Can the new UN chief help resolve the Syrian crisis?

United States has officially announced the suspension of diplomatic cooperation with Russia on Syria. That brings to an end coordination of efforts to counter terrorism and also the ceasefire that was in place.

United States has officially announced the suspension of diplomatic cooperation with Russia on Syria. That brings to an end coordination of efforts to counter terrorism and also the ceasefire that was in place.

Basically, it seems, Washington failed to distinguish between Jabhat an-Nusra and the so-called moderate rebels. Russia, on the other hand, has failed to fulfill its commitments. Irre-spective of whether this is due to lack of influence on Damascus, Russia has driven itself to a narrow corridor with not so well thought out policy. It seemed to be following Napoleon’s logic of jumping into the fray and then figuring out what to do next.

There have been miscalculations, difference over stated and real objectives in the Syrian conflict while the geopolitical intrigues and mistrust have brought about the paralysis of the entire political process.

The UN has failed in its mission due to many reasons including tension between global players such as Russia and the US. This has been exacerbated by the opposition’s lack of be-lief in any talks with Damascus and the UN’s failure to invoke the international system.

A new round of talks was scheduled to be held in the end of August but is now unlikely in the near future. Under these circumstances, which are pushing the world to the brink of a global conflict, we need more than ever the strong a truly powerful United Nations.

The election of the new Secretary General of the UN deserves special attention. Ban Ki-moon’s successor will not only inherit unresolved conflicts but also the full new pack of rapidly developing threats coming from two superpowers.

The problem is that while promoting their candidate countries are guided not by the desire to strengthen the UN as an institution, to enable it to tackle global threats, but instead fol-low their own interests. The US seems to be interested in a female candidate to occupy the chair, while Russia promotes Eastern European candidate.

The leader of the UN should have enough courage to push the entire organization toward reforms. For this the UN needs a very determined and resolute person who is ready to take risk and bear the responsibility for each step taken and its consequences. The new UN Sec-retary General should be truly independent and try to return to the UN its damaged reputa-tion.

The new Secretary General should also be as active as possible in the media, competing with the major world leaders in popularity. Theoretically he or she should be a well-known per-sonality with an unblemished reputation and enjoy universal esteem. The UN needs a leader that helps the world body truly serve the cause of peace, not interests of any player or a group of players.

The problem is that among the candidates to the Secretary General there is no figure that would correspond to all of these parameters. It is likely that the UN will continue to face the same challenges, which means it will continue to become more and more irrelevant and far removed from the global agenda leaving crisis resolution to the US and its allies. Russia, on the other hand, will try to bring debates back to the UN, trying to use the advantages of the UN in its current form; based on the same mechanism as in 1945.

The debates over comprehensive UN reforms have continued for too long and will not change no matter who is elected. However, it is the right moment to fully realize the fundamental importance of the UN.

The conflict seems to have reached a dead-end in Syria with all sides having little under-standing of what to do next. What is clear is that the country will be generously fueled with arms. The US and Russia tensions and mutual accusation will continue to rise.

Even as diplomacy stalls, Russia continues to deploy its advanced anti-missile and anti-aircraft system SA-23 Gladiator and bombers. This time the air defense system is deployed not just to protect Russia’s contingency, but Damascus and the ruling regime even as the already deployed S-400’s purpose is changing as well.

Russia will try all possible means to prevent the repeat of Libyan scenario in Syria. The sig-nificant build-up of weapons in Syria and the deepening rivalry enhances the possibility of the Russian collision with coalition forces in the air.

To prevent the worst case scenario, we need the strong and mighty UN, to convincingly en-courage the parties involved to understand the dangerously developing situation and act to ensure peaceful coexistence. Otherwise it seems like we are all doomed.

Article published in Al Arabiya English

https://english.alarabiya.net/en/views/news/middle-east/2016/10/05/Can-new-UN-Secretary-General-help-resolve-the-Syrian-crisis-.html

How the US Armed-up Syrian Jihadists by Alastair Crooke

The West blames Russia for the bloody mess in Syria, but U.S. Special Forces saw close up how the chaotic U.S. policy of aiding Syrian jihadists enabled Al Qaeda and ISIS to rip Syria apart, explains ex-British diplomat Alastair Crooke.

“No one on the ground believes in this mission or this effort”, a former Green Beret writes of America’s covert and clandestine programs to train and arm Syrian insurgents, “they know we are just training the next generation of jihadis, so they are sabotaging it by saying, ‘Fuck it, who cares?’”. “I don’t want to be responsible for Nusra guys saying they were trained by Americans,” the Green Beret added.

In a detailed report, US Special Forces Sabotage White House Policy gone Disastrously Wrong with Covert Ops in Syria, Jack Murphy, himself a former Green Beret (U.S. Special Forces), recounts a former CIA officer having told him how the “the Syria covert action program is [CIA Director John] Brennan’s baby …Brennan was the one who breathed life into the Syrian Task Force … John Brennan loved that regime-change bullshit.”

In gist, Murphy tells the story of U.S. Special Forces under one Presidential authority, arming Syrian anti-ISIS forces, whilst the CIA, obsessed with overthrowing President Bashar al-Assad, and operating under a separate Presidential authority, conducts a separate and parallel program to arm anti-Assad insurgents.

Murphy’s report makes clear the CIA disdain for combatting ISIS (though this altered somewhat with the beheading of American journalist James Foley in August 2014): “With the CIA wanting little to do with anti-ISIS operations as they are focused on bringing down the Assad regime, the agency kicked the can over to 5th Special Forces Group. Basing themselves out of Jordan and Turkey” — operating under “military activities” authority, rather than under the CIA’s coveted Title 50 covert action authority.

The “untold story,” Murphy writes, is one of abuse, as well as bureaucratic infighting, which has only contributed to perpetuating the Syrian conflict.

But it is not the “turf wars,” nor the “abuse and waste,” which occupies the central part of Murphy’s long report, that truly matters; nor even the contradictory and self-defeating nature of U.S. objectives pursued. Rather, the report tells us quite plainly why the attempted ceasefires have failed (although this is not explicitly treated in the analysis), and it helps explain why parts of the U.S. Administration (Defense Secretary Ashton Carter and CIA Director Brenner) have declined to comply with President Obama’s will – as expressed in the diplomatic accord (the recent ceasefire) reached with the Russian Federation.

The story is much worse than that hinted in Murphy’s title: it underlies the present mess which constitutes relations between the U.S. and Russia, and the collapse of the ceasefire.

“The FSA [the alleged “moderates” of the Free Syria Army] made for a viable partner force for the CIA on the surface, as they were anti-regime, ostensibly having the same goal as the seventh floor at Langley” [the floor of the CIA headquarters occupied by the Director and his staff] – i.e. the ousting of President Assad.

But in practice, as Murphy states bluntly: “distinguishing between the FSA and al-Nusra is impossible, because they are virtually the same organization. As early as 2013, FSA commanders were defecting with their entire units to join al-Nusra. There, they still retain the FSA monicker, but it is merely for show, to give the appearance of secularism so they can maintain access to weaponry provided by the CIA and Saudi intelligence services. The reality is that the FSA is little more than a cover for the al-Qaeda-affiliated al-Nusra. …

“The fact that the FSA simply passed American-made weaponry off to al-Nusra is also unsurprising considering that the CIA’s vetting process of militias in Syria is lacklustre, consisting of little more than running traces in old databases. These traces rely on knowing the individuals’ real names in the first place, and assume that they were even fighting-age males when the data was collected by CTC [Counterterrorism Centre] years prior.”

Sympathy for Al Qaeda

Nor, confirms Murphy, was vetting any better with the 5th Special Forces operating out of Turkey: “[It consisted of] a database check and an interview. The rebels know how to sell themselves to the Americans during such interviews, but they still let things slip occasionally. ‘I don’t understand why people don’t like al-Nusra,’ one rebel told the American soldiers. Many had sympathies with the terrorist groups such as Nusra and ISIS.”

