ruling on the basis of the standards of the French secular law.

Property matters in divorce cases of a foreign woman and a Mauritanian citizen are settled on the basis of the Sharia. There are specific features of the status of a Russian woman who concluded marriage with a Mauritanian in her native country, which is legally invalid in Mauritania. She has certain privileges in divorce as compared with a Moslem woman. The point is that in breaking up Moslem (religious) marriage the divorced woman has no right to claim any part of the common property, except her personal savings, incomes and presents from the husband. In case of marriage of a Russian woman to a Mauritanian concluded in Russia, the Moslem court, not recognizing this marriage legal and regarding it as a form of cohabitation by mutual consent (partnership), recognizes the woman’s right to common property. The examination of such a case in the Mauritanian court is considered as the examination of a civil property suit and is not regarded as divorce. If the woman succeeds in proving the fact that she had incomes of her own and gave them over to her companion, or that some property was acquired by her money, the court may rule to give her a part of that property or pay certain compensation. After divorce foreign women may continue to stay in Mauritania for quite a long time using their national passport, which should be registered with the police every year. Foreign women can obtain Mauritanian citizenship after five years of staying in the republic.

The Code of Personal Status and Women’s Rights in Tunisia

The spheres of law regulating marriage and family relations in Tunisia bear a noticeable imprint of traditional Moslem ideas and premises of the Koran, although the problems of the legal position of women, equality of their rights (just as the women’s problem as a whole), in contrast to other Arab countries in North Africa, have developed more favourably there. These specific features should be taken into account when examining the question of the legal position of Russian women married to Tunisians.

The Code of personal status adopted in 195613 laid down the basic principles of the emancipation of Tunisian women at a state level. The personal inviolability and human dignity of women it proclaimed were later bolstered by a whole range of measures, among which were a ban on polygamy (any violation of the ban was punishable by law); the establishment of legal divorce given by husband to wife, and the official right to divorce given to both; permission to the mother to have the right to custody over minor children in an event of the father’s death, etc. The Code of personal status existing for half a century has constantly been revised and amended in accordance with the country’s legislation.

Tunisian legislation, regulating the legal status of women, envisages six civil states of a woman in her life: woman as bride, as wife, as mother, as divorcee, as guardian, and as worker. We shall deal with those of their states which can be applied to a foreigner married to a Tunisian.

Leaving aside the general Tunisian standards of marriage procedure (they are much like those in Mauritania), we shall note that by Moslem law the suitor must make a “marriage settlement (Mehar)” on the bride. This condition is contained in the Code of personal status (Article 12, revised version), although the size of the “settlement” is not agreed upon (it can even be symbolic), but it is always considered the private property of the wife only to be paid to her in case of a divorce (the “private property of the wife”, according to Tunisian law, includes presents and incomes from hired work or business, which remain in her possession in case of divorce.)14

As to the rights and duties of foreign woman, they are determined by Article 23 of the Code of personal status, and practically all its premises have been taken from the Koran. Despite the fact that the new version of that article formally grants the wife equal rights with the husband15 (the previous version of that article (para 3) made it incumbent on the wife to obey her husband in everything), in the event of legal collisions, for instance, a Moslem marrying a non-Moslem woman, or a suit being examined in court, the Sharia plays a considerable role as before.

Brought up and educated in the spirit of the socialist equality of rights of men and women, Russian wives of North African Moslems cannot get used to the legally endorsed supremacy of the husband and submission to him as the head of the family, which inevitably results in family collisions often leading to divorce.16 However, as the practice of Russian consular offices in those countries shows, there is a possibility to adjust and balance such situations. For example, Article 11 of the Code of personal status envisages that marrying persons may conclude, along with marriage settlement, contracts of other types, conditioning certain specific features of the given marriage. Unfortunately, this article is used rather seldom and not always correctly. Although there is a quite reasonable condition (which is essential from the point of view of the legal position of the foreign wife) determining temporary employment, place of residence, joint property, etc. For instance, the Tunisian husband, as the head of the family, has the right to prevent his wife from working. On the basis of the above-mentioned article it could have been possible to fix her “right to work” in marriage settlement or supplements to it. Besides, a step forward has been made by the Tunisian legislation in the sphere of economic and social rights. The Code of duties and contracts broadens the Sharia framework regulating the rights of women and grants them the right to sign contracts and agreements in the sphere of property relations, buy, sell and dispose of their property.