Others simply were not fit to be soldiers. “They don’t want to be warriors. They are all cowards. That is the moderate rebel,” a Green Beret told Murphy, who adds:

“Pallets of weapons and rows of trucks delivered to Turkey for American-sponsored rebel groups simply sit and collect dust because of disputes over title authorities [i.e. Presidential authorities] and funding sources, while authorization to conduct training for the militias is turned on and off at a whim. One day they will be told to train, the next day not to, and the day after only to train senior leaders. Some Green Berets believe that this hesitation comes from the White House getting wind that most of the militia members are affiliated with Nusra and other extremist groups.” [emphasis added.]

Murphy writes: “While the games continue on, morale sinks for the Special Forces men in Turkey. Often disguised in Turkish military uniform, one of the Green Berets described his job as, ‘Sitting in the back room, drinking chai while watching the Turks train future terrorists’ …

“Among the rebels that U.S. Special Forces and Turkish Special Forces were training, ‘A good 95 percent of them were either working in terrorist organizations or were sympathetic to them,’ a Green Beret associated with the program said, adding, ‘A good majority of them admitted that they had no issues with ISIS and that their issue was with the Kurds and the Syrian regime.’”

Buried in the text is this stunning one-line conclusion: “after ISIS is defeated, the real war begins. CIA-backed FSA elements will openly become al-Nusra; while Special Forces-backed FSA elements like the New Syrian Army will fight alongside the Assad regime. Then the CIA’s militia and the Special Forces’ militia will kill each other.”

Well, that says it all: the U.S. has created a ‘monster’ which it cannot control if it wanted to (and Ashton Carter and John Brennan have no interest to “control it” — they still seek to use it).

U.S. Objectives in Syria

Professor Michael Brenner, having attended a high-level combined U.S. security and intelligence conference in Texas last week, summed up their apparent objectives in Syria, inter alia, as:

Video of the Russian SU-24 exploding in flames inside Syrian territory after it was shot down by Turkish air-to-air missiles on Nov. 24, 2015.

–Thwarting Russia in Syria.

–Ousting Assad.

–Marginalizing and weakening Iran by breaking the Shi’ite Crescent.

–Facilitating some kind of Sunni entity in Anbar and eastern Syria. How can we prevent it falling under the sway of al-Qaeda? Answer: Hope that the Turks can “domesticate” al-Nusra.

–Wear down and slowly fragment ISIS. Success on this score can cover failure on all others in domestic opinion.

Jack Murphy explains succinctly why this “monster” cannot be controlled: “In December of 2014, al-Nusra used the American-made TOW missiles to rout another anti-regime CIA proxy force called the Syrian Revolutionary Front from several bases in Idlib province. The province is now the de facto caliphate of al-Nusra.

That Nusra captured TOW missiles from the now-defunct Syrian Revolutionary Front is unsurprising, but that the same anti-tank weapons supplied to the FSA ended up in Nusra hands is even less surprising when one understands the internal dynamics of the Syrian conflict, i.e. the factional warfare between the disparate American forces, with the result that “Many [U.S. military trainers] are actively sabotaging the programs by stalling and doing nothing, knowing that the supposedly secular rebels they are expected to train are actually al-Nusra terrorists.”

How then could there ever be the separation of “moderates” from Al-Nusra – as required by the two cessations of hostilities accords (February and September 2016)? The entire Murphy narrative shows that the “moderates” and al-Nusra cannot meaningfully be distinguished from each other, let alone separated from each other, because “they are virtually the same organization.”

The Russians are right: the CIA and the Defense Department never had the intention to comply with the accord – because they could not. The Russians are also right that the U.S. has had no intention to defeat al-Nusra – as required by U.N. Security Council Resolution 2268 (2016).

So how did the U.S. get into this “Left Hand/Right Hand” mess – with the U.S. President authorizing an accord with the Russian Federation, while in parallel, his Defense Secretary was refusing to comply with it? Well, one interesting snippet in Murphy’s piece refers to “hesitations” in the militia training program thought to stem from the White House getting wind that most of the militia members were “affiliated with Nusra and other extremist groups.”

Obama’s Inklings

It sounds from this as if the White House somehow only had “inklings” of “the jihadi monster” emerging in Syria – despite that understanding being common knowledge to most on-the-ground trainers in Syria. Was this so? Did Obama truly believe that there were “moderates” who could be separated? Or, was he persuaded by someone to go along with it, in order to give a “time out” in order for the CIA to re-supply its insurgent forces (the CIA inserted 3,000 tons of weapons and munitions to the insurgents during the February 2016 ceasefire, according to IHS Janes’).

![U.S.-backed Syrian "moderate" rebels smile as they prepare to behead a 12-year-old boy (left), whose severed head is held aloft triumphantly in a later part of the video. [Screenshot from the YouTube video]](https://consortiumnews.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Screen-Shot-2016-07-21-at-12.32.20-PM-300x241.png)

U.S.-backed Syrian “moderate” rebels smile as they prepare to behead a 12-year-old boy (left), whose severed head is held aloft triumphantly in a later part of the video. [Screenshot from the YouTube video]

Support for the hypothesis that Obama may not have been fully aware of this reality comes from Yochi Dreazen and Séan Naylor (Foreign Policy’s senior staff writer on counter-terrorism and intelligence), who noted (in May 2015) that Obama himself seemed to take a shot at the CIA and other intelligence agencies in an interview in late 2014, when he said the community had collectively “underestimated” how much Syria’s chaos would spur the emergence of the Islamic State.

In the same article, Naylor charts the power of the CIA as rooted in its East Coast Ivy League power network, its primacy within the intelligence machinery, its direct access to the Oval Office and its nearly unqualified support in Congress. Naylor illustrates the CIA’s privileged position within the Establishment by quoting Hank Crumpton, who had a long CIA career before becoming the State Department’s coordinator for counterterrorism.

Crumpton told Foreign Policy that when “then-Director Tenet, declared ‘war’ on Al-Qaeda as far back as 1998, “you didn’t have the Secretary of Defense [declaring war]; you didn’t have the FBI director or anyone else in the intelligence community taking that kind of leadership role.”

Perhaps it is simply – in Obama’s prescient words – the case that “the CIA usually gets what it wants.”

Perhaps it did: Putin demonized, (and Trump tarred by association); the Sunni Al Qaeda “monster” – now too powerful to be easily defeated, but too weak to completely succeed – intended as the “albatross” hung around Russia and Iran’s neck, and damn the Europeans whose back will be broken by waves of ensuing refugees. Pity Syria.

Alastair Crooke is a former British diplomat who was a senior figure in British intelligence and in European Union diplomacy. He is the founder and director of the Conflicts Forum, which advocates for engagement between political Islam and the West.

Article published in Consortiumnews.com

https://consortiumnews.com/2016/09/29/how-the-us-armed-up-syrian-jihadists/

Geneva talks: Light in Syria’s dark tunnel?

A new round of Geneva talks started on Wednesday, with the general environment more or less positive. Increased ceasefire violations have not disrupted the peace process until now - hopefully, neither will the provocative offensives of Jabhat al-Nusra and rebel groups linked to it. However there are deep concerns over the rumors that Damascus is preparing for the offensive on the rebel stronghold of Aleppo.

A new round of Geneva talks started on Wednesday, with the general environment more or less positive. Increased ceasefire violations have not disrupted the peace process until now - hopefully, neither will the provocative offensives of Jabhat al-Nusra and rebel groups linked to it. However there are deep concerns over the rumors that Damascus is preparing for the offensive on the rebel stronghold of Aleppo.

New Syria peace talks go-between is a fixer trusted by the Kremlin

IMESClub's Council Chairman, one of the greatest world experts on the Middle East was named this week as a mediator in the Syrian peace talks and advisor to Staffan de Mistura.

IMESClub's Council Chairman, one of the greatest world experts on the Middle East was named this week as a mediator in the Syrian peace talks and advisor to Staffan de Mistura.

We share the article by Reuters on the matter.

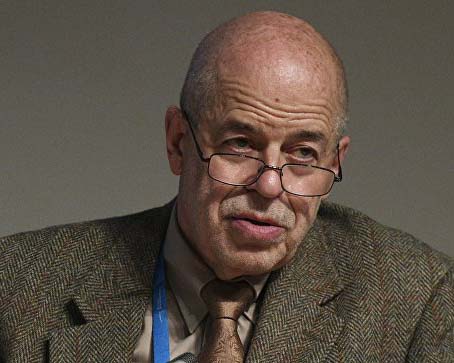

A Russian academic named this week as a mediator in the Syrian peace talks is an acclaimed expert on the Arab world with the trust of the Kremlin, a sign of the influence Moscow has won at the negotiating table after a five-month military campaign.

Staffan de Mistura, the United Nations envoy on Syria, said he had appointed Russia's Vitaly Naumkin, 70, as a new consultant to support him in brokering peace talks in Geneva between the sides in Syria's civil war. De Mistura said he also wants to appoint an American, who has yet to be named.

The posts reflect the roles of the Cold War-era superpowers as co-sponsors of peace talks that began this week in Geneva, with Moscow a leading supporter of President Bashar al-Assad and Washington friendly with many of his enemies.

Naumkin's position is likely to ensure that Moscow retains its clout at peace talks, even as President Vladimir Putin has announced he is pulling out most of his forces after an intervention that tipped the balance of power Assad's way.

Reuters spoke to nine people who know Naumkin, and all described a talented and well-connected scholar who speaks fluent Arabic and has rich experience mediating in conflicts.

He has close working relationships with Russia's leaders, and describes himself as a protege of Yevgeny Primakov, a former Russian spy chief, foreign minister and prime minister who once served as an architect of Soviet policy in the Middle East and later as an informal mentor to President Vladimir Putin.

Naumkin did not reply to a Reuters request for an interview, but acquaintances said his views were likely to reflect Russia's policies.

"He has a political line, it's our good political line," said Alexei Malashenko, a long-standing Naumkin acquaintance and scholar in residence at the Moscow Carnegie Center think tank.

TIES TO OFFICIALS

Another person who knows Naumkin, who gave an assessment of his role on condition of anonymity, described him as a talented academic who would defer to senior Russian officials on policy.

Several of the people who spoke to Reuters said Naumkin was in regular contact with Mikhail Bogdanov, Russia's deputy foreign minister and presidential Middle East envoy.

De Mistura nevertheless said Naumkin's job would be to help the U.N. mediation team, not serve Russian interests: "He reports to me, not to his own mother country."

Born in the Ural Mountains, Naumkin studied Arabic language and history at Moscow State University, before serving for two years in the Soviet army teaching Arabic to military interpreters.

He gained a reputation as an outstanding simultaneous interpreter and was called on to translate at high-level meetings between Soviet officials and Arab leaders. It was in this role that he built up a rapport with Primakov, whom he met in Cairo in the 1960s.

Primakov later invited him to work as an academic at the Institute of Oriental Studies in Moscow, according to Naumkin's own account. Naumkin did pioneering research into Socotra, an island between Yemen and Somalia, and spent periods living in Yemen and Egypt.

"He knows the Middle East not by hearsay, not from inside an office, but he's lived within it," said Alexander Knyazev, a Kazakhstan-based analyst who has known Naumkin for years.

In the early 1990s, Naumkin facilitated back-channel negotiations between rival sides in a civil war in the mainly Muslim ex-Soviet state of Tajikistan.

Naumkin arrived in the Tajik capital at the height of the fighting together with Harold Saunders, a former U.S. Assistant Secretary of State. Unsolicited, they offered their services as mediators to the Tajik leader.

When he accepted, they went to the Tajik foreign minister's house and slaughtered a sheep to celebrate, according to Kamoludin Abdullaev, a Tajik researcher who was present.

Naumkin's role in the talks was to make sure the opposition's views were heard.

"He was very assertive. The ... negotiations ended successfully," said Mars Sariyev, a former Kyrgyz diplomat who took part on the talks.

SYRIA MEDIATION

Naumkin has already played a back-room role in Syria negotiations, coordinating two rounds of talks in Moscow, backed by the Russian foreign ministry, to try to unite some of Syria's disparate opposition.

Those talks produced no major breakthrough, though not through any fault of Naumkin's, according to Nikolai Sukhov, an Arabist scholar and former student of Naumkin.

People who know Naumkin said he would be unflagging in his efforts to broker a solution in Geneva, would be on good terms with both sides and would not let emotion or frustration get in the way, even if the talks falter.

Western diplomats say it may be useful to have Naumkin in the room at the talks. One said it would encourage the Syrian government delegation to stay at the table despite its reluctance to sit down with its opponents.

Another said it could also be reassuring to the opposition, since the Kremlin has leverage over Damascus: “If the hypothesis is that the Russians will be putting pressure on the regime, maybe it is good to have this guy there.”

(Additional reporting by Olga Dzubenko in BISHKEK, Jack Stubbs and Dmitry Solovyov in MOSCOW, Olzhas Auyezov in ALMATY and Tom Miles and Suleiman Al-Khalidi in GENEVA; writing by Christian Lowe; editing by Peter Graff)

Syria: Russia is withdrawing in order to stay

Russia’s withdrawal from Syria was not a surprise to those who have been following it foreign policy. In Oct. 2015, President Vladimir Putin said: “Our goal... is to stabilize the legitimate power in Syria, and to create conditions for the search for political compromise.”

Russia’s withdrawal from Syria was not a surprise to those who have been following it foreign policy. In Oct. 2015, President Vladimir Putin said: “Our goal... is to stabilize the legitimate power in Syria, and to create conditions for the search for political compromise.”

Balance of power

Russia has returned to the Middle East and will not leave, especially since it feels that most of its regional plans are being successfully implemented.

Maria Dubovikova

US-Russian deal for Syrian ceasefire is only option that leads to de-escalation

Although Riyadh and Ankara are independent players whose interests are not always aligned with those of Washington, they will most likely support the deal promoted by the United States and Russia.

Although Riyadh and Ankara are independent players whose interests are not always aligned with those of Washington, they will most likely support the deal promoted by the United States and Russia.“This agreement is the only option for Syria that can de-escalate the conflict or at least lay the groundwork for de-escalation,” Zvyagelskaya, senior fellow at the Russian Academy of Sciences’ Institute of Oriental Studies, told Valdaiclub.comin a telephone interview Wednesday.

“The deal has demonstrated once again that Russia and the US have common political interests. Both Russia and the United States recognize that the Syrian conflict has no military solution and a political mechanism must be launched,” she pointed out.

“It is important that Moscow and Washington, as they are trying to broker a peace deal, can rely on a broad group of countries, which share their goals,” she said referring to the International Syria Support Group (ISSG).

Zvyagelskaya singled out several problems she believes will arise during the deal implementation. “First of all, it will be hard to establish who observes the deal and who does not,” she said. “It means that those parties to the conflict which are ready to cease fire must explicitly claim that,” the scholar pointed out.

Russia has played a significant role by persuading the Syrian government to start negotiating with those opposition forces, which are ready for peace, Zvyagelskaya said. “Now it is crucial that the United States uses its clout to mitigate the positions of the forces it supports,” she added.

Asked if other countries of the region, which are known to support opposition forces in Syria, could prevent implementation of the deal, the scholar said she did not expect Turkey or Saudi Arabia to disrupt the agreement. “Although Riyadh and Ankara are independent players whose interests are not always aligned with those of Washington, they will most likely support the deal promoted by the United States and Russia,” Zvyagelskaya said.

Moscow Plays Poker in Syria: What’s at Stake?