The same can be said about the place of residence which is also chosen by the husband. Then again, a foreign wife, who does not want to follow her husband to Tunisia can state her wish beforehand, or choose the concrete place to live in Tunisia. Thus, there is a possibility to fix legally certain liabilities of the husband with regard to his wife.17

We should also note that on the whole the local legislation, while regulating the legal rights of a divorced woman (incidentally, no distinctions are drawn between a Tunisian woman and a woman-citizen of another country), regards the latter in two positions – the divorcee and the divorcee with the right of guardianship. We’d like to turn attention to several circumstances connected with the fate of the children after divorce in a mixed family.

Prior to 1966 there was the rule according to which priority right with regard to children was given to the mother, irrespective of whether she was Tunisian or foreign. At present local legal practice is based on a rather vague term “the interests of the child.” Thus, in case of divorce, guardianship is given to one of the parents or a third person, with due regard for the interests of the child. But if the mother takes guardianship, she bears full responsibility for the upbringing and education of the child, his or her health, rest and recreation, travel, and financial expenses (this is stated in the new Article 67 of the Code of personal status which now gives the mother some of the rights or the full right of guardianship, depending on the real state of affairs.)18 This is why in a mixed marriage, where the legal and economic status of woman, as a rule, is rather unstable, the question of children staying with one of the parents after divorce is settled in favour of the Tunisian father. The main argument of the latter is the assertion that the mother will take the children back home, depriving him of guardianship, that is, of the parental rights to participate in the upbringing of the children. At the same time, in a number of cases of divorce, there may be a positive decision in favour of mothers-foreigners (Soviet/Russian citizens), who had the Tunisian national passport. Considerable role was played by the personal qualities of the woman, her ability to keep her temper in bounds and act properly, to converse in a foreign language, as well as her profession or trade, her living quarters, etc.

In general, it should be noted that when we talk of easy divorce according to the Sharia law, it does not mean that this can widely be applied to all Moslem countries. There are many reasons for this connected with the specific features of the historical and cultural traditions, and also those of an economic character. Although the Sharia formally places all Moslem men in a similar legal position, divorce is a rare phenomenon among the poor sections of the population, inasmuch as it is rather expensive to turn a legal possibility into reality.

As to the minor children left after the husband’s death, the modern Tunisian legislation envisages that their mother is their guardian with all ensuing rights (Article 154 of the Code of personal status), irrespective of whether she is Tunisian or foreign. This article went into force in 1981. Before that guardianship was given over to the nearest heir-man. According to the modern Tunisian legislation, in 1993 the divorced mother received the right of guardianship of her child. Previously, according to Moslem tradition, this right was granted exclusively to men (Article 5 of the Code of personal status).

Examining the new laws and amendments called upon to strengthen the legal status of woman (including foreign woman) in the system of marriage and family relations, it should be noted that despite the efforts of the government, their implementation is accompanied by great difficulties. In general, the practical solution of all these questions, although they have many specific features and nuances, largely depends, as before, on the position taken by the husband himself, or his relatives.

Finally, it would be expedient to mention changes in the attitude of Moslems themselves toward mixed marriages. In the view of M. Arcoun, mixed marriage leads not only to psychological and cultural perturbations. Based on the family cell alone represented by husband and wife and their children, it destroys the patriarchal family as such, which needs broader framework of social solidarity, which is quite effective and cannot be replaced by any modern institutions of social security (in the West such bodies are often publicly recognized as unfit, useless and even harmful, for instance, in social welfare in old age; old people often find themselves outcast and become marginalized.)

Thus, the modern problems of mixed marriages are based not so much on religious and racial grounds, as on weightier moral, psychological and cultural foundations.

First published in Asia and Africa Today, 2007, No 1, pp. 47-54.

*****

Not claiming the universal character of the maxim “forewarned is forearmed”, we, nevertheless, think that it would be quite useful for the new generations of Russian women who choose husbands from among people in the Islamic world, to acquaint themselves with this information.

______________

Notes:

1. We emphasize that this concerns only the Islamic belt of the continent. In reality, the total number of Moslems in Africa comprised over 40 percent of the entire population of Africa by the early 1990s. Forty-six percent of them lived in North and Northeast Africa, about 18 percent in East Africa, 32 percent in West Africa, and about three percent in South and Central Africa. The largest Moslem communities are in Egypt (over 90 percent of the entire population of the country), Nigeria (46 percent), Algeria (99.6 percent), Morocco (99 percent), Tunisia (98.7 percent), Sudan (about 73 percent), Ethiopia (no less than 50 percent), Guinea (over 80 percent), Senegal (80 percent), Tanzania (over 25 percent of the entire population), Somalia (almost 100 percent), Libya (about 90 percent). For more details see: Африка. Энциклопедический словарь. Т.1. М., 1986, с. 590-591 (Africa:Encyclopaedic Reference Book.Vol 1, M., 1986, pp. 590-591).