Russian military deployment in Syria should not be considered as the core goal of Moscow’s diplomacy but its instrument. It is also a serious mistake to present Russian efforts in the country as the result of a game of “chicken” between Moscow and the West. Moscow is playing a different type of game that could be characterized as “geostrategic poker”, where the Assad regime is logically considered Russia’s main stake. This stake allows the Russians to influence the situation on the ground and demonstrate their importance in the international arena by positioning Moscow as one of those players without whom the Syrian question cannot be solved. By increasing military support to the Syrian government the Russian authorities simply strengthened their stake. Now they are starting to reveal their hand.

Russian military deployment in Syria should not be considered as the core goal of Moscow’s diplomacy but its instrument. It is also a serious mistake to present Russian efforts in the country as the result of a game of “chicken” between Moscow and the West. Moscow is playing a different type of game that could be characterized as “geostrategic poker”, where the Assad regime is logically considered Russia’s main stake. This stake allows the Russians to influence the situation on the ground and demonstrate their importance in the international arena by positioning Moscow as one of those players without whom the Syrian question cannot be solved. By increasing military support to the Syrian government the Russian authorities simply strengthened their stake. Now they are starting to reveal their hand.

Misreading Moscow

Since May 2015, the West and its Middle Eastern partners have been periodically failing to read Russian intentions on Syria. First, this happened when they decided that, after playing a positive role in the settlement of the Iranian nuclear issue, Moscow would immediately help the U.S. and EU to settle the Syrian conflict. In early August 2015, Turkish President Recep Erdogan believed that his Russian counterpart Vladimir Putin already made a decision to shift support away from the official Damascus government. During summer 2015, intensive meetings between Russian, American and Saudi officials only strengthened the confidence of those analysts and policymakers who expected changes in the Kremlin’s stance on Syria. They argued that Russian withdrawal of support for Assad was a matter of time and Moscow was only trying to bargain a better deal.

Yet, in September 2015, the Russian authorities finally put an end to these speculations. In spite of all expectations the Kremlin decided to raise its stakes in the Syrian campaign: Moscow not only increased the volume of its military supplies to Damascus and improved the quality of provided equipment but launched air strikes against radical Islamists groupings fighting against the Assad regime.

As a result, by 1 October 2015, Moscow clearly demonstrated that the Russians are not going to alternate their position on Damascus. And that’s where the international community probably made a mistake for the second time: instead of trying to understand the reasons for Russian behaviour, Western media sources launched a hysterical campaign arguing that Moscow is about to send its ground forces to Syria. However, Moscow has neither abandoned Assad, nor plans to put its full-fledged army forces on the ground. This simply does not fit in with the Russian plans and the Kremlin never hid its true intentions. On 28 September 2015, during his speech at the UN General Assembly and meetings in New-York, Putin clearly stated that Russia will continue to talk to the international community on Syria but it does not mean that the military support of the Assad regime will be stopped.

Keep calm …

It is necessary to separate news about the Russian airstrikes and the rumours about Russian readiness to send significant ground troops to Syria for combat. The latter speculations should probably be taken with a grain of salt. First of all, the number of Russian advisors may indeed grow but this has a logical explanation as the volume and range of equipment supplied by Moscow to the Syrian regime raises. Consequently, more personnel are needed to train the Syrians on how to use the new equipment.

Secondly, the deployment of full-fledged ground forces for a long period and far from Russian borders would require immense economic resources. And that’s what the Kremlin lacks. Moreover, Moscow probably remembers from the Soviet war in Afghanistan (1979 – 1989) that this was one of the factors that exhausted and shattered the USSR economy; it does not want to repeat this experience.

Thirdly, the war in Afghanistan also left a psychological scar in the Russian popular mind (often compared with the Vietnam syndrome in the U.S.) that make it difficult for the Russian authorities to get popular approval for the massive use of armed forces abroad. Moscow’s experience in Ukraine should not be compared with the Syrian case: Ukraine is still considered as a part of the Russian world/space.

Finally, the limited use of force completely satisfies the Kremlin’s needs. Russia’s actual military presence in Syria definitely increases the regime’s chances for long term survival. Even Moscow’s military experts acknowledge that it would be naive to think that the Kremlin will not use its air power to help the Syrian army. It is believed that the Nusra front is probably one of the main targets of the Russian air force right now as its fighters supposedly represent the main threat to the Assad regime.

Apart from that, the current Russian presence makes any Western military intervention in Syria extremely challenging. Previously, Moscow had suspicions that the U.S.-led coalition could be used to overthrow the Assad regime. The deployment of the Russian air force in Syria allays Moscow’s concerns. At the same time, by exchanging information and trying to coordinate its military efforts with other countries Moscow continues promoting its idea of the anti-Islamic State coalition that would involve the Syrian regime, and, thus, bring Assad back from the international isolation. Russia has also strengthened its own diplomatic position by proving that any decision on Syria cannot be taken without Moscow’s participation.

Everything should go according to our plan

At the same time, the Russian ultimate goal in Syria is much more ambitious than just strengthening the Assad regime. The Kremlin remains extremely interested in the end of the Syrian war and, as it was recently re-confirmed by Putin in New-York, this settlement is only possible through the beginning of a national dialogue between the regime and the anti-government forces (excluding radical Islamists and foreign fighters groupings). However, the Kremlin would like to launch this reconciliation process on its own conditions. These conditions include the preservation of the territorial integrity of Syria, immediate formation of a united anti-Islamic State coalition, the saving of remaining state structures and the transformation of the Syrian regime only within the framework of the existing government mechanisms. Putin continues to insist on a peace settlement in Syria based around the existing Syrian state structures and institutions and with some sort of power-sharing between the Damascus regime and the “healthy” elements in the opposition.

Moscow also insists that the removal of Assad from power should not be a precondition for the beginning of the national dialogue. The Kremlin does believe that the fall of Assad’s regime or his early removal will turn Syria into another Libya. According to Moscow decision makers, this will inevitably mean the further radicalization of the Middle East and the exporting of Islamic radicalism to Russia, the Caucasus region and Central Asia. The Russian authorities genuinely believe that by helping Assad they are protecting their national security interests. In August 2014, Lavrov called the radical Islamists “the primary threat” to Russia in the region. According to Russia, Assed is the only person able to guarantee the integrity of the Syrian state and the military institutions needed to fight against Daesh/IS and other radical Islamists. Although Moscow does not exclude that Assad could be replaced in the future, it should happen no earlier than when there is confidence in any new leaders who are able to control the situation in Syria.

This vision of the situation drastically differs from that of the West and many Middle Eastern powers that consider Assad as the source of the Syrian problem rather than its solution. Yet, the Kremlin is determined to change the international opinion. Presumably, the Russian authorities adopted a two track approach. On the one hand, since the spring 2015, the Russian authorities intensified their dialogue with the international community. This step made some policymakers mistakenly think that Moscow was looking for ways to trade Assad for some economic and political concessions. Meanwhile, the main task of the Kremlin was to impose its views on the conflict settlement. On the other hand, the Russians increased the volume and quality of military supplies as well as launched the military operation in the country to guarantee that the Syrian regime will make it long enough to see the moment than the Kremlin achieves the break through on the diplomatic track.

It works

So far, the Russian plan works. The Syrian regime will stay in power for some time. Meanwhile, the Russian idea to establish an anti-Islamic State coalition with an active role for the Syrian regime, and, thus, brings back Bashar Assad from the international isolation, is gradually finding support outside of Russia. Thus, during his August trip to Moscow, Egyptian president Abdel Fattah al-Sisi expressed support to the Russian initiative. Some western politicians also started to express their ideas that the West probably should deal with Damascus to succeed in its anti-IS struggle.

All of this, in turn, makes Moscow believe that it has chosen the right strategy. Consequently, any attempts to convince the Russians not to increase military support for Damascus or change their stance on the conflict will be challenging. Under these circumstances, it makes sense to ask whether the international community should deal with Russia on Syria?

It not only should, but probably has to continue the dialogue with the Russians. First of all, Moscow does not want to escalate confrontation with the West over Syria beyond the current level. Moreover, the Russian authorities are doing their best to clarify their position. Thus, on 15 September 2015, during the Collective Security Treaty Organisation (CSTO) summit in Dushanbe, Putin unexpectedly devoted most of his speech to the Syrian issue. His presentation was balanced, devoid of any anti-American rhetoric and definitely addressed to the West, as this topic lies far beyond the interests of the other CSTO members. Putin stressed that the real goal is a peace settlement in Syria.

The Russian vision of the future of Syria is also changing. Recent statements made by Putin and Lavrov in September show that Moscow has finally stopped labelling all fighting opposition forces as “terrorist” and recognized at least some of them as legitimate players. Previously, Moscow agreed to deal only with the political wing of the Syrian (preferably, official) opposition. I t is still unclear who those military forces are that Moscow now wants to include in the national reconciliation process and the building of anti-IS coalition. It definitely plans to build relations with the Syrian Kurds but also with those whom Putin vaguely determined as “healthy” opposition. On 9 and 13 September 2015, the Russian MFA clarified this definition by stating Moscow’s readiness to include into the anti-IS coalition the Syrian moderate opposition and those Syrians who are not foreign fighters or international jihadists. Theoretically, this statement allows for the legitimisation in Moscow’s eyes of those moderate Islamists whohave serious influence on the ground but whoRussia previously avoided dealing with. Finally, in the early October 2015, the Russian MFA openly declared Moscow readiness to negotiate with the Free Syrian Army.

In September 2015, Russian officials also became more certain about the possibility of political reforms in the country and views about a post-Assad Syria. Until now, the Russian authorities have considered Assad the only person capable ofguaranteeing the integrity of the remnants of the state and military institutions which survived the previous years of conflict and are still capable offighting against Daesh/IS. Yet, Moscow does not exclude that he could be replaced in the future. However, this should not happen before there is confidence that the new leaders are able to control the situation in Syria. Ultimately, Moscow sees the gradual transformation of the regime as inevitable and has raisedthe possibility of conducting early parliamentary elections.

Keep on playing

Moscow has few doubts, so far, that it has chosen the right strategy. In view of this, any attempts to browbeat Moscow into stopping its military build-up in Syria, not to speak of changing its longstanding stance on the conflict are a waste of time. The Kremlin has carefully stage-managed this entire effort that turned its military presence in Syria into a new regional factor. Moscow is still determined to change the international position on Syria’s future via a two-track approach. Yet, what the Kremlin is going to get at the end is not necessary completely contrary toWestern interests: Moscow accepts the idea of the post Assad Syria and simply wants to guarantee the Russian presence in it.

Initially published: http://trendinstitution.org/?p=1496

Russia in Syria: Obscure Solutions to Obscure Challenges, and the Risks Surrounding them

Pursuing an active policy in Syria up to direct involvement in the military conflict seems to be bringing Moscow both fresh opportunities and new risks, both internal and external, that range from the palpable to the obscure.

Pursuing an active policy in Syria up to direct involvement in the military conflict seems to be bringing Moscow both fresh opportunities and new risks, both internal and external, that range from the palpable to the obscure.

Risks

The most obvious risks are image-related. While the denigration of Russia in Western media has become routine in recent years, the perception of Russia in the Arab and Islamic information field has always been more nuanced. While some TV channels (Al-Arabia, Al-Jazeera and the Gulf media) have vilified the Kremlin for supporting Bashar Assad, others such as Shiite TV station Al-Manar, Egyptian newspaper Al-Ahram, etc., have been openly supportive about Russian anti-Americanism.

But now the situation has changed.

Under certain circumstances, the Syrian operation may help Russia in its relations with the West, but information-wise the status quo is likely to remain for a long time to come. As a result, some will see Russia as a country that defends dictators and bombs the moderate opposition and civilians, while others will see it as an enemy of the Sunnis. Details regarding the groups bombed, real targets for air attacks, or the fact that Russia has 20 million Sunnis residing in its territory will be virtually ignored.

The most obvious risks are image-related.

Russia is, as always, rather weak in information warfare, and apparent absurdities like the total defeat of ISIS in areas controlled by the Free Syrian Army [1] voiced by official sources only serve to aggravate the situation. The Arab community, including Christians, rejects Russian commentators’ attempts to interpret the Syrian campaign in religious terms as a holy war, the Russian Orthodox Church’s religious mission, etc. Such statements not only revive the image of Western crusades in the Middle East but also echo with the offensive missionary rhetoric of George Bush Jr.

Russian domestic propaganda correlates poorly with foreign media outreach, and a comparison of the two information streams gives the impression that Moscow's policy is neither consistent nor transparent.

However, these image-related losses are far from being the biggest problem, as the looming political risks are much more ominous.

The three main domestic risks have been much talked about and boil down to possible popular discontent over the Kremlin's policies.

First there is the terrorist threat, which seems to have firm foundation. On the one hand, there are ISIS sympathizers resident in Russia who see the Syria operation as an assault on genuine Islam. The other involves thousands of battle-hardened and well-networked Jihadis who will be driven out of Syria first to Iraq and then to their homelands, which seems to be exactly the scenario Moscow is trying to prevent by interfering in the Syrian affairs.

The logic of ISIS’s evolution has prompted the inevitable gradual ouster of romantic jihadis out of their current territory and the future export of jihad. Southern Russia is definitely high in their priorities list. Hence, President Putin's approach "strike first if the fight is unavoidable" seems to perfectly match this logic.

First there is the terrorist threat.

Risk number two involves the unpredictable response of Russian society to any future battlefield losses. When ISIS captured a Jordanian pilot and burnt him in a metal cage, thousands of people in Amman went out onto the streets to protest both against ISIS and the participation of Jordanians in the war on the Islamists. There has been no similar trigger-event reported involving Russians, and any similar public response by Russians has yet to be seen, not least since Moscow's previous military campaigns in the southern Russia left a negative impression Russian public consciousness.

Risk number two involves the unpredictable response of Russian society to any future battlefield losses.

At the same time, it is no secret that weakening of traditional bonds combined with the underdevelopment of liberal values and civil society have atomized Russian society, undermining its ability to mobilize and increasing its tolerance regarding human victims.

Finally, the third domestic risk involves economic impact of the Syrian campaign. Irrespective of the burden on the Russian state budget (which is not thought to be enormous, in terms of purely military costs), given the broader economic downturn, the general public will find it hard to understand the need for yet another round of belt tightening, this time for the sake of murky geopolitical interests in a faraway and essentially unknown country.

The likelihood of this risk becoming a real concern will grow with time. If the operation lasts several months and produces striking political effect, the population is unlikely to launch serious protests.

All these obvious risks only prove that the Syrian operation must be swift and bring political resolution acceptable both for the Arab world and the West. Only in then would Russia's reputational losses be more or less compensated and its claims for leadership justified.

The third domestic risk involves economic impact of the Syrian campaign.

This prompts us to look at the issues that Russia needs to resolve in Syria.

Obvious and not so Obvious Issues

All these obvious risks only prove that the Syrian operation must be swift and bring political.

What Moscow requires is the establishment of a relatively friendly Syrian regime to guarantee continued Russian military presence there. This scenario may indicate Russia’s real return to the region and its ability to effectively resolve large-scale problems beyond its near abroad, as well as its claim to the role of Europe's shield, which could radically alter the entire relationship with the EU on Russian terms.

The need to solve this triple conundrum, i.e. a swift operation, a settlement recognized globally and regionally, and the establishment of a stable regime, brings to the fore the problem of political resolution according to a scenario that should determine the military operation.

What Moscow requires is the establishment of a relatively friendly Syrian regime to guarantee continued Russian military presence.

The official aims proclaim counterterrorism and support of statehood, which allow for very broad interpretation, as terrorism may apply both to ISIS and the armed opposition, and statehood support – to strengthening the incumbent president or the preservation of Syria on the world map.

In fact, looking at these political issues opens the way to analyze the aims in greater detail.