2. See, for example:Гилязутдинова Р.Х. Юридическая природа мусульманского права // Шариат: теория и практика. Материалы Межрегиональной научно-практической конференции. Уфа, 2000; она же: Дискриминация женщин по мусульманскому праву // Актуальные проблемы теории права и государства и экологического права. М., 2000; Сюкияйнен Л.Р. Шариат и мусульманская правовая культура. М., 1997; он же: Найдется ли шариату место в российской правовой системе // Ислам на постсоветском пространстве: взгляд изнутри. М., 2001 (Gilyazutdinova, R.Kh. “Legal Nature of Moslem Law//The Sharia: Theory and Practice. Abstracts of the Interregional Scientific Conference.” Ufa, 2000; The same author: “Discrimination of Women by Moslem Law” // Practical Problems of the Theory of Law and the State and Ecological Law M., 2000; Syukiyainen, L.R. “The Sharia and Moslem Legal Culture.” M., 1997; The same author: “Will the Sharia Find Its Place in the Russian Legal System?” // Islam in the Post-Soviet Era: View from Inside. M., 2001). Accepting the system of definitions of the latter presented by the above-mentioned authors, including the cultural-legal incorrectness of identifying Moslem law with the Sharia, which is, above all, the religious conceptual basis of Moslem law, we shall use the terms currently practiced by consular offices and organizations in charge of our fellow-compatriots permanently living in African countries.

3. Мехти Ниязи. Мусульманская женщина: сложные последствия наложенных ограничений // Gross Vita. Вып. 1 (Mehti Niyazi. “Moslem Woman: Difficult Consequences of Restrictions” // Gross Vita. No 1) – This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

4. Восток (Vostok). 1992, No 1, p. 61.

5. Синицына И.Е. Обычай и обычное право в современной Африке. М., 1978; она же. Человек и семья в Африке (По материалам обычного права). М., 1989; Энтин Л.М. Роль государства в общественном развитии стран Африки. - В: "Общество и государство в Тропической Африке". М., 1980; Иорданский В.Б. Хаос и гармония. М., 1982; Право в развивающихся странах: традиции и заимствования. М., 1985; Сюкияйнен Л.Р. Мусульманское право. Вопросы теории и практики. М., 1986. (Sinitsyna, I.E. “Habit and Common Law in Modern Africa.” M., 1978; The same author: “Man and the Family in Africa (On Materials of Common Law).” M., 1989; Entin, L.M. “The Role of the State in the Social Development of African Countries” // “Society and the State in Tropical Africa”. M., 1980; Iordansky, V.B. “Chaos and Harmony.” M., 1982; Law in Developing Countries: Traditions and Borrowings. M., 1985; Syukiyainen, L.R. “Moslem Law. Questions of Theory and Practice.” M., 1986). Also: “Le Droit de la famille en Afrique Noire et a Madagascar.” P., 1968.

6. “Marriage as a Way Out” to Other Cultural-Religious Areas Is Not Typical, as a Rule, of Moslem Women.

7. For a number of years there have been attempts in Mauritania to evolve a civil code of marriage and the family, always obstructed by the Moslem clergy. Thus a decision was adopted by the Politburo of the ruling party of the Mauritanian people in the latter half of the 1970s on introducing the Sharia as a code of legislative and ethical principles in the country’s state and public life.

8. There have always been various traditions and customs in the Islamic world. In this connection the question of the correlation of the Sharia and the adat (the term meaning customs, habits and traditions which regulate, along with the Sharia the way of life of the Moslems of one or another region.) has become quite important. However, the Sharia principles and standards are considered mandatory and should be strictly adhered to, and they are above all rules of behavior, including the adat. This plays a major role in the regulation of marriage and family relations with persons of other religions. Moslem legislation allows people to be guided by the adat, provided it does not run counter to the Sharia, however, in the real life of many Moslem nations customs and habits continue to exist, which do not fully coincide with Islamic precepts, and sometimes, even contradict them. Islamic scholars point out that the term adat is used to denote the common law of Islamic people. The system of the rules of behavior, which is a combination of local customs and certain standards of the Sharia, can be termed the adat law, whose certain premises are recognized by courts, and sometimes form the foundation of the marriage and family legislation. (For more details see:Сюкияйнен Л.Р. Мусульманское право. Вопросы теории и практики. М., 1986).Syukiyainen, L.R. “Moslem Law. Questions of Theory and Practice.” M., 1986.) The adat as a system of social standards based on local customs of non-Islamic origin is quite widespread in a number of African regions to this day. Most of these customs and habits took shape back at the time of the existence of tribal family relations and paganism. Even the introduction and establishment of Islam have not led to their complete replacement with the Sharia.