Russia will not be pleased either with an excessively broad or excessively narrow interpretation of the term terrorism, because the former would boil down to a mere strengthening of the ruling Syrian regime (unacceptable to the international community and Middle East), and the latter would deprive Damascus of any motivation to participate in the resolution, effectively taking us back to the situation that existed two years ago. Hence, the problem is in drawing a red line dividing the opposition into moderate and radical segments, and further engaging the moderates in the settlement process.

In most cases, it is hardly plausible to rate the opposition's radicalism by religion or commitment to violence or by political agenda. In the final count, the religious discourse is employed by too many sides of the conflict, this civil war has already claimed over 200,000 lives, the level of violence is already excessive, and political agendas of many parties involves have nothing to do with reality.

Methodologically, it would seem more sensible to single out ambitious structures orientated at nation-building, comprising Syrians and trusted by some elements in the Syrian population. Such groups may be quite small but still emerge as constructive actors in the peace process despite ideology and other factors.

As far as statehood is concerned, the formation of a relatively stable political system implies the need for this military operation to be accompanied by other activities aimed at strengthening institutions and the country’s reintegration.

Elites in Russia and other countries plus the expert community have been criticizing the U.S. intervention in Iraq for 12 years. The invasion should clearly have been avoided, with all the attendant gross errors, the ensuing protracted crisis and terrible violence that has taken almost 200,000 lives. However, the United States attempted to provide Iraq with a new political system and preserved statehood, suffering enormous financial, image-related and human losses.

Russia will not be pleased either with an excessively broad or excessively narrow interpretation of the term terrorism, because the former would boil down to a mere strengthening of the ruling Syrian regime and the latter would deprive Damascus of any motivation to participate in the resolution.

For five years, the West has been censured for its Libyan operation that differed from Iraq in its limited dimensions and was limited to air support of anti-Qaddafi forces. Given the Iraq experience, neither Europe nor the United States were ready to take responsibility again. But the Libyan state fell apart.

Neither scenario would suit Russia.

The rapid completion of the operation and restored statehood would offer a small or very small Syria, with the government bolstered by Russia within a limited territory, e.g. in Latakia and Damascus. At the same time, President Putin's remark at the Valdai Forum that forgetting the country’s previous borders would entail the emergence of several permanently warring states is also quite true. The only way out seems to lie in some kind of decentralization of Syria and the division of responsibility for its territory among other powers, primarily regional countries that could help Syria strengthen institutions in its interior areas.

The rapid completion of the operation and restored statehood would offer a small or very small Syria.

Finally, the restoration of statehood would require massive assistance to overcome the economic consequences of the war, which primarily involves financial aid (USD 150-200 billion over a period of 10 years by ESCWA estimates), as well as establishment of bodies for the distribution of funds and control over spending.

Certainly, neither Russia nor any other country would be able to do this on its own.

As a result, all these goals, i.e. turning the moderate opposition into the government's partner, reintegration of the Syria territory, and economic revival, necessitate a reformatting of the approach to external participation in the Syria settlement on Russian terms, and the identification of partners able to operate within the boundaries set out by Moscow.

With due respect to the Western role in the Syrian settlement and the significance of Russia-West relations, the key partners should come from the region.

First, the West is the potential target audience of Russia's efforts in the Middle East and has to show it has received the message about Russia's return to the regional theater. Russia is working to alter the format of its relations with the West and to display its readiness to be a global power.

Second, although Russia's relations with certain Middle Eastern states are hardly healthy, they are free of the kind of burdens seen in Russia-West dialogue. Cooperation on Syria with the West will always remain a sort of projection of the entire bilateral relationship.

Third, it is the countries in the region that are most interested in Syrian normalization and the restoration of order to this territory swamped in chaos.

As for the search for regional partners, until recently Russia's Middle East strategy was described by Western analysts as "the art of being everybody's friend." But things are different now. By supporting the Syrian government and establishing an information center in Baghdad, Russia has effectively built a Shiite coalition in a Sunni-dominated region dominated.

All these necessitate a reformatting of the approach to external participation in the Syria settlement on Russian terms, and the identification of partners able to operate within the boundaries set out by Moscow.

The Russia-Iran rapprochement hardly seems a guarantee for a long-term alliance. With the military operation completed and the settlement process launched, the two powers would naturally become rivals competing for influence in Syria, while Iran, exhausted by its pariah state status, is likely to choose the pro-Western track.

Tehran is too close to Damascus and is short of resources, which would seriously limit its ability to influence the solution of these three problems.

To this end, Russia should be especially interested in engaging the Sunni states, i.e. Turkey and Saudi Arabia, countries that have become estranged from Russia because of its Syrian operation.

Relationship normalization requires a degree of accommodation of their interests. Turkey needs to see the Kurdish threat minimized, and Saudi Arabia would like to check the rise of the Shiite belt. Theoretically, and both problems could be handled (to a lesser extent that involving the Kurds) within the process of Syria's political transformation and its territorial reintegration.

With due respect to the Western role in the Syrian settlement and the significance of Russia-West relations, the key partners should come from the region.

Besides, Moscow could offer Riyadh diplomatic assistance in the Yemen settlement, as the military operation there appears undeniably flawed.

Concurrently, Russia could also exploit the grave differences that exist between the Sunni states.

Although Egypt is dependent on Saudi Arabia, it views their relationship as rather burdensome and would be glad to see Russia as an alternative partner. The creation of a counterbalance to the Shiite alliance in the Moscow-Cairo-Algiers axis for stabilizing North Africa would help Egypt gain regional clout, while Russia would demonstrate its refusal to take part in the region's confessional confrontations.

Besides, minor Gulf states will not always support the Saudis' anti-Iran policy, whereas Turkey views Russia as a key economic partner.

By supporting the Syrian government and establishing an information center in Baghdad, Russia has effectively built a Shiite coalition in a Sunni-dominated region dominated.

Finally, Moscow could boost its efforts in the Palestine settlement by lending momentum to the intra-Palestinian political process and taking practical steps to strengthen state institutions of the Palestine Authority, thus demonstrating its constructive role in the region.

In theory, all these measures coupled with the Russia-Iran partnership and effective cooperation with Israel could spawn conditions amenable not only to a Syrian settlement but also to building a new stable system of regional relations in the Middle East. However, the requirements for a healthy outcome are so numerous that an optimistic future appears essentially indistinct.

INITIALLY WAS PUBLISHED ON RIAC: http://russiancouncil.ru/en/inner/?id_4=6789#top-content

Alternative Visions of Syria’s Future: Russian and Iranian Proposals for National Resolution.

Alternative Visions of Syria’s Future:

Russian and Iranian Proposals for National Resolution

(Presented at the European Parliament on November 12, 2015)

First of all, I would like to thank you for inviting me to speak here today. There are many conflicting views regarding Russian involvement in the Syrian conflict and the degree to which Russia and Iran are coordinating their actions there, with many misunderstandings on all sides. It is indeed a topic that needs to be discussed. I will divide this brief overview into three parts:

- Russian goals in Syria

- Iranian goals in Syria

- The nature of Russian-Iranian coordination in Syria.

Russia

Russia’s immediate goal, in simplest terms, is to end the fighting and return stability to Syria. The Kremlin has made it clear that: it considers president Assad’s government legitimate; considers Russian intervention legal because made at the request of the Assad government; and — importantly — that it does not consider extremist elements limited to IS but that they are fluid groups of fighters operating under different banners often receiving financing and training under the guise of moderate opposition and then bringing those resources to IS, the Al-Nusra Front, Al Qaeda and any number of other radical military forces. This does not mean that Russia is not willing to engage genuine moderate Syrian opposition. As a matter of fact, Russia has been engaging the Syrian opposition, whose representatives — along with those of the Syrian government — have come to Moscow for talks time and again throughout the civil war. I myself have met with them. Russia has also engaged the moderate Syrian opposition in the Geneva conferences and other international talks.

Once peace has been reestablished, work can begin on strengthening and rebuilding Syria’s state institutions. Russia supports the communiqué issued by the Geneva I conference on Syria, calling for “a transitional government body with full executive powers.” This transitional government should be secular and inclusive of all different segments of the Syrian population.

The next step would be democratic elections. The oft-repeated claim that Russia is insisting on an Assad-led Syria for all time contradicts official statements by Russian diplomats and the Russian president. The Russian position is that changes and amendments in the Syrian government and governmental institutions should be effected through democratic processes, not violence, and by the Syrian people (even including some members of violent opposition, whose voices should also be heard, on the condition that they abandon violence). Foreign intervention is needed not to handpick a new (or artificially enforce an old) government for Syria, but to provide the stability and peaceful conditions necessary for real democratic processes.

In addition to the defeat of radical religious fighting forces, the territorial integrity of Syria must be preserved. Moscow is against the “balkanization” of Syria, which would only result in a collection of weak countries divided along ethnic, confessional or political lines and all the more likely to fight among one another in the future.

Another important strategic point is that any attempt at resolution must address the region as a whole: regional players, such as Iran and Saudi Arabia, must be involved; the government of Iraq must also be strengthened, as well as the government of Libya, whence many fighters are reportedly arriving into Syria. Ideally, an even broader international coalition would engage these challenges, something Moscow would only welcome.

In any case, the current situation in Syria cannot continue. The four-plus years of civil war, and around 250,000 dead and 11.5 million overall refugees, has been accompanied by unfortunate actions on all sides but at least partially inflamed by ill-advised and poorly controlled US-funding and support of opposition groups as well as underground money and arms from other sources.

The goal of stability and resolution in Syria is all the more urgent for Russia because increasing numbers of Russian citizens and citizens of neighboring states are traveling to the Syrian battlefield, often from the Caucasus and Central Asia. In mid-2015, the Russian Federal Security Service (FSB) set the figure of Russian citizens fighting alongside opposition groups in Syria at approximately 1,800. Naturally, it is difficult to obtain hard numbers, but observers in the Institute for Oriental Studies in Moscow more recently cited a larger figure of around 4,000 fighters from the Russian Federation, and 7,000 from the former Soviet Union. These figures have increased alarmingly since the first years of the civil war in Syria. And the problem is not merely radicalized Russian citizens: a huge number of Central Asians find employment in Russia, especially in the Russian capital, crossing the Russian border without requiring a visa. In that sense, post-Soviet territory resembles the European Union and faces many of the same dangers from returning fighters moving with relative freedom among countries within the territory. Iranian sources are claiming that there are 7,000 fighters from Central Asia alone in Syria and that that around 20% of Islamic State commanders hail from Central Asia.

A Tajikistan government source has been quoted as saying that around 300 Tajik fighters have been killed in Syria and Iraq, and 200 remain there. According to the same source, the parents of 20 fighters recently approached the Tajikistan government for help in returning their sons stranded near the Syria-Turkish border.

It is common knowledge that websites exist for recruiting fighters in Russian and other languages of the former Soviet republics of Central Asia. Russian social networking sites such as “V-kontakte” and “Odnoklassniki” also carried content and calls to arms, until those accounts were recently shut down. Other sites, such as “Telegram” have proven more difficult to control Recruitment techniques vary from pure ideology to money. A common theme in these messages is the reestablishment of the caliphate.

Very recently, however, many Russian-language insurgent sites and blogs have simply gone silent of their own accord. It is difficult to say whether this is due to the accuracy of the Russian airstrikes or greater caution by the fighters – who, in at least one instance, accidentally revealed their location: in April, the Chechen-led “Al-Aqsa” brigade in Syria posted a photograph of a training camp in Al-Raqqa, Syria, but forgot to deactivate the “location finder” on a the Russian social networking site “V-kontakte.” Government sources in Tajikistan consider the Internet silence to be the result both of increased fatalities among Tajik fighters and increased disillusionment and desertion.

Iran

Now let us talk about Iran’s interests in Syria. Media and experts have commented much on the importance of Bashar Assad’s government as an ally to Iran, and Syria as a bridge to Hezbollah in Lebanon and as a buffer zone between Iran and Israel. This is true, and yet it is no less true that the current chaotic violence in neighboring Syria could be devastating to Iran were it to spread further. It should also be remembered that Iran and Syria have signed a mutual defense treaty, each promising to intervene on the other’s behalf in case of outside aggression from a third party.

As far Iranian proposals for resolving the conflict, Fars news agency published a four-point plan for Syria from a high-ranking Iranian government source. Parts of this plan have been echoed by other Iranian officials, and it coincides roughly with the Russian proposals, although the Iranians emphasize the need to revise the Syrian constitution and end foreign intervention as soon as hostilities have ended. The plan is

1. Immediate cessation of hostilities.

2. The formation of a federal government in which the interests of all segments of the Syrian population are represented, i.e., religious and ethnic groups.

3. Revising the Syrian constitution to protect and provide representation for the different ethnicities and confessions that comprise the Syrian population. I have heard this referred to as “Lebanization,” since Lebanon’s constitution offers similar guarantees to the different groups that make up its varied population; but it should be noted that the Iranian constitution itself also offers protection and parliamentary seats to ethno-religious minorities.

4. Any new leadership and changes to government institutions must be realized through elections with the participation of international observers.

According to the source, this plan is currently being reviewed by Turkey, Qatar, Egypt and UN Security Council members.

Speaking in Sochi, Russia, in October of this year at the “Valdai Discussion Club,” Iranian Parliamentary Speaker Ali Larijani, outlined his country’s perspective on the conflict in Syria, a perspective that, again, shares much with the views expressed by President Putin and Foreign Secretary Sergei Lavrov: the problems in Syria are part of a regional collapse in security that will require the efforts of all regional players to correct. A strong and stable Syria will be unlikely with chaos next door in Iraq, or even in Afghanistan. Two points that Iranian and Russian officials have both emphasized are that the Syrian people must choose their own government and that the territorial integrity of Syria must be preserved.

Coordination between Russia and Iran

During negotiations over Iran’s nuclear program, many Russian commentators questioned the wisdom of Russia’s support for a deal between Iran and the P5+1. Would a stronger Iran turn its back on Russia? Would Iranian oil flood the market and hurt the Russian economy? In other words: what was “in it” for Russia? Perhaps now, in the joint Iranian-Russian efforts in Syria we are seeing that the two countries had more developed plans for working together than was presumed.

Amir Abdollahian, Iranian Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs and Counselor on Arab and African States, stated this month that Iran is only providing consultative and informational support to Russia, while actual military operations are being carried out by the Syrian government and Russian armies (there have been rumors of deeper Iranian involvement, however, that Iran is preparing to send 7,000 troops to Syria). Additionally, Russia, Iran, Syria and Iraq have created a shared intelligence base to battle terrorism in the region, and Russian missiles launched from the Caspian Sea cross Iranian airspace on their path to targets in Syria. In a move not directly related to Syria but indicative of closer ties, Russia is again preparing to sell S-300 anti-aircraft installations to Iran.

Russia has also provided diplomatic support for Iran, as Moscow considers achieving peace in the region an impossible dream without the participation of Iran. The Kremlin has consistently lobbied for Iran’s inclusion in the Geneva and other talks on resolving the Syrian conflict.

Iran, for its part, has enthusiastically supported the Russian aerial offensive. House speaker Ali Larijani praised the Russian campaign in Syria as being highly effective. When US sources claimed that Russian missiles malfunctioned and crashed in Iran on their way to Syria, the official Iranian press rallied to Russia’s defense, denying the claim and branding it as part of an information war against Russia.

Nonetheless, the Russo-Iranian alliance is not seamless and should perhaps better be called a partnership for now. At times, these differences even escalate into competition. Let me mention a few points worth remembering about these partners in Syria. Iran is a religious state, and thus takes confessional issues into account in its foreign policy – namely, the fate of Syrian Shia minority. Russia is a secular state. While the fates of Christian communities in Syria are certainly an important factor for Russia, the driving calculus of the Kremlin is secular.