9. From the personal archives of the author. Letter from Mrs. A.M. in Nouakchott, September 20, 1997.

10 Аркун М. Смешанные брачные союзы в мусульманской среде // Восток. (Arcoun, M. “Mixed Marriages in the Moslem Medium” // Vostok). 2001, No 6, pp. 131-132.

11 See, for example: Сиверцева Т.Ф. Семья в развивающихся странах Востока (социально-демографический анализ). М., 1985; она же: Модернизация и ее влияние на семью на Востоке // Взаимодействие и взаимовлияние цивилизаций и культур на Востоке. М., 1988; она же: Страны Востока: модель рождаемости. М., 1997; Бухдиба А. Магрибинское общество и проблемы секса // Восток, 1992, № 1; Пономаренко Л.В. Ислам в общественно-политической и культурной жизни Франции и государств Северной и Западной Африки // Вопросы истории, 1998, № 9; Аркун М. Смешанные брачные союзы…; (Sivertseva, T.F. “The Family in the Developing Countries of the East (socio-demographic analysis).” M., 1985; by the same author: “Modernization and Its Influence on the Family in the East” // Interaction and Mutual Influence of Civilizations and Cultures in the East. M., 1998; by the same author: “Countries of the East: Model of Birth Rate.” M., 1997; Buhdiba, A. “Magrib Society and Problems of Sex” // Vostok, 1992, No 1; Ponomarenko, L.V. “Islam in the Public, Political and Cultural Life of France and the States of North and West Africa” // Problems of History, 1998, No 9; Arcoun, M. “Mixed Marriages…”); Mernissi, F.“Sexe, Idéologie, Islam.” P., 1982; “Women and Gender in Islam. Historical Roots of a Modern Debate.” Yale Iniv. Press, 1992; Tersigni, S.“Foulard et Frontière: le cas des étudiantes musulmanes à l’Université Paris” // Cahiers de l/URMIS unité de recherché migrations et société. P., 1998, No 4, etc.

12. Information from the Soviet Embassy in Sudan of April 6, 1987, to the head of the Consular Department of the USSR Foreign Ministry; documents from the Soviet Embassy in Tanzania of February 14, 1978 to the head of the Consular Department of the USSR Foreign Ministry, to the Foreign Ministry of Ukraine, to the Personnel Department of the USSR Ministry of Defence, etc.

13. Personal status is a section of Moslem law regulating the major sphere of the legal position of Moslems. It includes marriage, family and hereditary property relations, mutual obligations of relatives, guardianship, and some other problems. Moslems pay much attention to them because most premises on personal status are contained in the Koran and Sunna.

14. The former President of Tunisia Habib Bourgiba tried to include in legislation in 1980 the premise declaring that all property (personal and real) acquired by one of the spouses becomes the common property of the family. However, his attempt ran against the strong opposition of traditionalists. A year later a so-called life-long alimony was introduced to compensate women for moral and material loss in divorce, the size of which was determined on the basis of the “average living standard of the family.” The alimony could be replaced by a lump sum if the divorced woman so wished.

15. The revised Article 23 of the Code of personal status says that both husband and wife should treat each other with love, kindness and respect, avoiding negative impacts on each other. They should perform their marital duties in conformity with traditions and customs. They should run their household and bring up the children properly. The husband as the head of the family should support his wife and children in every way, and the wife should also contribute to the welfare of the family if she has means to do this (Najet Zonaoui Brahmi. Des amendements et des dispositions nouvelles. Une volonte egalitaire, 1997, No 12, pp. 35-36.)

16.Consular data show that most divorces take place in the families in which the wives are Russian (Ukranian and Belorussian); there can practically be no divorces in the families where the wives are of Central Asian or Transcaucasian origin, who are fewer and far between among those living in Tunisia permanently today.

17. Document of the USSR Embassy in Tunisia “On Organizing Registration Office in Tunisia” of March 13, 1990; Document of the USSR Embassy in Tunisia on “Certain Aspects of Legal Position of Foreign Citizens Married to Tunisians” of May 21, 1991.

18. In 1995 the government of Tunisia published the law No 65/93 and set up special Guarantee Fund for paying alimony and bonuses to divorced wives and their children. This Fund is under the National Insurance Fund (CNSS) and draws its means from the state budget, alimonies and pensions on divorce, interest, and fines, incomes from capital invested by the Fund, as well as donations from private individuals.