Although Iran is often characterized as a vertical power structure devoid of dissent, the Syrian question is nonetheless a focal point of disagreement between the reformist and conservative camps, with debate over the degree to which Iran’s military should be involved in Syria and the wisdom of footing the bill for such intervention and providing financial support for Assad’s government. The coordination with Russia is viewed differently within Iran: how close should or can the Russo-Iranian alliance be? Many see Russia as a fair-weather friend. Russian delays in the construction of Iran’s nuclear power plant in Bushehr and the backing out of a deal to sell Iran S-300 anti-aircraft installations are in Iran widely believed to have been due to pressure from the United States and/or Israel, perhaps in a exchange for Russian WTO membership. What’s more, on a cultural and historical level, the wars and territory Iran lost to Russia in the last centuries of the Russian Empire still loom large in the Iranian consciousness.

One reported fissure in the Russian-Iranian coordination in Syria concerns the question of President Assad’s role in the future of the country. Russian Minister of Foreign Affairs Sergei Lavrov’s recent indication that Assad’s future presence would not be essential for Russia drew criticism from the head of the Iranian Revolutionary Guards, who apparently said Russia was acting in its own interests, implying it had abandoned an earlier agreement with Iran. This was quickly downplayed, however, in subsequent official statements by the Iranian government.

The incident looks probable enough at first glance, but would seem to contradict the basic principles both Russia and Iran have set forth for Syria: that the people of Syria must come to a consensus regarding their government via elections, the results of which might or might not include Bashar Assad. One wonders, then, what the Iranian commander’s words really were and whether they represented a real split. It is often difficult to discern when disagreements between factions in Iran are real or staged. Theoretically, all statements by the Iranian president and other high-ranking officials have the approval of Ayatollah Khamenei, who is thought often to send contradictory messages through different channels, either to appeal to different audiences (domestic and foreign) or perhaps to muddy the waters as to the country’s real intentions.

At the end of his October speech at the “Valdi Discussion Club” in Russia, Larijani emphasized the difficulty of the task ahead in Syria, of defeating terrorism in the region and the need to prepare for a long-term struggle. His words were certainly addressed to his Russian counterparts, in addition to others: “The biggest question is whether this new lineup of forces, which must be lasting, can be created without a theory of strategic coalition?” I read this as Larijani asking: Is the partnership forming between Russia and Iran one of temporary convenience or something more? As the two countries cannot be said to be united by state ideology, is it possible to construct a larger strategy or framework for their partnership?

Larijani continued:

The fight against terrorism cannot be considered a tactical and short-term project. We will need to work hard and long to create a new security system in the region […] We need to develop long-term strategic ties […] including […] cultural, political, economic and security relations to help responsible countries develop trust for each other and to start strengthening this trust.

Russia’s consistent diplomatic support of Iran in recent years and statements like Larijani’s above seem to indicate that both countries are taking a potential alliance more seriously now, despite efforts to drive a wedge between them. Such an alliance, especially if part of a larger coalition and if truly used to promote stability and empower the peoples of the region, could be a powerful force for positive change in a region that, alas, has benefitted little in past decades from Western intervention.

Despite airstrikes, is Russia still working toward political solution in Syria?

In recent days, it has become apparent that Russia, while continuing its air campaign against the Islamic State (IS) and Jabhat al-Nusra positions in Syria, is paying attention to the search for a political solution to the Syrian crisis. Some analysts even argue that Moscow is beginning to lean toward "the idea that a political solution for the region would include a post-Assad Syria," as Nikolay Kozhanov from Carnegie Moscow Center wrote regarding Syrian President Bashar al-Assad.

In recent days, it has become apparent that Russia, while continuing its air campaign against the Islamic State (IS) and Jabhat al-Nusra positions in Syria, is paying attention to the search for a political solution to the Syrian crisis. Some analysts even argue that Moscow is beginning to lean toward "the idea that a political solution for the region would include a post-Assad Syria," as Nikolay Kozhanov from Carnegie Moscow Center wrote regarding Syrian President Bashar al-Assad.

Russia sincerely believes what it is doing serves the interests not only of Shiites and non-Muslim minorities in the Middle East, but the whole Islamic world, including the Sunni majority — to which 20 million Russian Muslims belong. Over the years, in various parts of the North Caucasus and the Volga region, the victims of these terrorists who are trying to brainwash Muslims have been ordinary believers, imams, muftis and prominent theologians. The number of young Muslims duped via the Internet and recruited to join IS has already crossed the "red line."

It appears Moscow didn’t expect Riyadh to react so negatively to the Russian military campaign against the jihadis in Syria, considering they threaten the security of the kingdom no less than Russia’s. After all, the Saudi regime has always been one of the main targets of these Islamic radicals. Close cooperation with Iran, however, without which it would have been impossible to conduct the military campaign effectively, has been like a red cape to a bull for the Saudi establishment, especially the religious one, which is lashing out at Moscow. Still, one can hear voices of support among the Saudi public for Moscow’s actions to weaken one of the kingdom’s enemies, namely IS.

However, there are those who believe Russian airstrikes only increase the flow of militants to the ranks of the radicals. Russia is actively challenging this view. It is important to Moscow to explain Russian aims, especially to the Sunni majority of the Muslim world, and prevent the incitement of anti-Russian sentiment by the extremists, who capitalize on Sunni solidarity. Unlike its allies in the "Baghdad coalition," especially Iran, Russia cannot be suspected of pursuing religious objectives, and this works in its favor. The Kremlin doesn’t want to interfere in any way in any intra-Muslim showdown, especially since Russia's population includes a Muslim community whose members are all adherents of the Hanafi and Shafi’i schools of thought.

Moreover, Russia didn’t and doesn’t have any ambition to "dominate" in Damascus, which is evident in Assad’s intransigence with Moscow on issues related to negotiations with the opposition. In Spiegel Online, Christoph Reuter even argues that Assad asked Russia for help to contain the Iranians, putting himself in a position "to play off his two protective powers against each other." However, doesn’t this sound a little bit too sophisticated?

Still, accusations that Moscow is religiously biased, especially coming from some Arab capitals, continue unabated. The ongoing information war is fierce and resorts to grotesque falsification. Writing in the newspaper Asharq Al-Awsat, Riyad as-Seyyid put forward a thesis about the four "foreign-led holy wars against Arabs," combining "Jewish Zionist colonizers," "Iranian adherents to Shiite proselytism," IS jihadis and Russian Orthodoxy.

According to his theory, crusades have supposedly been organized by Byzantium (sic!), while the Russian Orthodox Church has called Russian President Vladimir Putin’s actions in Syria a "holy war" (naturally, this isn't the same as Byzantium’s campaigns). Russian military officials would be very surprised to hear they are conducting some kind of religious war. They know they haven’t been sent to war, but to a time-limited air campaign against a dangerous enemy that threatens the security of their country. They aren’t really concerned about the Sunni-Shiite divide.

As for Israel, while the vast majority of Russians strongly disapprove of Israel’s policies toward the Palestinians — whom Russia has always supported — they nonetheless appreciate the Israeli government for its neutrality in the Syrian crisis and Russia's actions in the region. From their side, Russian officials have guaranteed Israel that no violence against the Jewish state will come out of the Syrian territory where Russia and its allies operate.

At the same time, as written in a Jerusalem Post editorial Oct. 9, "Israel must be careful not to be seen to be working with Moscow against the Syrian opposition." Anyway, Moscow doesn’t intend to work against all Syrian opposition, least of all in collaboration with Israel. Moscow doesn’t need anything from Israel but neutrality in Syria, though Russian analysts monitor the views expressed in the Israeli media. Here, journalist Amotz Asa-El’s opinion is instructive: "If indeed Russia emerges as post-war Syria's political sponsor, it might keep a lid over Israel's northern enemies."